Sex, Gender, & Sexuality

Although sex and gender are often used interchangably, these are actually different characteristics. The common ground between the two terms is that both are identities. In this chapter, “sexuality” is defined as the full scope of people’s sexual interests, attractions, preferences, activities, etc.CFReSHC CF-SRH Resource Guide by Patients for Providers and Patients

Although sex and gender are often used interchangably, these are actually different characteristics. The common ground between the two terms is that both are identities. “Sex” refers to how people relate to different attributes of their bodies, like genital anatomy and genetic differences. “Gender” refers to people’s concepts of themselves as social beings–the roles they play and the expectations they have for themselves.

Based on how people’s bodies look, others often make assumptions about both sex and gender that may or may not be accurate. Sometimes people also make assumptions about sexuality based on information about sex and/or gender. But sexuality is actually its own unique characteristic–although like sex and gender, it can be an identity. In this chapter, “sexuality” is defined as the full scope of people’s sexual interests, attractions, preferences, activities, etc.

- What is your sex/gender identity and what pronouns do you use?

- Who are the important people in your life–like partners or significant others?

- Have you experienced sexual trauma or abuse?

- Do you have any concerns regarding your sex, gender, or sexuality?

- Can you help me with addressing the sexual side effects of SSRI use? of Trikafta use?

- Do you have any information about how sexual identity and CF may influence one another? Any resources to consult?

- Does having a transplant change one’s sexual care with CF?

- Can you help me find an OB/GYN and/or Sexual Health Specialist to help me with health issues related to sex and gender?

Introduction

Encountering sexism and gender bias does harm to people with and without CF, especially those who are viewed as feminine. Instead, it is advisable to have providers focus on the care needs and priorities of people with CF who were assigned female at birth (AFAB) and those who presently identify as feminine.. Patients are women, females, and/or femmes, –which can include both trans and cis people–intersex and endosex people. Building a comprehensive culture of inclusion and partnership in healthcare is of paramount importance for effective health care delivery.

Encountering sexism and gender bias does harm to people with and without CF, especially those who are viewed as feminine. Instead, it is advisable to have providers focus on the care needs and priorities of people with CF who were assigned female at birth (AFAB) and those who presently identify as feminine.. Patients are women, females, and/or femmes, –which can include both trans and cis people–intersex and endosex people. Building a comprehensive culture of inclusion and partnership in healthcare is of paramount importance for effective health care delivery.

Too often LGBTQIA+ people are treated as completely separate communities from others, and this separation often reinforces myths and misconceptions (Burton et al. 2020) about LGBTQIA+ individuals. Members of the LGBTQIA+ adult CF community understand the need for conscious and intentional inclusion of their experiences in patient spaces (see Austin et al. 2019). When health care providers treat affirming health care practices as niche topics, it can obscure the ways in which sex, gender, and sexuality can matter for people outside the LGBTQIA+ landscape (Parameshwaran et al. 2017).

A patient’s knowledge of the unique facets of their individual journey with CF is a major asset to helping providers aid their patients to reach their sexual and reproductive health goals. There is great power in asking thoughtful questions and avoiding assumptions about one’s patients. If there is one thing CF patients of all sexes, genders, and sexualities tend to love, it is being treated as experts on their own bodies! People of marginalized sexes, genders, and sexualities feel trusted when they are able to give answers to sensitive questions because marginalized populations are often accustomed to being doubted or outright shunned. Thus, promoting open bidirectional communication is crucial to providing a safe environment for discussions with patients about issues of sex, gender and sexuality.

Beginning clinical encounters with new patients by sharing information, like pronouns or another “preferred form of address,” builds trust. This can be awkward because remembering to use proper pronouns can be a new practice, but trying and stumbling is better than ignoring a request.

Providers’ nonverbal cues are also important to ensure an environment prime for discussing sex, gender, and sexuality with people of all sexualities. Some marginalized, abused and/or traumatized patients may balk at physical touch and even eye contact. Therefore, visual cues often speak louder than words in the clinical encounter.

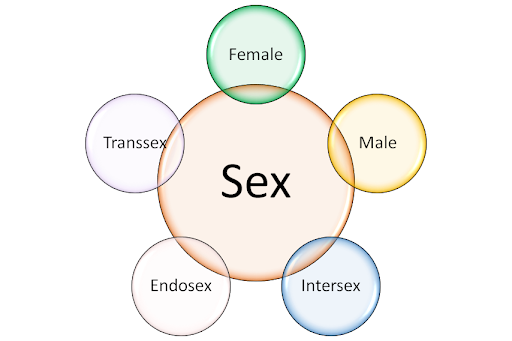

Sex

Broadly speaking, sex describes how we interpret our bodies (Fausto-Sterling 2012). This element of our identity can matter in a variety of different ways for effective sexual and reproductive health (SRH) care (Lampe & Nowakowski 2020). Little is known about how CF may influence sex characteristics and vice versa. In a CFReSHC snap poll conducted on 3/19/21,16 of 25 respondents felt distanced from the CF community because of their sex/gender/sexual orientation. Seventeen out of 30 respondents had tried to discuss sex during their clinic visit. Only six out of 28 felt their medical team was sensitive around issues of CF and sexuality. Some patients who took the poll asked to: “normalize inclusivity,” or stated: “I have tried (talking to my team about sex) and I am treated like a child…I am 40.”

Scientific Background

Sex characteristics can differ widely even in people of the same sex identity. Sometimes male and female clusters overlap, giving a person intersex characteristics (Carpenter 2018). Some intersex people identify only as intersex; some also identify as female or male (Davis 2015). Even among people without any intersex traits (those who are considered endosex), variability still exists between individuals.

There is also variability within individuals. For example, people’s anatomy at birth may not match with how their bodies look as adults. When these changes stem from intentional actions to make one’s body reflect a different sex than the one a person was assigned at birth, that is called being transsex (Sumerau & Mathers 2019). A person can also be cissex, meaning their sex was assigned correctly at birth. Many other factors can also influence changes in sexual anatomy over time, including: nonconsensual surgery performed on intersex children, consensual surgery performed on adults of all sex characteristics and identities, accidental injuries, sexual abuse, complications from other chronic conditions, and/or the process of aging itself (see Kuh & Hardy 2002).

Sexual anatomy is a distinct component of sex identity, but is not the entirety of it. An organ inventory helps identify the direction of treatment. It helps for the provider to ask about both organs a person has at present and organs they may have had in the past. Any bacteria that can colonize in the lungs can also cause issues with other organ systems, including sexual and reproductive anatomies. Patients can also have functional differences—bodies may work differently despite having the same basic anatomy. Further, organ transplants may be relevant for SRH care because they dramatically impact multiple aspects of daily life.

In the future, some people with CF may have uterine transplants in addition to transplants of other organs like the lungs, heart, liver, and kidneys. People with CF might have uterine transplants for a variety of reasons. Some people might get a uterine transplant because they were born without a uterus and want to carry a child. For example, transsex and/or intersex patients might seek this option in the future. Others might be interested in uterine transplants because their original uteri got damaged by persistent infections or other complications of CF.

There is a lack of clinical data on the aging CF population as a whole, and this dearth of information affects our knowledge of sex and sexuality in CF patients. Treatments prescribed today can impact future outcomes of aging patients and potentially cause future complications. A general lack of thorough and person-centered research with feminine people within and beyond the CF community presents additional barriers. Even studies that do address these populations specifically often misses opportunities to critically explore the experiences trans and intersex patients, as well as patients of racial and ethnic minority backgrounds. For example, we do not currently have data about how puberty blockers taken by adolescent CF patients may impact SRH health as those individuals continue to mature.

Feminine people may experience breast exams differently than those without feminine identities–and the cause of discomfort related to breast exams may be invisible. For example, pleuritic inflammation in the lungs can cause pain on contact. Transplant scarring may also be a factor in doing physical exams comfortably. Some people with CF have breast implants which can impact the process. Others may have had breast reduction surgeries and/or full mastectomies for a variety of reasons, including cancer and sex transition as well as comfort. Finally, some CF patients who have vaginas do not have enlarged breasts but should still get an exam. This can be true for trans and cis patients alike.

Not every patient with a vagina started out with one. Tissue created from vaginoplasty may not stretch or lubricate as easily as other vaginal membranes. Some people who have had vaginoplasty may also feel sensitive about having their vaginas touched because there is a fear of being perceived as inauthentic. In addition, some people who have had vaginoplasty have much vaginal depth. As a result, so-called “zero depth” or “vulvoplasty” procedures are becoming more common (Jiang et al. 2018). These types of vaginoplasty may even become favored among trans people with CF because of the comparatively lower health risks involved (see Ferrando 2020).

Conversely, intersex patients may have started out with vaginas but share some of the above concerns or have unique ones of their own. Being intersex and having CF may be especially tough because there is still such limited understanding of what intersex characteristics mean or how they intersect with other elements of CF bodies and patients’ health. Most intersex people do have some hormonal differences from their endosex peers; we are learning a lot about how hormones impact CF and vice versa (Holtrop et al. 2021). Feminine people of all sexes also often experience a lot of social pressure about whether their bodies look “right” to others. These concerns can be exacerbated by both being intersex and having CF and their intersection.

Gender

Gender describes aspects of our identities related to our social roles. It involves our bodies because the way others react to our appearance creates expectations about how we should behave (Johnson & Repta 2012). We form our own gender concepts in response to both our intrinsic feelings about ourselves and the reactions of others to us. For people with CF, the basic process of forming a gender identity and navigating it in different health care contexts may often mirror the experiences of those without this disease. However, our gender concepts may intersect in particular ways with other aspects of life with CF (Nowakowski 2019). Providers should therefore consider gender issues in SRH care planning and in the delivery of care for CF patients.

Scientific Background

Gender identity does not necessarily predict sexual and reproductive goals. Similarly, CF often impacts how we feel about our bodies and social roles. As such, the intersection between a patient’s health challenges and our gender identity may impact our SRH choices and needs in a variety of ways.

Stereotypes of disabled people, including those with CF, include assumptions about not being in agentic or leading roles in our lives and in our communities. This has often been an especially challenging experience for AFAB and otherwise feminine patients, given the overall patterns of sexism and infantilization that impact people with chronic conditions, including those with CF.

Paternalism in health care is a general problem that may have particular impacts for SRH choices and the goals of CF patients. Centering the unique wants and needs of AFAB and otherwise feminine people living with CF is an evidence-based move. As more people with CF survive to older ages, the importance of taking a goal directed approach to SRH care increases further. Quality adult CF care in SRH and other areas alike requires providers to consciously nurture patient agency and autonomy.

As highly effective CFTR modulators and other innovations in treatment facilitate changes in CF-sexual and reproductive functioning, many patients have begun to think differently about the range of choices realistically available for our futures. These drugs often thin cervical mucus substantially and induce other changes that can make it easier to conceive children (Heltshe et al. 2017). For patients who want to conceive, the impact of modulators upon cervical mucus is a welcome change. Some people who never thought about becoming parents via sexual reproduction before starting on modulators have realized that having biological children can be an attainable option for them. Conversely, many patients have cemented an understanding that they do not wish to have children by any means as they have advanced to older ages. But for people with CF who have experienced pressure to bear children or unwanted pregnancies or abortion stigma, this pathway is more fraught. In these situations, patients have gained the ability to make informed choices about their reproductive futures rather than defaulting to a sense of fatalism about what their adult lives could include. These choices can both influence and be shaped by how people’s concepts of their own gender develop and change over time.

To understand the SRH needs of gender diverse, CF patients, clinicians need opportunities to meet these types of patients.

CF impacts our bodies and can reinforce gender stereotypes and cause gender dysphoria or the difficulties related to a strong desire to be another gender. Being able to access health care services that help reduce gender dysphoria regarding how CF affects embodiment is critical. We often think of gender dysphoria as something that only trans people experience. Certainly this is a common—although by no means universal—experience among people with and without CF in the trans community. However, this narrow view of dysphoria misses many important opportunities to provide quality SRH care for people with CF of all sexes and genders.

Some experiences of dysphoria in SRH care for people with CF may be due to the disease’s progression and complications. For example, females who are unable to conceive may struggle with feelings of inadequacy as women and/or females. Likewise, some females both with and without CF may experience dysphoria from excessive questioning about reproductive goals, especially if those goals have been clearly indicated. Some females with CF regardless of their gender identity do not wish to bear children. Within the CF community specifically, dysphoria seems to have become more of a concern in the age of CFTR protein modulators.

The paramount concern in gendered care is to enable the patient to make an informed decision without any pressure from providers.There is no one authentic way to be feminine, only what feels right for a given person. At the same time, it is helpful for providers to remind patients that it is okay for their gendered, embodied experiences to shape and be shaped by CF. How CF affects patients’ lives may also change as new treatments become available and as research that informs CF care becomes more transparent and inclusive (Holman et al. 2020). As such, a provider should explicitly ask how a patient wants to be perceived and how the provider can help them achieve their goals, whether it be gender expression or reproductive wishes. This is the most direct way to provide SRH affirming care for sex and gender diverse people with CF. It is vital to have these care spaces for AFAB and otherwise feminine people with CF who experience forms of marginalization.

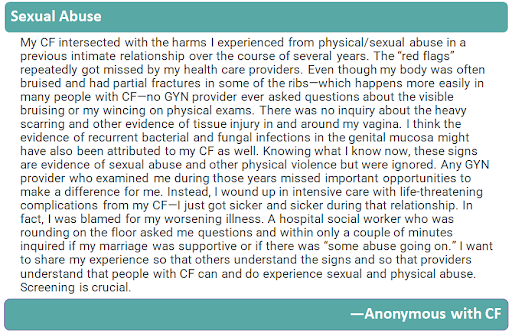

AFAB People and Abuse

Sex and gender identity, along with related forms of socialization, can impact how people with CF deal with trauma. Some AFAB patients with CF who have experienced abuse may not want to disclose their experiences. Trans, nonbinary, and/or intersex people within and beyond the CF community may be even more inhibited about disclosing abuse. It is helpful for healthcare providers to explicitly remind patients that talking about experiencing harm does not suggest weakness; it takes strength to seek support. Being vulnerable with the people who care for us requires practice and it may never feel easy. The struggle to show vulnerability is especially true in SRH spaces, which often make patients reckon with aspects of their gender identity and related struggles in their journeys with CF.

Further, people who experience abuse may not realize it. Sometimes, people who experience abuse may not recognize it or even realize it and this lack of awareness may increase the provider’s obligation to act promptly and appropriately when any signs of potential abuse surface. Living with CF may dim awareness of present abuse by enabling a sense of fatalism and acceptance of hardship, even for people who do not actually dissociate. This can inhibit patients from sharing actionable information about abuse in SRH settings, and thus can prevent patients from accessing helpful services and support.

Still, patterns of abuse in a patient’s life matter clinically for people with CF. Signs of abuse may appear differently for people with CF in both CF and SRH care contexts. Physical issues like easy bruising and tissue tearing can make abuse easier to spot in some cases. SRH providers may be able to spot signs of sexual or other physical forms of abuse early on, for instance, because of the nature of clinical exams, especially in OB/GYN care settings. In others, however, the physical nuances of CF can mask bodily harm that results from violence. For instance, a provider can explain a patient’s experiences of persistent pain from broken ribs as a result of heavy coughing, rather than from abuse.

People with CF may also struggle with recognizing and/or reporting abuse because they may face unique mental and social health issues related to coping with the disease. CF patients’ familiarity with trauma resulting from medical experiences and/or from constant messaging about adherence may impact the way patients may perceive other experiences (Carlson & Dalenberg 2020; Butcher & Nasr 2015). In addition, the pressure to follow cultural norms may diminish some patients’ sense of agency in recognizing and reporting harm inflicted upon us. This is not a widespread phenomenon documented in the clinical literature, but it is definitely an issue about which providers should be aware.

Sexuality

A complex and deeply individual phenomenon, sexuality describes the ways in which we relate to ourselves and others sexually—or not (Carroll 2018). It includes attractions, preferences, behaviors, feelings, kinks, interests, phobias, experiences, boundaries, and more. Social expectations relating to sex and gender can also influence sexuality; people can feel and behave sexually in ways that intersect with these expectations (Ritter & Nowakowski 2020). Being a chronic care patient for people with CF can often impact others’ expectations relating to their sexual interests and behaviors—or lack thereof. Some CF patients are very sexually interested and active, and others are not. Sexuality in the CF community is quite diverse and can significantly impact a patient’s SRH care needs. The next sections explore some of these potential impacts.

Scientific Background

The scientific literature on SRH affirming care in CF is scarce. Some research on stigma and CF has revealed that broad cultural attitudes about chronic disease and sexuality impacts care for people with CF in SRH settings (see Fonte et al. 2018 below). Issues of stigma, sexuality, and CF are situated within larger patterns for people with chronic illness which are described fully in the scientific literature on experiences of chronic illness.

Desexualization of people with chronic illnesses, for instance, is widely documented in the literature on chronic illness and disability. (Nowakowski 2016). Because people with CF and other disabilities are often infantilized by society, they are also often desexualized, including in health care settings (Fonte et al. 2018). Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency for patients with CF may exacerbate infantilization since it makes CF patients’ bodies very thin, and thus seem childlike; this potential link warrants further study. Finally, people with CF often experience ableism–discrimination against disabled people–relating to their sexual behavior from clinicians and non-clinicians alike (Werner et al. 2019).

People with CF certainly face unique safety and health considerations and challenges with sex (Nowakowski et al. 2020). These issues may intersect with our sexuality but do not generally prevent patients from having sex entirely. Below are some common safety and health challenges AFAB and otherwise feminine people with CF may experience during various types of sexual activity:

- Respiratory issues can limit a patient’s ability to engage in vigorous physical activity with a partner(s). Shortness of breath or feelings of suffocation are examples of possible issues people with CF can experience during sex (Goss et al. 2009). Experimenting with different sex positions can help because some allow the diaphragm to move freely and the lungs to expand more easily. Choosing a suitable position can also help patients and their partners avoid getting tangled in oxygen tubing during intercourse, if applicable. Patients may also cough up mucus plugs and/or blood clots during sex. How partners deal with these experiences varies, as does a patient’s comfort in talking about and planning for such moments.

- Hemoptysis and bleeding issues can pose similar challenges. Coughing up blood clots and fresh blood is a common occurrence among sexually mature people with CF (Flume 2009). Vaginal and anal bleeding can also occur. For instance, a sudden rush of fresh blood that appears after vaginal intercourse due to a burst blood vessel in the vaginal wall may be related to infection, as noted below, or may occur spontaneously due to the weakening of sizable blood vessels over time as CF disease progresses.

- Infection control: A patient’s anatomy can influence the types of infections people with CF and our partners may be prone to (Schwarz et al. 2018) and/or the types of discomfort or potential harm patients experience from sexual activity with their partners or with themselves. For people with CF who have transplanted lungs or other organs, preventing infections in the genital and urinary tissue may be even more challenging because immunosuppression required after transplant can predispose mucosal tissue to new bacterial or fungal colonization (Fishman 2017). Vaginal and anal intercourse are highly likely to spread different types of pathogens relative to other forms of sexual activity (Danby et al. 2016). In cases where people with CF have rigid tissue from scarring and/or fragile blood vessels, the risk of bloodborne infections becomes higher. It is also fairly easy for surface pathogens to colonize the mucus in patients’ vaginal and anal cavities and the surrounding membranes. Thorough hygiene prior to any sexual activity can help people with CF of different sexualities prevent infection proactively. Using condoms for any activities that involve penetration can also help substantially–and may be particularly important for some same sex couples because of broad differences in common sexual activities. Some types of condoms may be safer for some patients than others (Motsoane et al. 2001). For instance, latex allergy presents a central concern; nitrile condoms are an alternative, in addition to reducing latex use. Further, penetration by objects can also predispose people to infection (Wood et al. 2017). If patients are using sex toys, either alone or with partners, practicing good hygiene and using barrier methods in addition to thoroughly cleaning toys, can help to protect people with CF from dangerous infections. For their part, condoms can help reduce friction with partners’ bodies and/or toys. This can vastly improve comfort and pleasure during intercourse in addition to preventing tissue damage.

- Therapies to manage existing infections may also contribute to challenges with sex. For example, quinolone antibiotics can cause damage to the joints and connective tissue (Sendzik et al. 2009) which can exacerbate existing arthritis issues from CF and make sudden movements while having sex dangerous. Both quinolones and azithromycin can prolong the QT interval in the heartbeat, causing people to become dizzy or even lose consciousness outright (Arunachalam et al. 2018). Sexuality may thus take different forms during active infections, even when the genital mucosa themselves are not directly affected.

- Equipment used to manage CF can also pose challenges to having safe sex. External medical equipment, like colostomy bags for those who have had bowel surgery, can pose issues during sex. Implantable medical equipment, like infusion ports for people who frequently receive intravenous antibiotic therapy, can also cause problems.

People with CF who have uteri may also use intrauterine devices (IUDs) for contraception. Whether a CF patient has a copper T or hormonal coil, the presence of an IUD may heighten concerns about injury, bleeding, and/or infection in the uterine and cervical tissue (Edelman et al. 2013). It may also impact safety relating to medical devices during sex.

- Tissue rigidity and potential for tearing can introduce safety concerns for people with CF of different sexualities. Scar tissue can make certain types of activity either difficult or outright risky (Schimpf et al. 2010). Tissue rigidity in the sexual and reproductive organs of people with CF, including potential trauma history associated with these differences, can also pose challenges. A person with CF who uses particular types of sex toys or enjoys vigorous vaginal sex may experience more tearing and scarring of the genital and internal tissue than fellow CF patients who engage in different types of sexual activities, or no sex at all. Scarring may result from many different processes; some are more directly related to CF disease progression than others. The stickiness of the membranes adds a risk for tearing of the vaginal wall by increasing friction (Wiehe & Arndt 2010). Membrane stickiness may become especially problematic for people who enjoy vigorous penetration as a route to sexual pleasure. Good nutrition and adequate hydration can help by limiting the stickiness of genital mucus. However, these practices alone are unlikely to make the mucus of a person with CF as thin or slippery as their non-CF peers.

- Insufficient lubrication can exacerbate all of the above issues. The degree to which different people with CF struggle with lubrication varies, as does the precise impact of lubrication problems (Tuchman et al. 2010). Genital anatomy of both patients and their partners, individual CFTR mutations, particular sexual activities, and various other factors can all impact how lubrication issues impact people’ssexual health. Likewise, challenges with lubrication can hinder conception among people with CF who wish to become pregnant. Using lubricants during sexual activity can help mitigate some of these issues.

Discussions between a provider and a patient related to sexuality requires both to be comfortable raising the issue in clinical settings. Research is just starting to touch on the nuances of different sexualities and how they intersect with CF health care (Schrock et al. 2014). The existing literature makes clear that patients cannot be expected to talk openly about their own experiences without having providers sending clear signals that the patient is safe to do so. The more healthcare providers welcome talking with their patients about the experiences of people of different sexualities with CF, the easier it becomes to talk through these issues.

Further, discussions around patients’ sexual practices, and how CF impacts them openly, can help maximize quality care. Whatever their specific sexualities may be, all patients can benefit from the ability to talk about these aspects of their lives and how their health intersects with sexuality while receiving SRH care. Understanding that each person with CF is unique in their sexual identities, desires, and experiences can help SRH providers create affirming spaces for these discussions.

When SRH or CF providers have discussions with patients about these issues, they can try to avoid making assumptions about what kinds of sexual activities a particular person with CF may be doing, or what needs they may have related to these activities. To know what kinds of sexual activities and experiences are relevant for the care of a particular person with CF, a provider must ask them.

Overall, open discussions about sexual practices and CF communicate caring and affirmation for people of all different sexualities. These types of conversations help patients feel more at ease sharing their lived experiences. Having preliminary conversations about these issues can communicate to the patient that their choices matter. This message can help patients explore their preferences on their own and can facilitate effective dialogue with their partners.

Some of the same practices recommended for helping people with CF of different sexes and genders feel safe and welcome in their communities can also apply to clinic discussions. Providers and patients can share their pronouns; a clinic can have images posted of people in different types of intimate relationships; a clinic can provide a thorough list of options relating to how people can describe their different identities on paperwork; and a clinic can hire staff whose lived experiences reflect the diversity of our community.

Types of Sexualities

There are no real fixed patterns of number or intensity of sexual relationships by types of attractions, except for some asexual and demisexual patients. “Asexual” describes people who have limited interest in sex; “demisexual” describes people who are only interested in sex when they feel emotional closeness with people (Chasin 2011). These are distinct sexual identities like being gay or lesbian (experiencing attraction mostly to people of one’s own sex) or being bisexual or pansexual (experiencing attraction to people of one’s own sex as well as other sexes) (Pinto 2014). People who are asexual and demisexual often consider themselves to be part of the broader queer community, as do people of other non-hetero sexualities.

People who are asexual or demisexual often have more limited sexual histories and fewer lifetime partners, although this is not always the case. Some people who are very sexual may have low numbers of past partners and/or gaps in their sexual histories. These patterns may or may not have any direct relation to CF disease, though they can affect forms of CF embodiment. For example, someone might be less sexually active during a prolonged period of hospitalization or intensive illness management at home. Another person with CF might be celibate for a couple of years for personal reasons not directly related to the disease, such as a history of abuse or recovery from addiction. These scenarios apply to both people who tend to be “monogamous” or “mono” and to those who tend to have more than one partner at a time, that is, “polyamorous” or “poly” (Simula et al. 2019).

SRH providers can remind patients with CF that different forms of sexual activity may be more suitable at different times. Pleasure can come from a wide array of different activities, whether with partners or by oneself. It does not have to include contact with the gentical mucosa. Sexual activities that do not involve any genital contact may be especially attractive for people with CF during times when the pelvic mucosa are actively infected or sore or when the patient does not feel as well or energetic.

Patients with multiple partners may need extra support and reminders about certain safe sex practices. For example, using barrier methods is always recommended with any partners where a “fluid bond” does not previously exist (Sumerau & Nowakowski 2019). Fluid bonding for people with CF often involves additional considerations and decisions, like agreeing with one’s partner(s) that their other partners will not be intimate with anyone else who has CF. The issues surrounding partners’ behaviors makes STI testing all the more important. Early detection of STIs may be even more vital for people with CF because it is difficult to eradicate infection in mucosal tissue. Further, asexual people who do not have sex can still get STIs by other means. Providers who recommend appropriate infection control and lubrication strategies can support good SRH for CF patients of all sexualities.

Key Takeaways

- Advocating for patients can include asking for their input, acting on what is learned, and reflecting on how to improve (Nowakowski & Phillips 2021).

- Patients can help their providers realize what is missing in their clinical judgment or treatment plan.

- Literature exists on how different people with CF vary in their identities, biographies, behaviors, and goals for sexual and reproductive care, and how their clinical needs can vary as a result.

- Centering a patient’s individuality is key to achieving health care justice and reflects the core principles of person-centered care (Brummel-Smith et al. 2016). Incorporating these skills is a great way to change the culture of OB/GYN and MFM care and to make team-based CF clinic care more inclusive for CF patients. Person-centered care requires creative discovery and collaboration (Taylor et al. 2018). Patients can be seen as partners.

- Being active stewards of your own health is common among AFAB and feminine people because of their socialization. For people with CF across all sex and gender groups, proactively managing their health is also an essential.

- Providers and patients can ask questions to one another about CF-SRH. An open dialogue that reflects curiosity and caring can benefit both providers and patients. When patients feel comfortable with their provider, they are more inclined to inform their providers when something feels wrong, or when they need something different. Asking questions, trusting the answers and implementing any changes promotes patient centered care and bi-directional communication.

Peer to Peer Advice

- Try to address any infantilizing behaviors or statements in your clinical care and elsewhere. We are adult, sexual beings.

- Advocate for seeing complex pharmacists to see how different medications may affect your sexual issues (ie: low libido).

- Seek support when going through changes physically–whether related to organ transplants or sex reassignment.

What We Want to Know More About

- How can we make inclusivity and intersectionality permanent principles in clinics across the US?

- What is the transgender transition like for different patients with CF?

- What are the comparative, differential health outcomes between cisgender and transgender patients with CF when considering hormonal medications? How do CF medications and hormones affect patients differently when taken in combination with one another?

- How does organ transplant impact the SRH care needs and goals of people with CF?

Works Cited

- Burton CW, Nolasco K, Holmes D. Queering nursing curricula: Understanding and increasing attention to LGBTQIA+ health needs. Journal of professional nursing. 2021;37(1):101-107. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2020.07.003.

- Austin JM, Foscolos A, Bennet N, Allison jJ, Trobaugh J. Addressing bias in LGBTQIA+ undergraduate medical education: An innovative and community based approach to curriculum reform. . 2019. doi: 10.13028/gnpx-n983.

- Parameshwaran V, Cockbain BC, Hillyard M, Price JR. Is the lack of specific lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) health care education in medical school a cause for concern? evidence from a survey of knowledge and practice among UK medical students. Journal of homosexuality. 2017;64(3):367-381. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2016.1190218.

- Fausto-Sterling A. Sex/gender. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge; 2012. doi: 10.4324/9780203127971.

- Lampe NM, Nowakowski A. New horizons in trans and non-binary health care: Bridging identity affirmation with chronicity management in sexual and reproductive services. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2020:1-3.

- Carpenter M. Intersex variations, human rights, and the international classification of diseases. Health and human rights. 2018;20(2):205-214. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26542072.

- Davis G. Contesting intersex. New York: NYU Press; 2015. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt15zc7ht.

- Sumerau JE, Mathers LAB. America through transgender eyes. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield; 2019.

- Kuh D, Hardy R. A life course approach to women’s health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780192632890.001.0001.

- Jiang D, Witten J, Berli J, Dugi D. Does depth matter? factors affecting choice of vulvoplasty over vaginoplasty as gender-affirming genital surgery for transgender women. Journal of sexual medicine. 2018;15(6):902-906. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.03.085.

- Ferrando CA. Adverse events associated with gender affirming vaginoplasty surgery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2020;223(2):267.e1-267.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.033.

- Holtrop M, Heltshe S, Shabanova V, et al. A prospective study of the effects of sex hormones on lung function and inflammation in women with cystic fibrosis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2021. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202008-1064OC.

- Johnson JL, Repta R .Sex and gender: Beyond the binaries. in Oliffe J. L. and Greaves L., eds. Designing and conducting gender, sex, and health research. Sage Publications; 2012, 17-37.

- Nowakowski A. The salt without the girl: Negotiating embodied identity as an agender person with cystic fibrosis. Social sciences (Basel). 2019;8(3):78. doi: 10.3390/socsci8030078.

- Heltshe SL, Godfrey EM, Josephy T, Aitken ML, Taylor-Cousar JL. Pregnancy among cystic fibrosis women in the era of CFTR modulators. Journal of cystic fibrosis. 2017;16(6):687-694. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.01.008.

- Holman B, DeVito NJ, Vassar M. Transparency and diversity in cystic fibrosis research. The Lancet (British edition). 2020;396(10251):601-602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30905-3.

- Carlson EB, Dalenberg CJ. A conceptual framework for the impact of traumatic experiences. Trauma, violence & abuse. 2000;1(1):4-28. doi: 10.1177/1524838000001001002.

- Butcher JL, Nasr SZ. Direct observation of respiratory treatments in cystic fibrosis: Parent–child interactions relate to medical regimen adherence. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2015;40(1):8-17. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu074.

- Carroll JL. Sexuality now. Cengage Learning; 2018. https://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=none&isbn=9781337672061&uid=none.

- Ritter LJ, Nowakowski ACH. Sexual deviance in health and aging. Blue Ridge Summit: Lexington Books; 2020. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Sexual_Deviance_in_Health_and_Aging/RQ8LEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=sexual+deviance+and+aging&printsec=frontcover

- Fonte D, Lagouanelle-Simeoni M, Apostolidis T. “Behave like a responsible adult” – relation between social identity and psychosocial skills at stake in self-management of a chronic disease. Self and identity. 2018;17(2):194-210. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2017.1371636.

- Nowakowski A. You poor thing: A retrospective autoethnography of visible chronic illness as a symbolic vanishing act. Qualitative report. 2016;21(9):1615. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2296.

- Werner S, Halpern A, Kurz S, Rosenne H. Disclosure in cystic fibrosis: A qualitative study. Journal of social issues. 2019;75(3):881-903. doi: 10.1111/josi.12338.

- Goss CH, Edwards TC, Ramsey BW, Aitken ML, Patrick DL. Patient-reported respiratory symptoms in cystic fibrosis. Journal of cystic fibrosis. 2009;8(4):245-252. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2009.04.003.

- Garcia B, Flume PA. Pulmonary complications of cystic fibrosis. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2019;40(6):804-809. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1697639.

- Schwarz C, Hartl D, Eickmeier O, et al. Progress in definition, prevention and treatment of fungal infections in cystic fibrosis. Mycopathologia. 2018;183(1):21-32. doi: 10.1007/s11046-017-0182-0.

- Fishman JA. Infection in organ transplantation. American journal of transplantation. 2017;17(4):856-879. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14208.

- Danby C, Cosentino L, Rabe L, et al. Patterns of extragenital chlamydia and gonorrhea in women and men who have sex with men reporting a history of receptive anal intercourse. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2016;43(2):105-109. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000384.

- Motsoane NA, Pretorius E, Bester MJ, Becker PJ. The biological safety of condom material can be determined using an in vitro cell culture system. Analytical cellular pathology. 2001;23(2):51-59. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11904460. doi: 10.1155/2001/172657.

- Wood J, Crann S, Cunningham S, Money D, O’Doherty K. A cross-sectional survey of sex toy use, characteristics of sex toy use hygiene behaviours, and vulvovaginal health outcomes in canada. The Canadian journal of human sexuality. 2017;26(3):196-204. doi: 10.3138/cjhs.2017-0016.

- Sendzik J, Lode H, Stahlmann R. Quinolone-induced arthropathy: An update focusing on new mechanistic and clinical data. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 2008;33(3):194-200. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.08.004.

- Arunachalam K, Lakshmanan S, Maan A, Kumar N, Dominic P. Impact of drug induced long QT syndrome: A systematic review. Journal of clinical medicine research. 2018;10(5):384-390. doi: 10.14740/jocmr3338w.

- Berger GS, Edelman DA, Keith L. Intrauterine devices and their complications. Springer; 2013. https://www.vlebooks.com/vleweb/product/openreader?id=none&isbn=9789401507240.

- Schimpf M, Harvie H, Omotosho T, et al. Does vaginal size impact sexual activity and function? Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(4):447-452. doi: 10.1007/s00192-009-1051-2.

- Wiehe M, Arndt K. Cystic fibrosis: A systems review. AANA journal. 2010;78(3):246-251. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20572412.

- Tuchman LK, Kalogiros ID, Forke CM, Schwarz DF, Kinsman SB. Reproductive knowledge and preferences of adolescents and adults with cystic fibrosis: A web-based assessment. International journal of sexual health. 2010;22(2):72-83. doi: 10.1080/19317610903458960.

- Schrock D, Sumerau JE, Ueno K, eds. Sexualities. McLeod Jane D. and Abelson Miriam J., eds. Handbook of the Social Psychology of Inequality. Dordrecht [u.a.]: Springer; 2014.

- DeLuzio CC. Theoretical issues in the study of asexuality. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(4):713-723. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9757-x.

- Pinto SA. ASEXUally: On being an ally to the asexual community. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling. 2014;8(4):331-343. doi: 10.1080/15538605.2014.960130.

- Simula BL, Sumerau JE, Miller A. Expanding the rainbow. Vol 2. Leiden ; Boston: Brill Sense; 2019.

- Sumerau JE, Nowakowski X, Nowalkowski A, eds. Relational fluidity: Somewhere between polyamory and monogamy. Expanding the rainbow. Boston: Brill Sense; 2019.

- Nowakowski A, Phillips S, eds. Do ask, do act! . in Sumerau J. E., ed. Handbook of transgender studies. Rowman & Littlefield; 2021.

- Brummel‐Smith K, Butler D, Frieder M, et al. Person-centered care: A definition and essential elements. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS). 2016;64(1):15-18. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13866.

- Taylor C, Lynn P, Bartlett JL. Fundamentals of nursing : The art and science of person-centered care. Ninth edition, international edition ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2019.

Free Printable PDF Download

Want a free printable PDF download of this section for your use in clinic? Just give us your name and email address below to get your download link. This will not add you to our email list.