(In)Fertility

the inability to get pregnant after one year of regular unprotected intercourseCFReSHC CF-SRH Resource Guide by Patients for Providers and Patients

Key

For Providers

For Patients

For Patients and Providers

Introduction

Infertility is a condition with which many women with CF struggle. However, not all women with CF are infertile, although this is a common misconception. [see the Contraception chapter]. Further, not all women with CF want to conceive or have a child [see the Family Building chapter]. We have designed this chapter to specifically help providers and patients gain an understanding of the basics of fertility evaluation and infertility treatment.

- Do you have any questions or concerns about fertility or infertility?

- Do you think you will ever want to get pregnant?

- Do you want to get pregnant in the next year?

*Recommendations:

- Refer the patient who expresses a desire to become pregnant to a maternal fetal medicine practitioner (ideally one who understands CF) for a preconception consultation.

- Have information readily available to patients regarding fertility, as well as OB/GYNs and Reproductive Endocrinologists that you would recommend to your patients.

- For females with CFRD: Can you let me know if/when you are considering pregnancy so that I can prepare to make necessary treatment changes? Fertility treatments and pregnancy may require me to make changes to your medical management plan.

To a CF provider:

- Do you think I am healthy enough to undergo fertility treatments and/or safely carry a pregnancy?

- Do you have any recommendations and/or referrals to high-risk OB/GYN, reproductive endocrinologist, or maternal fetal medicine provider in the area?

To a Reproductive Endocrinologist:

- Do you consider different treatment protocols for women with CF? What are they?

- Have you ever treated a patient with CF before? If so, how did that go?

- How often would you like to be in touch with my CF team? How can I help facilitate any necessary communication with my CF team?

Infertility’s Impact on Women’s Lives

Many women express the desire to procreate. Those with CF are no exception. However, some women might find that embarking on that journey might be a little bit more complicated. For women with or without CF, infertility can be unsettling. As with any significant loss, individuals who learn they are infertile often experience a range of emotions, including shock, grief, depression, anger, frustration, a loss of self-esteem or self-confidence, and a sense of having no control over one’s destiny [1].

Adding to this picture, however, is that patients with CF are 2-3 times more likely than the general population to report depression and anxiety, with or without infertility; a subset of this group experiences anxiety specific to medical procedures [2]. Fertility treatment adds new high-stakes, medical procedures and encounters for patients with CF. When females with CF undergo fertility treatment, there is the added burden of additional doctor’s appointments, blood draws, and invasive testing. Appointments are usually first thing in the early morning so that medications can be tweaked for the day, if needed. These early appointments mean that women with CF may face additional pressures to get their treatments done early, eat breakfast, take medications, and get out the door to get to the fertility clinic on time. A patient’s ability to adhere to CF medical regimens may be compromised while undergoing fertility treatments; CF providers should acknowledge and support their patients to maximize their ability to fulfill their CF treatments.

Existing Research

Possible Causes of Infertility in Women with CF

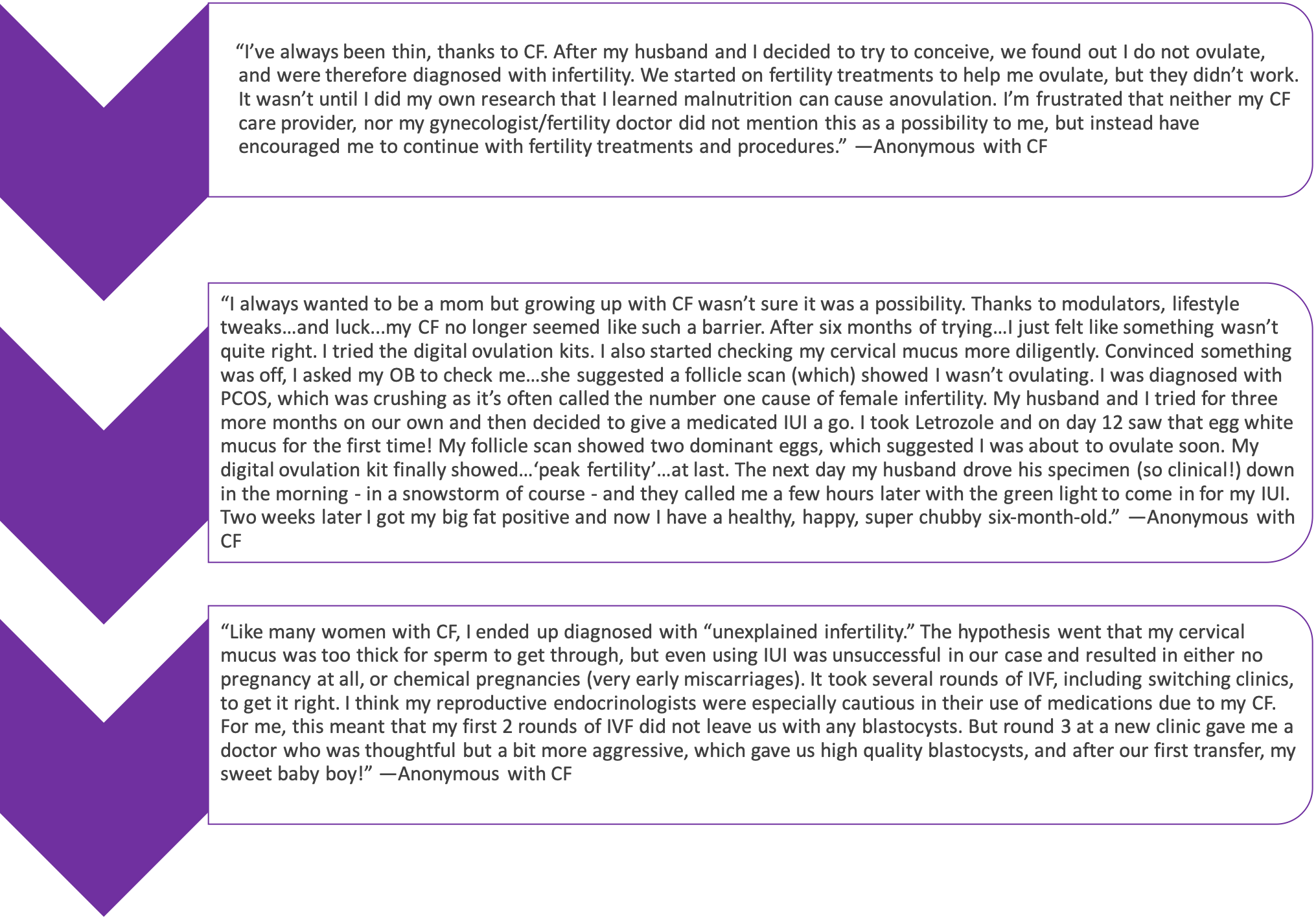

In the 1980s, researchers indicated that girls with CF reached menarche later than those without CF and had higher rates of irregular menstrual cycles. Current research, however, indicates that girls with CF reach menarche only slightly later than their non-CF counterparts (mean age [13.1] years, versus 12.4 years for girls that do not have CF).[10] Recent studies have supported the conclusion that poor nutrition and low percentages of body fat can delay menarche and interfere with regular menstruation. It may therefore be reasonable to assume that increasing modulator use and better therapeutic management in the CF community will translate into increased fertility.[11] For those females ineligible for modulators, including CF patients of color, their fertility may not improve.[11] Much more research is needed in this area.

Since the 1980s, researchers hypothesized that viscous mucus in the cervix, caused by inadequate fluid regulation, is the primary cause of female infertility in CF patients.[5] Fallopian tube obstruction may pose a physical barrier to conception.[6] Dr. Andrea Roe is currently exploring the disparate characteristics (e.g., amount, viscosity) of cervical mucus in women with CF who are on and not on CFTR modulators and women without CF.[7]

Poor nutritional status may also adversely impact ovulation and may lead to oligomenorrhea (infrequent menstrual periods) in CF.[6] Other factors that inhibit pregnancy in females with CF include pancreatic insufficiency, attempting pregnancy at an older age, or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).[8] Male infertility in one’s partner may also prevent pregnancy.

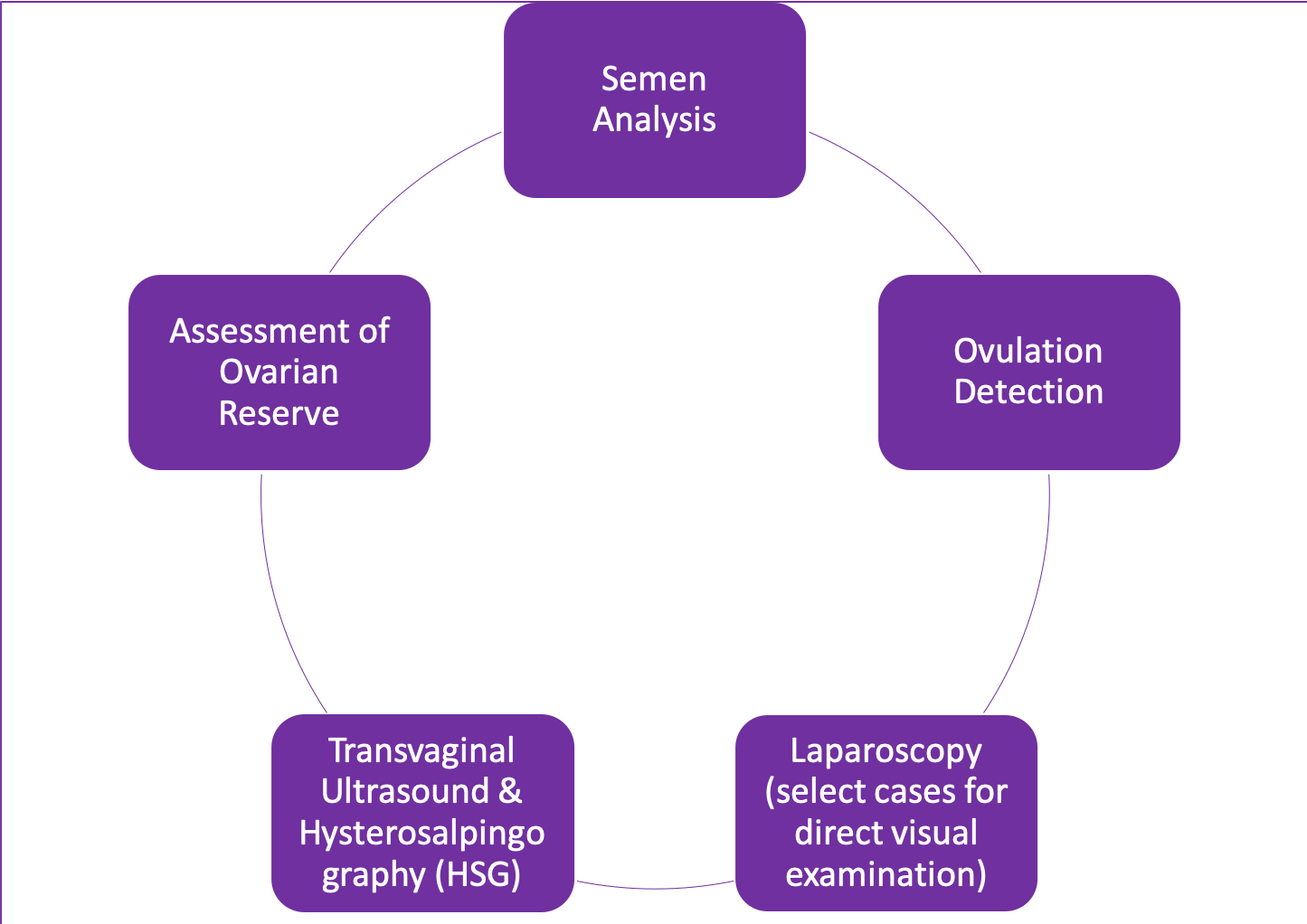

Typical Steps for Diagnosing Infertility

Infertility is customarily defined as the inability to conceive after 1 year of regular unprotected intercourse. Women typically seek an infertility evaluation by a fertility specialist after this initial year if they cannot conceive. In some cases, a physician may tell a woman to get evaluated for infertility after they cannot conceive after 6 months, but this is primarily done on a case-by-case basis. In couples where the female with CF is over the age of 35, however, most practitioners initiate a diagnostic evaluation after a couple cannot conceive after 6 months [7].

There are several recommended steps involved for a basic infertility evaluation, detailed in the graphic. A reproductive endocrinologist typically orders or performs this evaluation, although some OB/GYNs may order some testing on their own. For women in partnered relationships, it is helpful for both partners to attend the initial appointments at the fertility clinic. Both partners will likely need to undergo testing to try to determine the cause of infertility and to assess both partners’ reproductive health. Though rarely needed, a fertility provider may also order a laparoscopy so they can visually examine the patient’s pelvic anatomy and identify possible endometriosis or pelvic adhesions [7].

If testing reveals there is a fertility issue, or if the couple has been unable to conceive for a minimum of 6-12 months, then the provider will typically offer any available treatment options to enable them to pursue pregnancy. Fertility specialists may also recommend genetic testing to determine if both partners are CF carriers at the time of the initial evaluation or before any fertility treatment commences, particularly if the non-CF partner has not completed genetic testing prior to this time.

Egg Harvesting

Egg freezing (mature oocyte cryopreservation) is a method used to save women’s ability to become pregnant in the future. Eggs harvested from the ovaries are frozen unfertilized and stored for later use. A frozen egg can be thawed, combined with sperm in a lab and implanted in your uterus (in vitro fertilization) [8].

Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis/Screening (PGD/PGS)

- Preimplantation Genetic Diagnosis (PGD) is an option to consider if one or both prospective parents know they are carriers for the CF gene and want to test an embryo specifically for CF. If desired, a woman (or couple) can decide to test one or more embryos via biopsy to prevent a pregnancy with the affected embryos [9].

- Preimplantation Genetic Screening (PGS) can be done as a part of the IVF process. PGS offers the ability to test the embryo for chromosomal abnormalities when there are no known inherited disorders present in the woman/partners [10]. Like with PGD, this is performed via biopsy of the embryo.

Ovulation Induction (OI)

OI is a common treatment for women with irregular ovulation. A woman takes an oral medication, like clomid™ or letrozole™, or injectable medications, and then may have an ultrasound to determine how the ovaries respond to the medication. OI can be combined with intercourse that is timed around when a woman expects to ovulate or at the time of an intrauterine insemination (IUI) procedure, which is one type of infertility treatment.

The same medications used for OI can be used to intensify ovulation (aka superovulation), where multiple eggs are released for use in assisted reproductive technologies, like IVF. Typically, only one egg is ovulated at a time [11].

IUI (Intrauterine Insemination)

IUI is a procedure that involves placing sperm into a woman’s uterus when she is ovulating. This procedure is typically used for couples with unexplained infertility, minimal male factor infertility, and women with cervical mucus problems. IUI is often done in conjunction with ovulation-stimulating drugs. This medical procedure can be performed using the partner’s sperm or donor sperm. Before a physician performs IUI, s/he/they should evaluate the woman for any hormonal imbalance, infection, or structural problem. Separately or together, the latter set of issues may contraindicate IUI [12]

IVF (In Vitro Fertilization)

IVF is a technique where a woman’s eggs and man’s sperm are combined in a special laboratory to create an embryo(s). Depending on the diagnosis and age of the woman, an embryo or embryos are transferred to the woman’s uterus through her cervix [11]

IVF consists of 4 steps: (1) Ovulation Induction: The patient uses medications or hormones to stimulate the ovaries to produce one or more eggs; (2) Egg Retrieval: Typically under light pain medication and sedation, the doctor inserts a very thin needle through the upper vaginal wall and removes fluid–which contains eggs– from the follicles of the ovaries. Immediately after the retrieval of the follicle(s), technicians place the egg in a dish and transfer it to an incubator; (3) Fertilization: The partner or a donor provides a sperm sample, which is analyzed and added to the retrieved egg(s). A doctor may choose to inject the sperm directly into the egg to optimize success; (4) Embryo Transfer: The doctor places a speculum into the woman’s vagina and transfers the embryo(s), fresh or previously frozen and thawed, via a small plastic tube into the uterine cavity through the cervix. After the transfer, the patient receives a pregnancy test. This test usually is given after the embryos are about two weeks past the time of ovulation, or at 4 weeks of pregnancy [11].

What to do with excess embryos:

When there are excess embryos, the woman (or couple) can opt to do 1 of 5 things: 1) store their embryos for an annual fee; 2) have a compassionate transfer (embryos are thawed and transferred at a time when she is less likely to become pregnant); 3) dispose of the embryos; 4) donate the embryos to research; or 5) donate the embryos to someone who could use them in their IVF cycle [8].

Special Fertility Treatment Considerations for Women with CF

-

- Even with the presence of thick cervical mucus, the physician should still be able to transfer the embryo in an IVF procedure [13]. Some reproductive endocrinologists will choose to perform a “mock transfer” ahead of the real procedure, to enable a clear path to the woman’s uterus.

- Achieving pregnancy through IVF poses additional hazards for women with CF or patients who have a transplant. For one, the medications doctors give to stimulate the ovaries to produce eggs may result in ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, which can, in turn, cause severe respiratory compromise. To prevent this possibility, physicians can prescribe a gentle stimulation regimen, closely monitor the woman’s treatment cycle, and establish a low threshold for cancelling that cycle. Second, since multiple pregnancy is associated with increased maternal complications, it should ideally be avoided if the patient has CF. A multiple pregnancy (with twins, triplets, or more) increases the size of the uterus which can lead to respiratory compromise for the carrier. If a multiple pregnancy does arise, the woman may need to seriously consider selective reduction (termination) to carry only one baby in the pregnancy. The fertility specialist, the obstetrics care provider, the CF physician, and the patient should communicate regularly to ensure that these issues are addressed [14,15].

- Many women with CF wonder if pursuing infertility treatment might affect their pulmonary and overall health status but there is no research that explores these concerns.

- To learn what to expect while pregnant with CF, read the Pregnancy chapter in this guide.

Surrogacy

Surrogacy is an option for women with CF, and for many women, the same IVF process described above can be used to create embryos for surrogacy. A woman with CF may want to consider surrogacy if she has the ability to create embryos through IVF, but does not want to or is not physically healthy enough to carry a pregnancy [see the Family Building chapter for CF-specific considerations for surrogacy]. When considering this option, it is important that the woman understand her state’s surrogacy laws before she starts. A woman with CF might first ask her fertility doctor for recommendations on how to secure a surrogate. She may also reach out to family and close friends to find a volunteer surrogate prior to looking into surrogate agencies. If a surrogate is located nearby, attending appointments and arranging to be at the hospital for delivery might be much easier. Further, a surrogacy lawyer is required both for the intended parents and the surrogate to complete the process; hiring a lawyer avoids legal issues between the prospective parent(s) and the surrogate. The prospective parent(s) and surrogate can decide, before entering into such a contract, whether either party can post on social media, how much the prospective parents will pay for necessities and pampering, and whether medical costs will be covered through an insurance plan or out of pocket.

Prospective parents will also need to create a birth plan with the surrogate. The intended parents can do a hospital tour to become comfortable with the birth plan; they should tell the hospital staff about the surrogacy arrangement before the birth. The woman with CF might want to share with the hospital staff that she has CF so they know to keep things extra-sanitary. The prospective parent(s) may be able to detail who will be in the room during the birth and can talk to the hospital about potential plans for after the delivery. In addition, before the baby is born, the prospective parent(s) and surrogate may discuss whether or not the surrogate will attempt to pump breast milk.

My husband and I started to discuss starting a family a year or so after we got married. We saw a fertility doctor who did not give us the information we were looking for. He said everything should be fine with me carrying and we should start trying right away; that just didn’t seem like the safest and most well thought out decision. We waited a year and went back to the same fertility clinic to see a different doctor. Our doctor was amazing and set us up with a Maternal Fetal Medicine specialist. Our MFM was a huge help and said it wasn’t impossible for me to carry, but there are a lot of unknowns, especially with my surgery from childhood and total bowel obstruction in 1998. Once we decided, it was quite an easy journey. I did one round of IVF and had our egg retrieval. My body did well with the meds and I had no issues. After the process and genetic testing on the embryos, we had 3 healthy embryos. We worked with an IVF clinic and a woman and her husband had messaged the clinic saying they wanted to be a surrogate for someone in need. So, we didn’t have to use an agency. We had to check a lot of boxes before the embryo transfer (therapy sessions with our surrogate and her partner, numerous check ups to see if her body was prepared and able to carry our baby, etc). We implanted one embryo and found out it took two weeks later. We went to every doctor’s appointment and were very present with our surrogate on the journey. The hardest part of the journey was not feeling your baby kick, not having people ask…when are you due, etc; it was also out of your control. Our surrogate was amazing, and we wrote out a detailed contract with our lawyer but wish we would’ve been even more descriptive. Another situation that came up a lot during the process was a sense of guilt. I always felt guilty if I asked her to not eat something or asked her to not post a picture, etc. I always felt guilty but had to realize we were a part of this, as well, and I needed to be honest…and we were paying a lot of money, so I need to be upfront about my worries. Bottom line, she was amazing and it was a very different, but rewarding process. I urge intended parents (biological parents) to be as open and honest in the process as they can and up front with worries, fears, etc. I feel so lucky to have had the experience we had and, in the end, have an incredible daughter and my health.

Fertility and Lung Transplants

Case series studies report that 21% of women post-transplant require medication or assisted reproductive technology (ART) to conceive. This subgroup of CF women typically requires these interventions because of low nutritional status, cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD), and changes to the cervical mucus during ovulation.

Pre-transplant, women with CF often wonder about the options for fertility preservation. CF Nurse researcher Sigrid Ladores, Ph.D., currently has an NIH grant to examine this issue. Her goal is to establish clinical practice guidelines about fertility preservation for the transplant population [15].

The Impact of Modulators on Infertility

With modulator therapy, a “modulator baby boom” is underway.[1] Modulators have certainly affected female fertility.[1] A study by Corcoran, Campbell, and Ladores about providers’ perspectives on fertility and fertility preservation reported that half of their participants had witnessed an increase in pregnancies since their patients started HEMT.[1]

These observations are confirmed in the data reported in the CF Foundation’s Patient Registry. In 2019, there were 310 pregnancies, which was an an increase attributed to improved medical care; in 2021, after many women began HEMT, the registry reported 675 pregnancies and a rise in unplanned pregnancies.[2,3] Likewise, as Kazmerski et al note: “[a] 2005 Australian survey found that 84% of men with CF wanted children, whereas a 2018 survey found that 78% of adolescent and young adult women with CF in the United States intended to become parents.”[4] Given these desires, CF clinics have a need to integrate comprehensive, age-appropriate discussions about family planning, including contraception and discussions about fertility and infertility, into CF care.[4]

For men, infertility remains at approximately 98%, due to congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens (CBAVD) and other conditions; these conditions are not affected by HEMT.[3–5] However, men generally have sperm that can be retrieved, and there are several different reproductive technologies available to them that can assist.[3–5] (For more detail, see Male Health and CF chapter).

Though there is excitement about the effects of modulator therapy on fertility in women, people who do not take modulators because of their side effects, or because they do not have the mutations that current modulators can treat, may feel left behind. About 10% of people with CF are not eligible for HEMT because of their genotype and this population is disproportionately Black, Asian, or other minority ethnicities.[3,6] This disparity in access to HEMT may disproportionately affect the fertility of ethnic minorities.

Reworking Clinic Care with Increasing CF Reproductive Needs

Our Patient Task Force (PTF) session on (In)fertility (3.26.2020) revealed that providers who discuss reproductive issues with patients often react to patients’ inquiries, rather than proactively seek out such conversations [17]. Providers typically discuss reproductive issues after an initial discussion with the parents of a recently diagnosed child with CF [14]. Since CF-related concerns often consume the entire clinic visit, providers have infrequent opportunities to address important reproductive issues, like fertility. Sometimes they raise the topic when a woman’s reproductive plans and decisions are less salient in the patient’s life [14]. Our PTF discussions also revealed that women with CF may underestimate the degree to which they are fertile, and so they may not use reliable methods of birth control. Our dialogue confirmed that women with CF need more accurate information about their potential fertility from their providers [2].

Part of ensuring optimal sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care for females with CF is making sure that they receive adequate education and health care before attempting to become pregnant. However, many studies show that young women with CF, in particular, have lower rates of SRH education, and fewer rates of screening for STIs, fewer cervical cancer screenings, and fewer pelvic exams.[7] Existing research has found that older adolescent and young adult women with CF prefer to have their healthcare providers begin the discussion about family planning and fertility. Older women with CF, however, prefer to bring up the topic themselves.[4] Regardless, females want discussions about fertility and family planning to be tailored to their specific CF needs. Reproductive endocrinologists, high-risk OB/GYNS, and other specialists, however, are generally not part of the CF center care team, leading to fragmented care.[4] In addition, healthcare providers outside of the CF center are not likely to have much knowledge of the drugs used by CF patients, including HEMT.[4]

New modulator therapies are highlighting the importance of sexual and reproductive health counseling for CF patients. This counseling should start early in adolescence and becoming more detailed as the patient ages.[3] It is important that this counseling be tailored to each patient, and that it takes into account the risks and benefits of fertility treatments and pregnancy, as appropriate. These discussions should also include contraception and family planning options. (See Family Building chapter; Support Clinics Can Offer section). More research is needed about fertility and family planning with modulator use.

Despite the need for more reproductive counseling, according to Corcoran et al (2023), many CF providers do not feel that their knowledge is adequate to address patients’ needs about fertility and pregnancy.[1] A possible solution to this issue is for CF clinics to develop specific relationships with fertility, maternal health, and fetal health providers so that the special concerns of CF patients are recognized and supported.

Psychosocial Aspects and Infertility

Infertility can be a long journey. While medical interventions may offer much-needed help, they may also add to the stress, anxiety, and grief that patients are already experiencing from infertility itself. Experiencing infertility can negatively impact the partners’ relationship as they embark on the journey; so too can infertility affect relationships with family and friends. Couples who experience infertility, for instance, may avoid interacting socially with their pregnant counterparts or with those who have children simply because it may too painful to be reminded of their trouble conceiving [1]. Other stresses of infertility can include side effects from medications, medical costs, and the presence of adequate insurance coverage [1]. It’s also difficult for prospective parents to know when to stop seeking infertility treatments. Should they stop when the toll it takes on the female body is too much, when relationships are stressed, or when their finances are tapped out? If one partner wants to end treatment before another, the couple’s disparate wishes can strain the relationship. Most patients need to gradually, sometimes with great difficulty, make the transition from wanting biological children to pursuing adoption or to come to terms with being child-free [1]. For other options to start a family, see the Family Building Choices chapter in this guide.

[Mental Health and Infertility

Mental Health

Though improved therapies and management have lengthened the lives of people with CF, and made having children possible, grappling with fertility and infertility can still be a difficult journey. Mental health concerns during this stage of people’s lives therefore need special consideration. Kazmerski et al. note that “[i]nfertility or pregnancy loss may result in stress, anxiety, or depression for both men and women.”[4] For men and women struggling with infertility or other reproductive concerns, the more complicated paths to parenthood can induce feelings of grief and loss, can impact their relationships, and can raise concerns about what to disclose to their families.[4] Adoption with a serious, chronic disease, for instance, can be a tremendous source of anxiety.[8]

Sometimes the CF clinic itself can be a source of anxiety during the time in which a person with CF negotiates family planning. Because sexual and reproductive health discussions and care are not yet fully integrated into the CF clinic setting, many patients face additional healthcare appointments with specialists and face many efforts educating them.[9] Kazmerski et al. note that patients sometimes experience disapproval from their CF care team when they express a desire to start a family. This was cited as a source of stress for these patients.[4] To be sure, transgender and gender-diverse CF patients may face additional challenges in getting appropriate support in their fertility journey but deserve the same level of care.[4]

Currently, there is very little consensus on the best-practices to help CF patients and family cope with such stressors.[4,8] Equally important, there is not enough research on the psychological needs of LGBTQIA+ people with CF or people of color with CF and their family-building journeys.[4,6] In the era of HEMT, it has become evident that patients need psychosocial care and support at every stage of their lives, especially during those years when they are dealing with fertility or infertility concerns, and when they become parents.

Peer to Peer Advice

- Meet with a high-risk OB/GYN for a preconception maternal fetal medicine consult.

- You often know your body best, especially after years of living with CF – so trust and advocate for yourself!

- Not every story about CF and getting pregnant is a difficult one.

- Find peer support. A local infertility support group can be a resource of tremendous support. Online communities of women with CF who have experienced infertility can also offer guidance.

- Remember, your strong desire to get pregnant should not supersede the need to stay healthy.

- Fertility treatments and surrogacy can be expensive. Find out before you start what your insurance will cover. Decide what you can afford.

- Decide which treatments you are willing to undertake and how many rounds of IVF you will do before starting. It helps to have a firm sense of your limit.

- Don’t be afraid to meet with a few different doctors to get opinions before deciding on what you want to do.

- Seek out a therapist to sort through your feelings. Grief can be very present when you are going through infertility, and it can take a long time to work through.

- Physically and emotionally recovering from fertility treatments can take time.

Resource Links

- The Pregnancy chapter in this guide contains more information on planning for and experiencing pregnancy.

- The Family Building chapter in this guide contains information on how to decide between your options for building your family.

- CF Trust Fertility Booklet

- National Infertility Association

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation “Assisted Reproduction and CF”

- American Surrogacy

Works Cited

- Corcoran J, Campbell C, Ladores S. Provider Perspectives on Fertility and Fertility Preservation Discussions Among Women With Cystic Fibrosis. Inq J Med Care Organ Provis Financ. 2023;60:469580231159488. doi:10.1177/00469580231159488

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry Report 2021.; 2021. Accessed November 10, 2023. https://www.cff.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/Patient-Registry-Annual-Data-Report.pdf

- McGlynn J, DeCelie-Germana JK, Kier C, Langfelder-Schwind E. Reproductive Counseling and Care in Cystic Fibrosis: A Multidisciplinary Approach for a New Therapeutic Era. Life Basel Switz. 2023;13(7):1545. doi:10.3390/life13071545

- Kazmerski TM, West NE, Jain R, et al. Family‐building and parenting considerations for people with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;57(S1):S75-S88. doi:10.1002/ppul.25620

- Yoon JC, Casella JL, Litvin M, Dobs AS. Male reproductive health in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:S105-S110. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.007

- Desai M, Hine C, Whitehouse JL, Brownlee K, Charman SC, Nagakumar P. Who are the 10%? – Non eligibility of cystic fibrosis (CF) patients for highly effective modulator therapies. Respir Med. 2022;199. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2022.106878

- Roe AH, Merjaneh L, Oxman R, Hughan KS. Gynecologic health care for females with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2021;26:100277. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100277

- Hailey CE, Tan JW, Dellon EP, Park EM. Pursuing parenthood with cystic fibrosis: Reproductive health and parenting concerns in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2019;54(8):1225-1233. doi:10.1002/ppul.24344

- Leech MM, Stransky OM, Talabi MB, Borrero S, Roe AH, Kazmerski TM. Exploring the reproductive decision support needs and preferences of women with cystic fibrosis. Contracept Stoneham Contracept. 2021;103(1):32-37. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.10.004

- Hughan KS, Daley T, Rayas MS, Kelly A, Roe A. Female reproductive health in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2019;18 Suppl 2:S95-S104. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.024

- McGarry ME, McColley SA. Cystic Fibrosis Patients of Minority Race and Ethnicity Less Likely Eligible for CFTR Modulators Based on CFTR Genotype. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;56(6):1496-1503. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.25285

- Zhang M, Brindle K, Robinson M, Ingram D, Cavany T, Morice A. Chronic cough in cystic fibrosis: the effect of modulator therapy on objective 24-h cough monitoring. ERJ Open Res. 2022;8(2):31. doi:10.1183/23120541.00031-2022

- Harvard Health. The psychological impact of infertility and its treatment: From the Harvard Mental Health Letter. https://www.health.harvard.edu/newsletter_article/The-psychological-impact-of-infertility-and-its-treatment. Updated 2009.

- Hull SC, Kass NE. Adults with cystic fibrosis and (in)fertility: How has the healthcare system responded? Journal of Andrology. 2000;21(6):809-813. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11105906/.

- Hodges CA, Palmert MR, Drumm ML. Infertility in females with cystic fibrosis is multifactorial: Evidence from mouse models. Endocrinology. 2008;149(6):2790-2797. http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/en.2007-1581. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1581.

- Geake J, Tay G, Callaway L, Bell SC. Pregnancy and cystic fibrosis: Approach to contemporary management. Obstetric Medicine. 2014;7(4):147-155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1753495X14554022. doi:10.1177/1753495X14554022.

- Roe A. CF reproductive and sexual health collaborative patient task force presentation on infertility (notes; not recorded). 4.14.2020.

- Shteinberg M, Lulu AB, Downey DG, et al. Failure to conceive in women with CF is associated with pancreatic insufficiency and advancing age. Journal of cystic fibrosis. 2019;18(4):525-529. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30366850/. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2018.10.009.

- Quaas A, Dokras A. Diagnosis and treatment of unexplained infertility. Reviews in obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;1(2):69-76. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18769664.

- Mayo Clinic. Egg freezing. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/egg-freezing/about/pac-20384556. Updated 2.1.2019.

- Resolve: The National Infertility Association. Learn about genetic screening and testing information. https://resolve.org/what-are-my-options/treatment-options/genetic-screening-and-testing

- Los Angeles IVF. USC Fertility. How does PGS work? – genetic screening . https://uscfertility.org/ivf/how-does-pgs-work/.

- Resolve: the National Infertility Association. Making decisions about remaining embryos. https://resolve.org/what-are-my-options/treatment-options/making-decisions-remaining-embryos/. Website.

- Resolve: The National Infertility Association. What is IUI? https://resolve.org/what-are-my-options/treatment-options/what-is-iui. Web site.

- Epelboin S, Hubert D, Patrat C, Abirached F, Bienvenu T, Lepercq J. Management of assisted reproductive technologies in women with cystic fibrosis. Fertility and Sterility. 2001;76(6):1280-1281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02896-5. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(01)02896-5.

- Rodgers HC, Knox AJ, Toplis PJ, Thornton SJ. Successful pregnancy and birth after IVF in a woman with cystic fibrosis: Case report. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(10):2152-2153. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/15.10.2152. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.10.2152.

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Pregnancy after transplant. pregnancy and CF. https://www.cff.org/Life-With-CF/Transitions/Family-Planning-and-Parenting-With-CF/Pregnancy-and-CF/Pregnancy-After-Transplant/. Accessed 6.25.2020.

- Jones GH, Walshaw MJ. Potential impact on fertility of new systemic therapies for cystic fibrosis. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews. 2015;16:25 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2015.07.013. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2015.07.013.

- 17. CF Reproductive and Sexual Health Collaborative. CFReSHC Patient Task Force meeting on Infertility. 4.14.2020.

Free Printable PDF Download

Want a free printable PDF download of this section for your use in clinic? Just give us your name and email address below to get your download link. This will not add you to our email list.