CF and Male Health

Males with CF face specific sexual and reproductive health challenges different from their non-CF counterparts and females with CF.CFReSHC CF-SRH Resource Guide by Patients for Providers and Patients

In this section:

- Introduction

- Key

- Priority Questions

- Glossary

- Pubertal Delay

- Sexual Function

- Gaps in Patient-Provider Communication

- Testosterone and Hypogonadism

- Spermatogenesis and Azoospermi

- Male Infertility

- Assistance Reproductive Technology (ART)

- Parenthood

- Genetic Counseling

- Sexual Function and Psychosocial Issues

- Conclusion

- Resources

- Works Cited

Sections for Providers in Blue

Sections for Patients in Green

Sections for Providers AND Patients in White

- Do you understand the physiological issues associated with reproductive organs for men with CF?

- Do you notice any troubles with your physical sexual performance, libido, sexual interest, energy or body mass that are concerning to you?

- Do you use condoms or other contraception when having penetrative sex?

- Are you concerned about the prevalence of low testosterone in males with CF? Would you like to be evaluated for this?

- Other ways that hormone imbalances can affect your health such as cholesterol

- Are you interested in having biological children?

- Are you concerned about any aspect of your sexual health?

- Do you have any sexual symptoms that you want to talk about?

- If I were to want to have children, what do the options look like?

- How would I proceed for being evaluated for fertility and or hormone levels?

- How are male CF patients treated for hormone replacement therapy if needed?

- How does low testosterone affect muscle development, bone density, and sleep cycles in males with CF?

- What role can male sex hormones play in my mental health?

- Does the fact that I have no vas deferens have any lifetime impact on my prostate? Could it cause other urologic health risks?

- How common is it for males with CF to have painful orgasms? What are the reasons for this?

- Can low testosterone or other hormone imbalances affect body/joint/muscle pain?

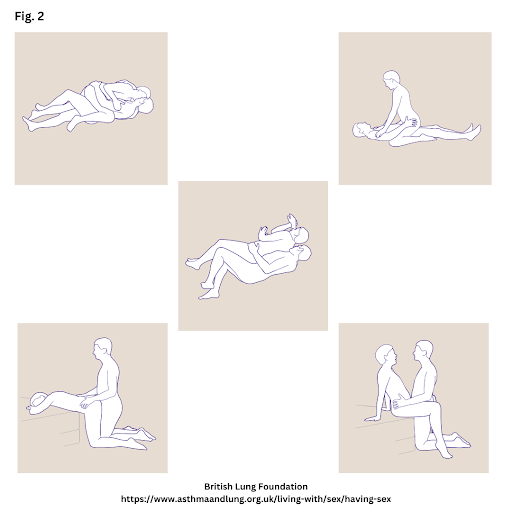

Azoospermia: the absence of spermatozoa in the ejaculate. It is a leading cause of male infertility.1 In CF, the absence of the vas deferens means that male ejaculate does not contain sperm.

Azoospermia: the absence of spermatozoa in the ejaculate. It is a leading cause of male infertility.1 In CF, the absence of the vas deferens means that male ejaculate does not contain sperm.

Hypogonadism: a condition in which there is a lack of testosterone, the hormone that is key to male development and function.2

Infertility: incapable of or unsuccessful in achieving pregnancy after 12 months of unprotected sex.3

Sex Hormones: also known as sex steroids, gonadal steroids, and gonadocorticoids. The gonads and adrenal glands produce them. They regulate sex-related characteristics and skeletal growth, cholesterol, the distribution of body fat, and inflammatory responses in the body. 4,5

Spermatogenesis: the process of sperm cell production.6 Sperm or spermatozoa contain a male’s genetic material.

Sterility: the inability to produce a biological child.7

Testosterone: the main sex hormone driving male sexual development. Testosterone plays a part in many organ systems, including the brain, nervous system, muscles, and bones. It is key to male puberty and sexual function.8

Males with Cystic Fibrosis (CF) are concerned about their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) because it can impact their mental health and their relationships with their partners, especially as their life expectancy has increased with new therapeutic advances.9 Cystic Fibrosis sexual and reproductive health (CF-SRH) discussions for the male population have generally focused on infertility and have ignored other issues that males might face, such as hormonal imbalances, body image challenges, and sexual function issues. This chapter reviews the state of knowledge on male SRH issues in the CF population–where many gaps exist, and extant research is dated–and offers resources for providers and patients on this subject.

Males with Cystic Fibrosis (CF) are concerned about their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) because it can impact their mental health and their relationships with their partners, especially as their life expectancy has increased with new therapeutic advances.9 Cystic Fibrosis sexual and reproductive health (CF-SRH) discussions for the male population have generally focused on infertility and have ignored other issues that males might face, such as hormonal imbalances, body image challenges, and sexual function issues. This chapter reviews the state of knowledge on male SRH issues in the CF population–where many gaps exist, and extant research is dated–and offers resources for providers and patients on this subject.

Pubertal Delay

Male puberty denotes the physical changes that occur as the male gonads develop, typically between ages 9 and 14.10 Researchers have long studied pubertal developmental delays in individuals with CF, identifying disease and treatment-specific factors that contribute to such delay, namely, nutritional deficiency, increased caloric requirements, and abnormal growth and sex hormone production as well as the frequent use of corticosteroids.11 As opposed to this earlier research, work since the mid-2000s has found normal or near normal pubertal development in CF youth.12 Still, researchers like Goldsweig et al. advocate for pubertal assessment because the delay of puberty can influence height, bone density, body image, and psychosocial well-being.12 Moreover, an assessment can identify causes for delay that may not be attributable to CF.10 If a physician identifies pubertal delay, the patient can initiate hormonal supplementation to induce pubertal changes.10

Sexual Function

Individuals with CF have the same desire for physical intimacy as their non-CF peers. According to West et al., males with CF typically undertake similar types of sexual behaviors and activities as their non-CF peers, “including number of sexual partners, age of sexual debut, and performance and receipt of oral, vaginal, and anal sex.”10 Yet males with CF also face different issues than their non-CF peers. For example, males with CF might experience body image issues due to having a shorter stature, lower muscle mass, and lower body weight.10 No recent studies, however, have measured the impact of these males’ physical perceptions on their mental health or quality of life. Yet such concerns could negatively influence an individual’s self-perception of masculinity and their relationships.11

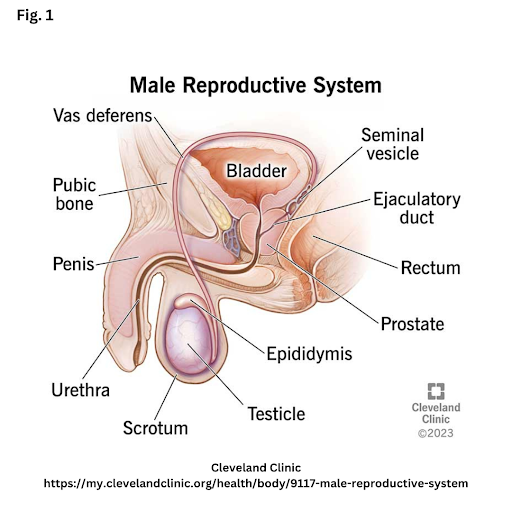

Males with CF often face several challenges with sexual function, which can include issues with intercourse, ejaculation, erectile dysfunction, or incontinence. Such dysfunctions can influence an individual’s intimate relationships, mental health, and quality of life.13 Depending upon their disease status and progression, males with CF may experience a variety of challenges during intercourse because of low stamina, low lung function, low libido, or physical discomfort. Thus, to improve sexual intercourse, patients are counseled to complete a breathing treatment before sex, to reduce breathing irritants (such as products with strong odors), and to use sexual positions that reduce shortness of breath (see Figure 2).11

Males with CF often face several challenges with sexual function, which can include issues with intercourse, ejaculation, erectile dysfunction, or incontinence. Such dysfunctions can influence an individual’s intimate relationships, mental health, and quality of life.13 Depending upon their disease status and progression, males with CF may experience a variety of challenges during intercourse because of low stamina, low lung function, low libido, or physical discomfort. Thus, to improve sexual intercourse, patients are counseled to complete a breathing treatment before sex, to reduce breathing irritants (such as products with strong odors), and to use sexual positions that reduce shortness of breath (see Figure 2).11

Ejaculation issues may form a second sexual function challenge for males with CF. Clarke et al. found that 65% of males reported sexual dysfunction, primarily because of issues related to ejaculation.14 While males with CF can and do experience erections and ejaculation, the amount of their ejaculate may be smaller than their non-CF counterparts because it does not contain sperm or normal levels of ejaculate fluids. This results from a physiological difference in males with CF, where the vast majority do not have a (or have a blocked) vas deferens. Though 90% of males with CF have normal sperm production, fewer than 5% are fertile because of this difference.13,15,16 Still, adolescent males with CF should undergo a semen analysis because a small percentage are fertile.17 Instead, semen analysis usually occurs much later, during marriage or family planning.18

CF may also affect how the prostate develops and functions, which can lead to some difficulty or discomfort with ejaculation. Although the prevalence of erectile dysfunction in males with CF is unknown, this phenomenon can also be part of sexual function issues.13

Incontinence is another issue affecting sexual function among males with CF. Incontinence involves gas, stool, or urine leakage during exertion activities, like sexual activity, coughing, sneezing, or laughing.11,15,19 Unfortunately, according to Frayman et al., this topic is understudied, but we know that in adult men, the prevalence of urinary incontinence “ranges from 5% to 15%.”20 For its part, another 2018 study of 60 CF patients found that 25% of males experienced gas, and 6% experienced fecal incontinence.19 Any leakage can be embarrassing and negatively impact an individual’s “recreational, social, and intimate activities.”20 It can also lead to depression and anxiety.20 Consulting with a urologist can help males with CF with incontinence problems.

Gaps in Patient-Provider Communication

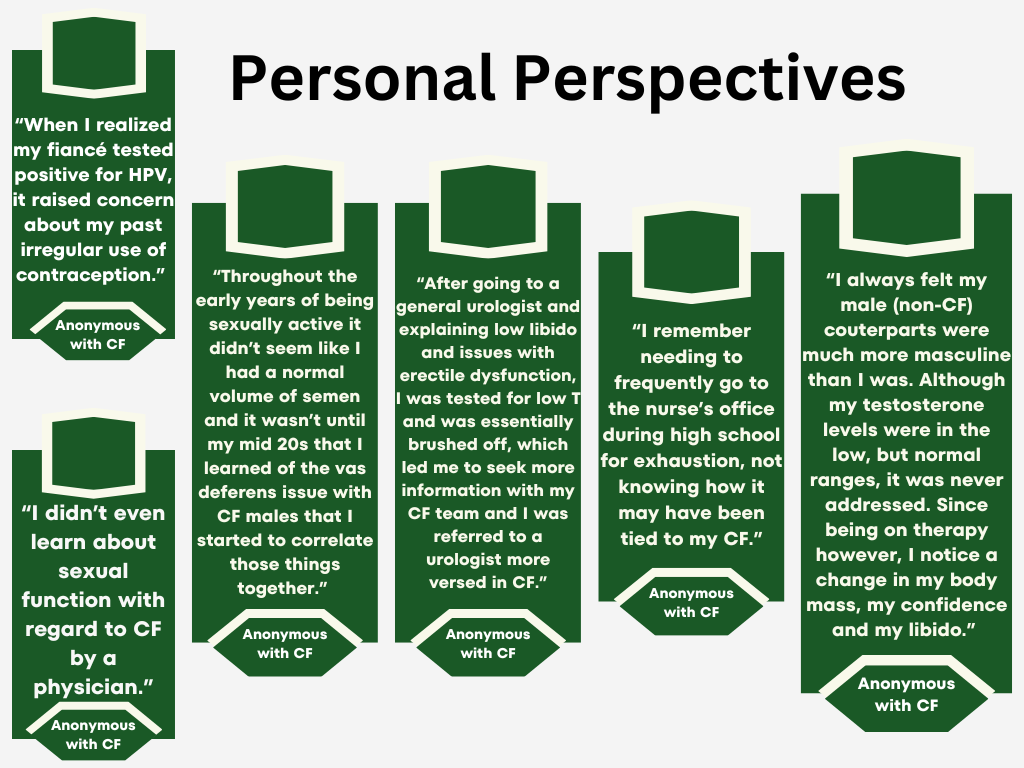

Despite Clarke et al.’s finding that “men with CF endorsed the importance of supportive and open-ended conversations about SRH with their CF care team and their loved ones,” patient-provider conversations about these issues are uncommon.14,15 West et al. found that males with CF are dissatisfied with sexual and reproductive health-related screening and discussions.10 Indeed, because there are no screening guidelines, discussions on male SRH issues are inconsistent, leading to misinformation.18 A paucity of SRH conversations with male patients can lead to misunderstandings about terms and definitions such as infertility, sterility (unable to produce children), and impotence (unable to achieve an erection).14,15 A lack of education can jeopardize males’ health. For instance, male patients often report lower condom use because they do not believe they are fertile and, therefore, do not need to use them to prevent pregnancy.10,21 However, condoms are important to prevent sexually transmitted infections, a topic completely understudied in people with CF.10 Further, although providers often ask their patients if they are sexually active, they rarely follow that question with information about STI testing. Nor does that follow-up include advocating for the use of condoms or queries about sexual function.14

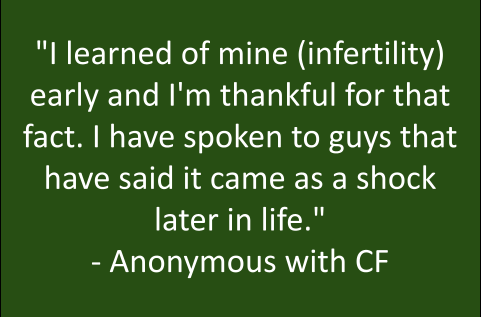

Patients want to learn about potential infertility and their options for parenthood.15 Indeed, over 80% of men with CF want to have children, making it vital to have conversations about fertility early in a patient’s life.15 Early discussions can help avoid the current state of health education, whereby many adult males with CF report only learning about CF and infertility at age 16. While most male patients “felt no distress upon first learning of infertility as adolescents…some describe(d) feelings of sadness” and would have preferred to know earlier in life.15 Others’ distress reported grew as they aged.18 Outside of the US, an Australian study (n=94) found that 22% of its male participants believed that infertility had affected their personal relationships, regardless of age, marital status, or desire for parenthood.18

Patients want to learn about potential infertility and their options for parenthood.15 Indeed, over 80% of men with CF want to have children, making it vital to have conversations about fertility early in a patient’s life.15 Early discussions can help avoid the current state of health education, whereby many adult males with CF report only learning about CF and infertility at age 16. While most male patients “felt no distress upon first learning of infertility as adolescents…some describe(d) feelings of sadness” and would have preferred to know earlier in life.15 Others’ distress reported grew as they aged.18 Outside of the US, an Australian study (n=94) found that 22% of its male participants believed that infertility had affected their personal relationships, regardless of age, marital status, or desire for parenthood.18

Due to these communication gaps, patient-provider discussions about fertility, sexual function, contraception, and other sexually transmitted infection protection, particularly during early adolescence, are vital.15 But “CF providers cite insufficient time and training, as well as personal discomfort” as barriers to initiating discussions around sexual and reproductive health issues in the clinic.15 The existence of these barriers only buttresses the importance of medical education and training on sexual health for providers caring for males with CF.18

Testosterone and Hypogonadism

The hormone testosterone is key for male “sexual, cognitive, and body function and development.”8 It plays a key role in maintaining muscle mass and bone health. Male hypogonadism (the condition where either the testes do not produce enough testosterone, sperm, or both) affects anywhere from 25% to 88% of males with CF. However, the exact number is unknown.2,10,13,15,22,23 This rate is at least 11-fold that of their healthy peers.13,22–24

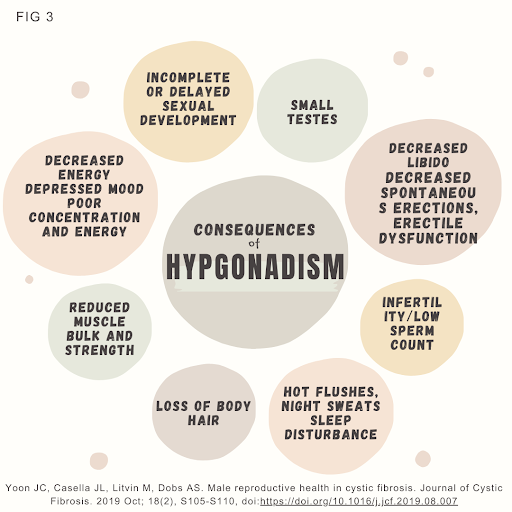

Chronic inflammation, recurrent infections, and regular steroid use are just some of the factors in CF that can lead to hypogonadism.10,15 Delayed puberty in males with CF can also indicate hypogonadism.10 Symptoms for hypogonadism in adults include low libido, decreased muscle mass, low energy levels, mental health changes, and low bone density (See Fig. 3).10,15,24 Patients with CF already have an increased risk of osteoporosis; low T levels might heighten this risk. Indeed, low testosterone should be taken seriously in the CF population as it is related to poor long-term health outcomes in people with chronic diseases, including CF.14,16,22,23

While providers are aware that males with CF have a higher risk of hypogonadism than the general population, no CF-specific screening guidelines for hypogonadism exist. Still, patients with symptoms should be screened. Hypogonadism screening requires a blood sample collected on two separate occasions between 7 am and 9 am (when testosterone levels are at their highest). Since screening for hypogonadism can vary between laboratories, West et al. recommend that patients seek screening at labs participating in the Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) Hormone Standardization Program.10

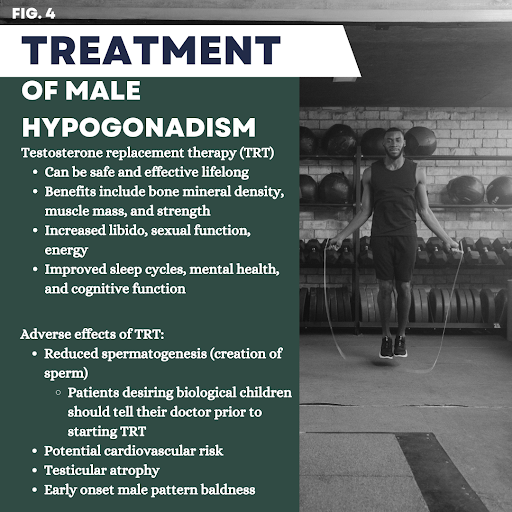

Patients with a positive screen are treated with testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), although TRT is rarely a standalone treatment.2 A comprehensive hormone replacement clinic will likely address the patient’s total hormone picture and make recommendations based on need and health background. According to Campbell et al., “TRT has been found to significantly improve libido, erectile function, sexual satisfaction, and increase muscle mass and bone density, and decrease the risk of osteoporosis, leading to improved physical performance and decreased risk of falls and fractures.”22 In addition, Rosen et al. have reported that TRT could improve quality of life, reduce sexual symptoms, and lessen psychological issues.24

There are different ways to deliver TRT, including testosterone oral supplementation (pills), Testosterone patches, gel/liquid solutions, and injectable Testosterone.25 An evaluation with a medical provider is required to find the right TRT delivery method, and monitoring of testosterone levels is crucial.25

Spermatogenesis and Azoospermia

The production of sperm is called spermatogenesis.6 The testes inside the scrotum produce sperm cells and testosterone. Normal testosterone levels are crucial for proper spermatogenesis.15

An impaired process of spermatogenesis, diagnosed through semen analysis, can negatively impact the quality and quantity of sperm. Though past research finds that males with CF had normal spermatogenesis, more recent reports have found that the CFTR mutation (expressed in sperm) may compromise spermatogenesis.11,15 In addition, because there are no vas deferens in the majority of males with CF, sperm does not reach the ejaculate. Males with CF, therefore, have obstructive azoospermia (lack of sperm in the ejaculate).16 A male with CF’s sperm analysis may, therefore, reveal that the ejaculate “is azoospermic, low volume, acidic, and primarily composed of prostatic fluid,”10 and that also contains “low fructose and low pH.”16

Male Infertility

Male reproductive disorders are the result of sperm production deficiencies or obstruction of the vas deferens.16 The vas deferens are the tubes that carry the sperm from the gonads during ejaculation.

In CF, most males have a congenital absence of the bilateral vas deferens (CABVD). CABVD is the absence or obstruction of both tubes, one from each gonad. Unilateral absence of the vas deferens (CUAVD) is where only one tube is obstructed or absent, leading to some sperm being found in the ejaculate. In CF, CABVD develops in utero due to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) mutation; therefore, researchers do not believe that Highly Effective Modulator Therapy (HEMT) will reverse this condition.15 Gilbert et al. find that “CBAVD is most commonly associated with deltaF508 and R117H mutations in the CFTR gene.”11 For the minority of males with CF who are fertile, the 3849–10 kb C-T mutation seems to play a role.18 Even for people with CF, a CFTR mutation is associated with CABVD. Interestingly, 78% of males without CF but with CBAVD carry at least one copy of a CFTR mutation, and 53% of males without CF but with CBAVD carry two CFTR mutations.11 Males may learn of their CF diagnosis because of their infertility. Others may be CF carriers, infertile, and exhibit no other CF symptoms beyond infertility.16

Infertility, caused by CABVD, occurs in about 95-98% of males with CF.15,16 Not only is there no sperm in the ejaculate, but males with CF may also have a lower volume of ejaculate because of CBAVD.11,14 The diagnosis of male infertility typically occurs in three ways. First, a provider may collect a semen sample. Second, a physical examination of the scrotum can assess the vas deferens’ absence. Third, a scrotal or transrectal ultrasound can confirm the previous methods. According to urologist Dr. Ranjith Ramasamy in his presentation video “Urology for Males with CF,” the best way to diagnose males with CF with infertility is a physical exam.23 The CF clinic can provide a referral to a urologist or male reproductive expert for testing to confirm an infertility diagnosis.

Assistive Reproductive Technology (ART)

For males, discussions of infertility can be difficult to broach with a partner, especially if he/they both desire to pursue parenthood. But, according to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, “sperm production in the testicles is normal in 90 percent of men with CF.”13 With normal sperm production, infertile men with CF men can have their sperm extracted for use in assisted reproductive technology (ART) or stored in a sperm bank.

Assisted Reproductive Technology is a procedure where the sperm is extracted from the male and used to fertilize the egg outside of the mother’s body and is then implanted into the uterine wall. Donor egg or sperm, with or without surrogacy, is another option. ART allows males with CBAVD to have biological children. In vitro fertilization (IVF), a type of ART, requires many sperm. Providers strongly recommend genetic testing and counseling before IVF because males with CF are carriers of the CFTR gene; if they do not want to have a child who is a carrier of (or have) CF, they would need to take steps to avoid it.15

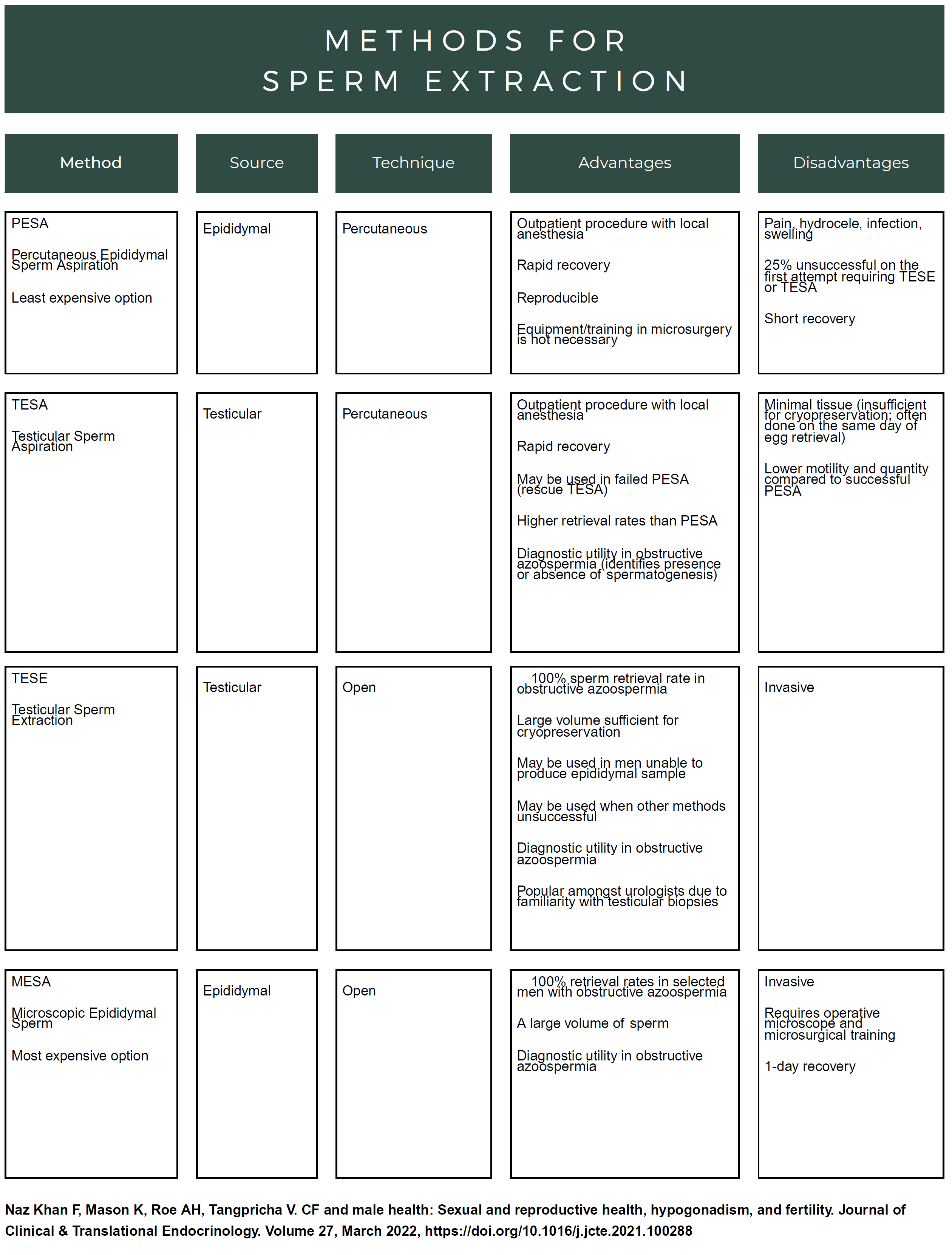

The first step in ART for males with CF is to do either testicular sperm aspiration (TESA), percutaneous epididymal sperm extraction (PESA), or microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration (MESA).15,21 According to Campbell et al., “some studies find that during sperm retrieval, men with CF have lower sperm concentration, decreased sperm motility, decreased bicarbonate sensitivity, and ultimately lower fertilization rates.”22

Sperm retrieval is done using “local anesthesia and a needle attached to a syringe to extract sperm from the testicle or epididymis.”21 According to Meiss, sperm retrieval rates for obstructive azoospermia can be as high as 100%.21 After the sperm is harvested, it can be injected into an egg from a female. This is called intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). ICSI only requires a single sperm for injection and, therefore, is often well-suited for males with CF who experience azoospermia.15 Naz Kahn et al. state that “pregnancy rates after one or more rounds of ICSI are reported to be nearly 63% with approximately 45–75% live births” but note that “despite its fairly high success rate, only a portion of men with CF are aware that fertility treatments are available.”15

Despite fertility treatments’ fairly high success rate, few men with CF seek them. Men with CF need to know they have options and to seek help from a qualified urologist and genetic counselor.

Parenthood

Researchers have found that most people with CF desire parenthood. However, that research is less focused on fatherhood and its impact on males with CF than on females.14,26 Because the US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry does not ask questions on parenthood and reproduction, there is a dearth of information about the number of males with CF who become parents every year.26 The impact of fatherhood on patient outcomes in the US and elsewhere has also been understudied.26

Males with CF are concerned about the effect of CF on their ability to parent, specifically about balancing their healthcare with childcare responsibilities. Males with CF often weigh the physical and emotional toll that their morbidity and mortality would take on their families and how to discuss these issues with their children.

According to Elinor Schwind, a CF genetic counselor who has studied this and other SRH topics, when a parent has CF and would like to pursue parenthood, there are numerous topics for patients to discuss with their partners. In her “Genetic Testing and Counseling Considerations for Males with CF” presentation video, Schwind recommends couples discuss survivorship, the impact of parenting responsibilities, establishing a solid support system, and discussing anticipated lifestyle changes.27 These difficult discussions must also focus on the financial and emotional toll parenthood takes on the individual with CF and/or the household. She suggests that partners review their medical coverage with a clinic social worker before consulting with a urologist and a fertility clinic. Out-of-pocket costs for sperm retrieval, banking sperm, and in-vitro fertilization can be very high, depending upon the state and one’s insurance policy.27

Genetic Counseling

Understanding genetics is an important part of planning for becoming a parent. If a prospective parent has CF, they will pass a CFTR mutation to their child. If a person with CF has a child with a person who is a CFTR carrier, then there is a 50% chance that the child will have CF. Even if the child does not have CF, s/he/they will still be a carrier.

Testing during pregnancy can help indicate if a fetus has CF. A sonogram can monitor the meconium ileus if the couple is a CF carrier. Once the child is born, newborn screening or a sweat test in the first month after birth can diagnose if a newborn has CF.27 Every state provides newborn screening for CF, but not all 50 states administer the same test.

Males with CF who desire to become parents can seek out genetic counseling. Some clinics may have a genetic counselor available, or a referral can be provided. Genetic counseling helps prospective parents understand and adapt to CF’s medical, financial, and psychological impacts on reproduction.27 Genetic counselors promote informed parenthood choices such as adoption, foster care, step-parenting, surrogacy, or assisted reproductive technology.27 CF Clinics and Genetic Counselors advocate genetic screening for members of the CF community, and this is not typically a problem as over 80% of patient attitudes support prenatal screening.28

Genetic counselors possess a wealth of information on genetic sequencing tests. Genetic counselors can help review family history and advocate for specific gene testing. They can review testing costs and insurance coverage options, how long it will take to get test results, what the results mean, and how to best use the information the test provides.28 However, not all genetic screens are equal, resulting in the limitations of identifying some CFTR mutations.27 For instance, the Basic Mutation Panel screens are for 23 CFTR variants, and the Expanded Mutation Panel screens are for larger panels. Prenatal screening tests can also vary by state. Genetic counselors can help interpret results and help guide couples on their parenthood journey.

Sexual Function and Psychosocial Issues

The psycho-social impacts of this disease on men’s sexual and reproductive health are underreported, undiagnosed, and thereby often go untreated. Yet there are many causes for SRH-related mental health distress among males with CF. Because men with CF produce very little ejaculate, they can feel inadequate, which can influence their level of self-esteem.18 Another cause for distress can be found in the prevalence of low testosterone levels, which can cause low libido. Infertility is another reason for mental health distress. Since fatherhood is considered by many men to be a key component of their masculinity, finding out that one is infertile can significantly and negatively impact one’s sense of self.13 It is vital that sexual health needs be addressed in clinics so that men are aware of their treatment options and so that stigma or embarrassment associated with these causes can be reduced.

Conclusion

CF providers should be aware of male sexual development issues in CF. They should also understand the prevalence of psychosocial challenges relating to development and reproduction. Patient-provider discussions should focus on infertility, Assisted Reproductive Technology, condom usage, STI testing, issues of sexual function, and low testosterone, among other topics. While these discussions may provoke unease in providers and patients, they should start as early as adolescence and continue throughout patients’ lifespans. These issues can be managed with specialists in relevant fields, like internal medicine, urology, psychology, and reproductive medicine. Males with CF need to have this SRH information to maintain their mental and physical health. They should seek such information to optimize their well-being.

Resources

- Find a genetic counselor by zip code: www.nsgc.org

- Information about various CFTR variants: www.cftr2.org

- Family Planning and Parenting Series: www.cff.org

- Resolve: The National Infertility Association: www.resolve.org

- CFF Compass Program: 1-844-266-7277

- CFF Foundation: https://www.cff.org/managing-cf/fertility-men-cf

Works Cited

- Sharma M, Leslie S. Azoospermia. In: StatPearls [Internet]; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578191/

- Kumar P, Kumar N, Thakur DS, Patidar A. Male hypogonadism: Symptoms and treatment. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2010;1(3):297-301. doi:10.4103/0110-5558.72420

- Leslie S, Soon-Sutton T, Khan M. Male Infertility. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562258/

- Casey G. Sex hormones and health. Nurs N Z Wellingt NZ 1995. 2017;23(1):24-28.

- Aliouche H. An Overview of Sex Hormones. News Med Life Sci. https://www.news-medical.net/health/An-Overview-Of-Sex-Hormones.aspx

- Suede S, Malik A, Sapra A. Histology, Spermatogenesis. In: StatsPearl [Internet]. StatsPearl Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553142/

- Royfman R, Shah TA, Sindhwani P, Nadiminty N, Avidor-Reiss T. Sterility, an Overlooked Health Condition. Women Basel Switz. 2021;1(1):29-45. doi:10.3390/women1010003

- Galansky LB, Levy JA, Burnett AL. Testosterone and Male Sexual Function. Urol Clin North Am. 2022;49(4):627-635. doi:10.1016/j.ucl.2022.07.006

- Campbell K, Zarli M, Schuppe K, Wong R, Rahman F, Ramasamy R. Sexual and Reproductive Health Among Men With Cystic Fibrosis. Urol Ridgewood NJ. 2023;179:9-15. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.06.017

- West NE, Kazmerski TM, Taylor‐Cousar JL, et al. Optimizing sexual and reproductive health across the lifespan in people with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022;57(S1):S89-S100. doi:10.1002/ppul.25703

- Gilbert L, Johnson S, Stokes S. Sexual and Reproductive Health and Counseling. In: Springer International Publishing AG; 2020:89-104. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-25909-9_9

- Goldsweig B, Kaminski B, Sidhaye A, Blackman SM, Kelly A. Puberty in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:S88-S94. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.013

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Fertility in Men with CF. Accessed July 18, 2023. https://www.cff.org/managing-cf/fertility-men-cf

- Clarke AR, Stransky OM, Bernard M, et al. Men’s sexual and reproductive health in cystic fibrosis in the era of highly effective modulator therapies–A qualitative study. J Cyst Fibros. 2022;21(4):657-661. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2022.02.002

- Naz Khan F, Mason K, Roe AH, Tangpricha V. CF, and male health: Sexual and reproductive health, hypogonadism, and fertility. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2022;27:100288-100288. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100288

- Yoon JC, Casella JL, Litvin M, Dobs AS. Male reproductive health in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:S105-S110. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.007

- Frayman KB, Chin M, Sawyer SM, Bell SC. Sexual and reproductive health in cystic fibrosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26(6):685-695. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000731

- Sawyer SM, Farrant B, Cerritelli B, Wilson J. A survey of sexual and reproductive health in men with cystic fibrosis: new challenges for adolescent and adult services. Thorax. 2005;60(4):326-330. doi:10.1136/thx.2004.027599

- Whitehead W. The Prevalence and Risk of Fecal Incontinence in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis: Nothing to Sneeze At. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(4):818-819. doi:10.1007/s10620-018-4970-2

- Frayman KB, Kazmerski TM, Sawyer SM. A systematic review of the prevalence and impact of urinary incontinence in cystic fibrosis. Respirology. 2018;23(1):46-54. doi:10.1111/resp.13125

- Meiss LN, Jain R, Kazmerski TM. Family Planning and Reproductive Health in Cystic Fibrosis. Clin Chest Med. 2022;43(4):811-820. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2022.06.015

- Campbell K, Deebel N, Kohn T, Passarelli R, Velez D, Ramasamy R. Prevalence of Low Testosterone in Men With Cystic Fibrosis and Congenital Bilateral Absence of the Vas Deferens: A Cross-sectional Study Using a Large, Multi-institutional Database. Urol Ridgewood NJ. 2023;182:143-148. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.08.039

- Ramasamy R. Urology for males with CF. Presented at: CFLF virtual meeting; December 7, 2022; Virtual. Accessed June 30, 2023. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1E7r4S1B6WUjGZWvNU-IelGfjOHvs7M6hyUiTHS3WO_g/edit#heading=h.20t2s5yrpdxg

- Rosen RC, Wu F, Behre HM, et al. Quality of Life and Sexual Function Benefits of Long-Term Testosterone Treatment: Longitudinal Results From the Registry of Hypogonadism in Men (RHYME). J Sex Med. 2017;14(9):1104-1115. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.07.004

- Barbonetti A, D’Andrea S, Francavilla S. Testosterone replacement therapy. Androl Oxf. 2020;8(6):1551-1566. doi:10.1111/andr.12774

- Kazmerski TM, Jain R, Lee M, Taylor-Cousar JL. Parenthood impacts short-term health outcomes in people with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2022;21(4):662-668. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2022.02.006

- Langfelder-Schwind E. Genetics with males. Presented at: CFLF Virtual Meeting; September 20, 2022. Accessed June 30, 2023. https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/16-Yh3cXcWsTsNxfsz3AJD0-60cMN1Vicc0_fXfm4Tuc/edit#slide=id.p

- Foil KE, Powers A, Raraigh KS, Wallis K, Southern KW, Salinas D. The increasing challenge of genetic counseling for cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18(2):167-174. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2018.11.014

Free Printable PDF Download

Want a free printable PDF download of this section for your use in clinic? Just give us your name and email address below to open the PDF in a new tab.

This form will not add you to our email list.