Sexual Function

in CF can be affected by medications, lung function, age, CFRD, transplant, and changes in overall health, causing changes in libido, orgasm and sexual well beingCFReSHC CF-SRH Resource Guide by Patients for Providers and Patients

Key

For Providers

For Patients

For Patients and Providers

- Are you satisfied with your sex life and sexual function?

- Have you noticed any changes with your sex drive, pain with intercourse, vaginal dryness or vaginal discharge/odor?

- Have you noticed any changes with sex due to your new medication?

Click Here for additional questions for patient to ask their provider.

- Do any of my medications have side effects related to sexual function? Could they affect my libido? vaginal dryness? e.g. antidepressants or modulators?

- My antidepressants are causing low libido, what other options are available to help my mood?

- Is there someone specialized in sexual health that I could speak to about various issues related to my sexual function?

- I feel stressed that I am unable to enjoy sex, is there a qualified provider or sex therapist you can refer me to?

- How does my CF and CF care affect my sexual health? Does my age affect my sexual health?

Click Here for additional questions for patient to ask their provider.

Human Sexuality and CF

Cystic fibrosis does not diminish sexual desire or the need for intimacy. In fact, sex is a wonderful source of relaxation, pleasure and fulfillment [1]. Humans are sexual beings; therefore, sexual intercourse is a normal part of adulthood.

In a CFReSHC Snap Poll conducted (6/3/20-7/28/20) of women with CF:

- 79.5% of respondents (n=39) believe that CF plays a significant role in their sexual function.

- 32 out of 38 CF women said they would consider seeking the help of a recommended lisenced sex therapist to discuss sexual function.

- 31 out of 40 would be interested in speaking about their sexual function issues with someone at their CF clinic [2].

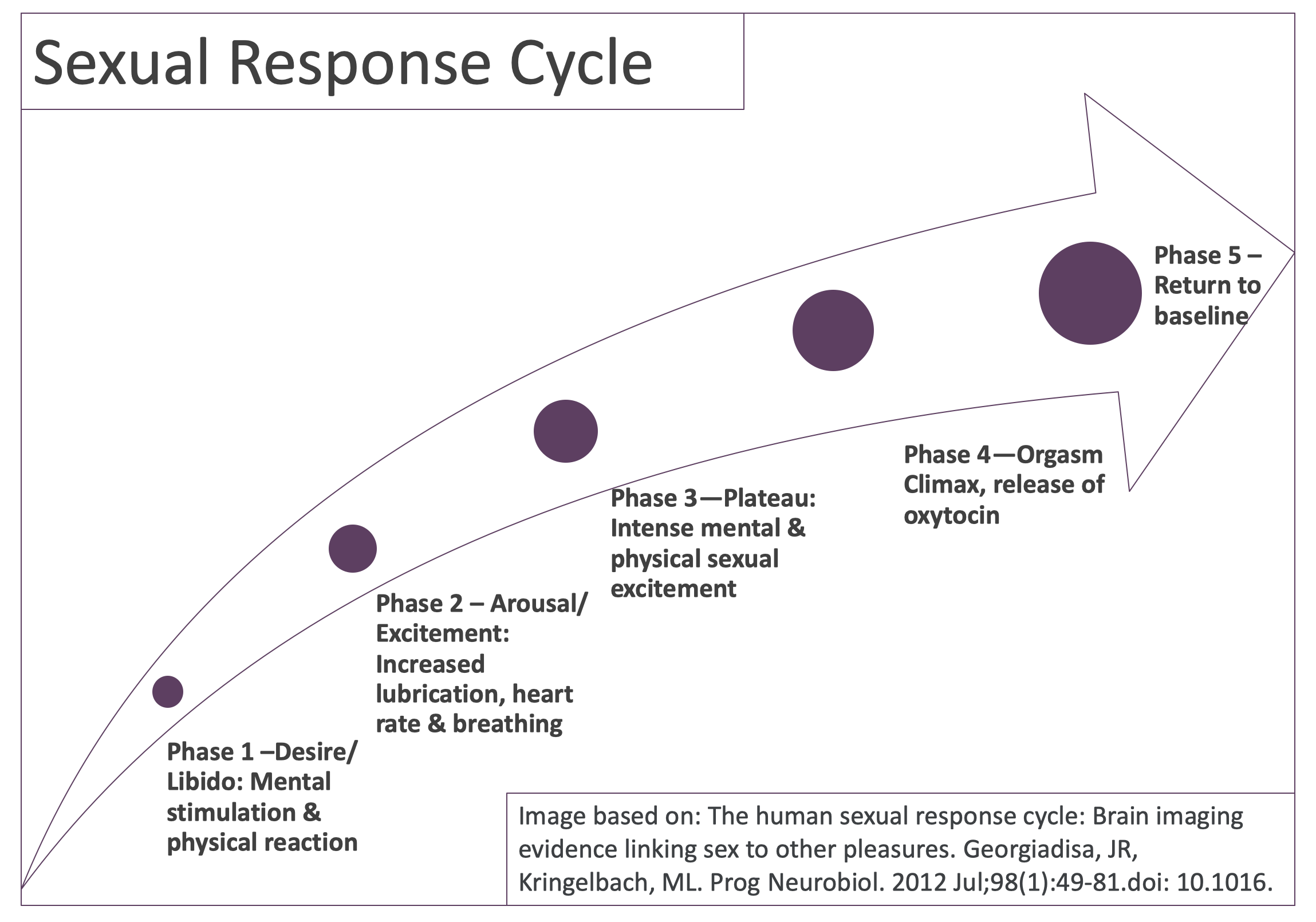

The Sexual Response Cycle

During intimate situations, women with CF will experience some, if not all, of the stages of the sexual response cycle. Not all women, however, experience the same reactions during the sexual response cycle and variation–even individually– in sexual response is common across the lifespan. This is true for women with CF as well.

During Phase One (Desire/Libido: Mental stimulation and physical reaction), issues with low libido and body image impact women with CF. During a CFReSHC Patient Task Force (PTF) Meeting (2/12/2020), attendees expressed concern over low libido. Women shared that low libido may be a side effect of some medications. Illness itself often reduces sex drive, as do fatigue, stress, mental health issues like depression and anxiety, hormonal changes that occur with menopause, and previous negative or abusive sexual experiences. People with CF sometimes worry about the safety of engaging in sexual intercourse post-hospitalization, post- transplant, or while doing IV antibiotic therapy [3]. Complicating these issues, some people with CF often feel critical of their own appearance and have poor sexual-esteem (fear that they are not attractive to their partners) [4].

During Phase Two (Arousal/Excitement: Increased lubrication, heart rate and breathing), lubrication issues can play a significant role for women with CF. Typically, females experience increased lubrication which reduces friction during intercourse, but for those who experience vaginal dryness, introducing lubrication may help them enjoy the encounter. Lubricants that are glycerin-, paraben-, and petrochemical-free can help with thick cervical mucus, vaginismus, dyspareunia, and vaginal dryness [see the Vaginal Health chapter]. Using lubrication before engaging in sex can help prevent chafing, burning, itching, and other kinds of discomfort [4]. But lubricants that contain glycerin (e.g. flavored lubricants) can cause or aggravate vaginal yeast infections and so are not recommended [3]. “Warming” lubricants might burn, making sex more painful [3].

Phase Three (Plateau: Intense mental and physical sexual excitement) is the most intense phase of the sexual response, when physical and mental stimulation increase. In women with CF, issues with recurrent yeast infections, incontinence, flatulence, and hemoptysis can negatively impact response during this phase. Clearly, thick intravaginal creams used to treat yeast infections can be a deterrent to vaginal intercourse. Moreover, fear of leaking urine, passing gas and coughing up blood might prevent a woman with CF from engaging in intimate activities, especially intercourse. Painful intercourse (dyspareunia) can also be a problem for women with CF. In a CFReSHC snap poll, for instance, 45 out of 79 women with CF reported painful intercourse caused by vaginal dryness, vaginismus or vulvodynia [2].

Phase Four (Orgasm: Climax, release of oxytocin) is the shortest phase of the sexual response cycle but it is also the most intense if/when orgasm is achieved. The female orgasm lasts 25-30 seconds but it remains a mystery.

Researchers have tried to disentangle the multifactorial nature of the female orgasm. According to Daniele Mollaioli, et al (2018) the “female orgasm is not yet fully understood and defined because of the great variability in factors, including localization, stimulation techniques, self-image and quality of romantic relationship” [5]. She also found that the other phases–desire, arousal and lubrication– play an important part of the orgasmic function [5].

According to writer Michael Castleman, in Psychology Today: when psychologists and sociologists focus on women’s orgasms they find that relationship happiness increases the likeliness of orgasm only modestly. Sex researchers, conversely, focus on what happens during the interaction where the quality of couples’ lovemaking plays the biggest role in orgasm rates. To be sure, women free from sexual trauma are somewhat more likely to have orgasms [6].

In their 2016 Finland study entitled the “Determinants of Female Sexual Orgasms,” Kontula et al found that increased masturbation or experimentation with different partners did not increase the frequency of orgasm. Rather, emotional and relationship factors were key to promoting orgasm [7].

For those women who achieve orgasm, many experience female ejaculation (approximately 69.23%) [8]. Journalist Adrienne Santos-Longhurst writes that female ejaculate has several unique characteristics:

- it is a thicker, whitish fluid that resembles very diluted milk;

- it contains some of the same components as semen;

- it contains small amounts of creatinine and urea, urine’s primary components;

- it comes from the Skene’s glands, or “the female prostate,” located on the front wall of the vagina, surrounding the urethra; and

- it can happen outside of orgasm through G-spot stimulation [8].

Furthermore, it is possible to experience both a vaginal and clitoral orgasm where both the external and internal clitoris is stimulated [9].

Even though most attention is paid to those who can achieve orgasm, there are also plenty of females, about 50%, that rarely or never reach an orgasm [11]. This inability to achieve orgasm is called anorgasmia; having a delayed and/or less intense orgasm is called female orgasmic disorder. According to Kontula, women can be and are sexually satisfied even without achieving an orgasm. However, based on previous sex surveys, these researchers found that the “most important single predictor of sexual satisfaction for women is without a doubt the orgasm” [8].Yet for the 38% of women who did not experience an orgasm during their latest intercourse, they found that these women felt that intercourse was still pleasant [8].

Phase Five (Return to Baseline) is when mental and physical stimulation return to their baseline status. Breathing eases and fatigue can become apparent.

Body Image and Sexual Function:

Many women with CF have body image issues due to being underweight or overweight, having scars from medical treatments and procedures, using oxygen, infusing IV therapy, and/or having feeding tubes [See the Body Image chapter]. Lung transplant survivors commonly struggle with their body image post-transplant, with concerns about “moon facies” (the round face shape that develops from chronic steroid use), acne, bruising, increased body hair, hair loss on the scalp, and other iatrogenic side effects (side effects of medical treatment). These body image concerns can decrease their sexual-esteem. Women may believe these external markers of disease make them unattractive to their partners, even when their partners are very attracted to them. Feeling less attractive, regardless of the reason, can negatively impact one’s sexual function, including interest in intimacy.

Remedies and Treatments for Sexual Function Issues

Lemon Balm for Low Libido:

In a 2018 Iranian study, researchers gave 43 women without CF who were experiencing low sexual desire (female sexual interest/arousal disorder) a placebo or 1g of lemon balm. The investigators instructed their participants to take the lemon balm an hour after breakfast and an hour after dinner for 4 weeks [4]. They found that women taking lemon balm saw a significant increase in desire as compared to those taking the placebo. Participants also self-reported a significant improvement in the Female Sexual Function Index Score (FSFI), a 19-item self-report inventory designed to assess female sexual function. The FSFI consists of six domains: desire [two items], arousal [four items], lubrication [four items], and orgasm, satisfaction, pain [three items each]. Women in the lemon balm group had intercourse more than twice as often as their placebo counterparts [4]. In addition, 81.8% of the lemon balm group was highly or very highly satisfied with the treatment; only 4.8% of the placebo group reported that they were highly satisfied [4]. This study could be performed on a group of women with CF to see if similar results could be achieved.

Partner communication: During her presentation at the June 3, 2020 PTF meeting, sex therapist Phronsie Springer LCSW, CST emphasized that partner communication is vital to ensuring pleasurable sexual encounters. While women often value their partner’s climax over their own, factors that contribute to achieving orgasm include concentrating on the encounter, having an emotionally stable relationship, and having a partner employ certain techniques [10]. Kontula et al confirm Springer’s observations. In their study on female sexual orgasms they found that mental and relationship variables, such as desire, sexual self-esteem, and open communication with partner(s), increases orgasms [7].

Sex Toys:

Taboos about sex toys and other sex aids to increase pleasure are decreasing as more people use them. Fears around using toys still exist, however. According to licensed marriage and family therapist at AdamandEve.com, Dr. Kat Van Kirk, Ph.D., there is a misconception that using toys means your partner is ineffective or is being replaced to achieve an orgasm [10]. But in a 2016 study on sex toys, David Frederick, Ph.D., found that many satisfied partners used multiple modes to increase pleasure, including toys, showering together, trying new positions and scheduling sex [10]. Still, there are several recommendations that remain pertinent when using toys:

1) use silicone as it has been tested to be safe.

2) wash toys immediately after use for hygienic purposes.

3) clean toys used in the rectum prior to inserting them into the vagina [10].

Other remedies: There are other remedies to address issues relating to sexual function abound as well. These include:

- To help with increased respiratory rates during sex, some women with CF suggest doing a breathing treatment prior to sexual activity to help ease any potential breathing issues.

- To conceal lines, tubes and scars, to help them feel better about themselves, and to improve their sexual-esteem, women with CF can experiment with wearing comfortable clothing and/or sexy lingerie.

- Counseling, sex therapy, and edible marijuana–which is associated with satisfaction is used prior to sex– are still other remedies to address sexual function challenges [9].

Specific Remedies and Treatments for Females with CF

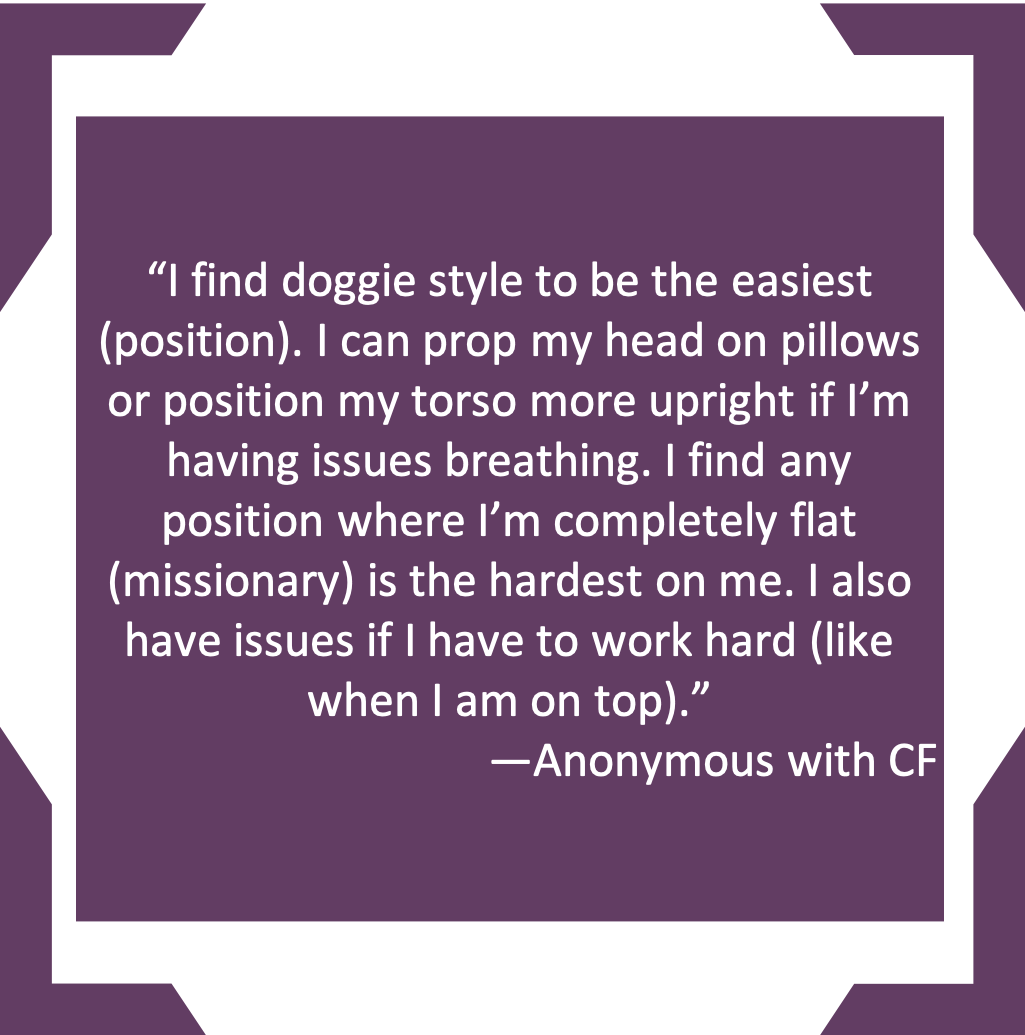

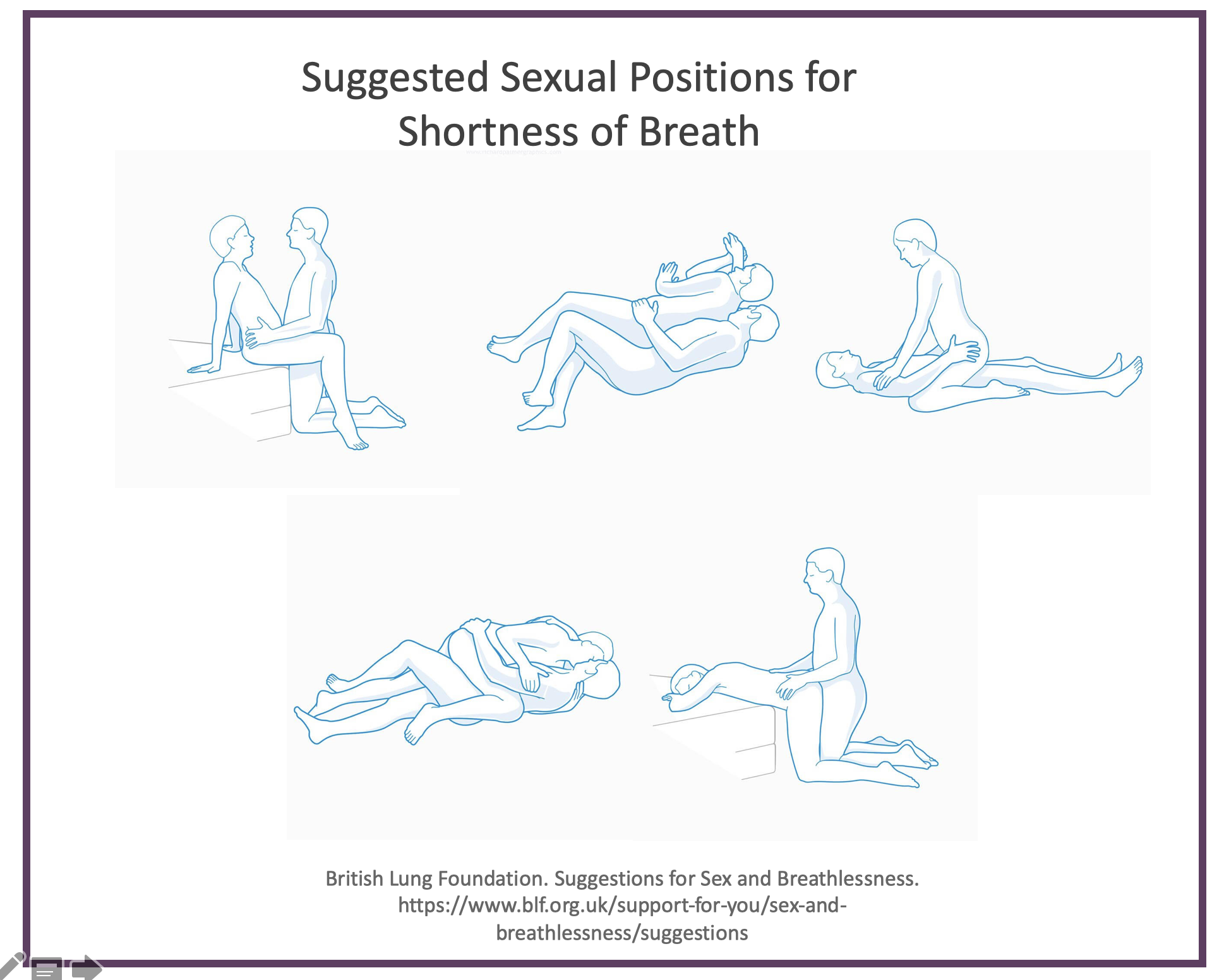

Sexual Positions for Shortness of Breath

Different positions can help women with CF experience a more satisfying sex life. A variety of positions can help women achieve orgasm and can potentially reduce pain and shortness of breath. Since each woman’s vulva, vagina, and cervix are different, trial and error is key to improving sexual function. Sex should be fun, not stressful and it also increases intimacy between partners and induces relaxation. But “like any physical activity, sex can make you get out of breath” [10]. Some experts suggest trying different positions, using pillows to improve comfort, avoiding positions that “put pressure on the chest” and opting for positions that use less energy [10]. The British Lung Foundation suggests the following positions for people with lung conditions:

Post-Transplant Issues

Talking with a provider about diminishing one’s sexual function side effects post-transplant might improve sexual function [4]. Transplant providers typically recommend waiting 4 to 6 weeks after transplant surgery to begin sexual activity. However, female patients may want to discuss other sexual limitations because of CF treatments with a woman’s provider. The key to resuming a satisfactory sexual relationship is to engage in an open and honest discussion with a partner over one’s fears and potential limitations [4].

Sexual Function Disorders

Sexual dysfunction is generally divided into four categories: arousal disorders, orgasm disorders, pain disorders, and disorders of desire. To be considered a sexual dysfunction, the issue must occur frequently, cause distress, and be present for several months.[1] A new 2024 study on the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in females with CF in France showed that females with CF have the same rate of sexual dysfunction as the general population. Thirty percent of the study’s female participants reported sexual dysfunctions in its quality of life survey; participants did not report, however, that these disorders negatively affected the primary quality of life domains substantially.[2] The same percentage reported the combined issues of urinary tract infections, bowel disorders, vaginal yeast infections, and a history of severe pulmonary disease.[2] The study found no association between sexual dysfunction and BMI, age, diabetes, FEV₁, giving birth, or stress incontinence in females.[2] Fecal incontinence, found in 64% of female participants, contributes to severe sexual dysfunction, particularly orgasm and sexual satisfaction disorders; urinary incontinence does not.[2] Women with CF experience shame and embarrassment from fecal incontinence, which may influence females’ libido. The researchers found that desire and pain were the two most impacted features of sexual function in French women with CF. Issues with the pelvic floor due to years of coughing can lead to genital or pelvic pain during intercourse in females with CF. Affected females can be treated with pelvic floor rehabilitation and can use lubricants to address this pain.[2]

Vaginismus

Psychologist Thippeswamy Harish (2011) writes that vaginismus is considered the most prevalent female psychosexual dysfunction, but the exact prevalence is unknown. Some sexual dysfunction clinics propose prevalence rates between 5-17% [11]. Treatments for vaginismus can include: “sex therapy sessions (that) include education, homework assignments and cognitive therapy…relaxation therapy…Botulinum toxin injection…hypnosis…graded insertion of fingers, Kegel exercises,” but a lack of randomized control trials on treatment options means that data is lacking for their success rates [11]. Other treatments that might help include vaginal dilators, which are often sold online. But without reliable data, women may have to select the best-suited treatment option based upon personal testimonies alone.

Vulvodenia

Thought to impact about 6% of women, vulvodenia can be diagnosed at any age but is often misdiagnosed as vaginismus or physicians miss it because they do not see it frequently [12]. Unfortunately, women who experience vulvodynia or vaginismus might think that painful penetration is “normal;” others might believe that pain and burning is a symptom of a vaginal yeast infection [12].

Vulvodenia negatively impacts a patient’s physical and mental quality of life [12]. Since misdiagnosis can lead to extensive testing and frustration, physicians should refer patients to a pelvic floor specialist or an experienced provider who knows how to diagnose and treat vulvovaginal diseases.

Mental Health, Modulator Therapy, and Sexual Function

There are many mental health issues that women with CF can face when they experience sexual dysfunction disorders. Women can worry about disappointing their partner, which can take a toll emotionally. Others can face body image issues that may affect their sexual function. For instance, some females can become embarrassed about being naked in front of their partner if they have a port. They may feel worried when the port is accessed, leading to hesitations about engaging in sexual intercourse.

Mental health concerns while taking modulator therapy:

Patients with CF have reported many adverse mental health effects of modulator therapy. These effects derive from a rapid change of health, an uncertain future, anxiety, changes to one’s identity, and difficulties with communicating with a patient’s CF team.[9] It is unknown if modulator therapy can cause problems with libido, but this may be a research question that would be worthy of study. Removing modulator therapy may cause changes to one’s identity and other side effects, including possible impacts on mental health.[9] Similarly, providers should be alert to adverse mental health effects for people with CF who are ineligible for modulator therapy.[10] These concerns may also influence a patient’s sex life and desire.

The side effects of HEMT vary for each patient. Still, drug-to-drug interactions, the impacts of HEMT on the brain, physiological changes from HEMT use, and the psychological/existential effects that arise from taking life-altering medications can potentially cause the reported mental health effects of HEMT.[11–13] Clinicians are currently recommending dose adjustments for patients who experience mental health side effects of HEMT.[14, 15] We also know that researchers have observed differences between PwCF on psychiatric medicines before starting HEMT and those who are not on these medicines. Zhang et al. reported, for instance, that:

No significant changes in average PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores were found after Trikafta initiation. [But] A quarter of patients required a change in psychiatric medications, and significant differences in depression and anxiety scores were found between patients with a change in psychiatric medications and those not prescribed medications. Twenty-three percent of patients reported sleep issues after starting Trikafta.[16]

CF-SRH Communication, Information and Care Management Needs

Young women

While all women with CF are sexual beings, their sexual health is not a priority topic during clinic visits. In “Cystic Fibrosis Through a Female Perspective,” Johannesson et al revealed that pubescent girls with CF experienced problems with destructive behavior because of thoughts about dying prematurely, secret worries over delayed puberty, and poorly received information about puberty and fertility [13]. These researchers also found that adolescent girls with CF avoided close relationships with the opposite sex [13]. While parenting and fertility issues are equally important for men and women with cystic fibrosis, many patients do not find out what they want to know by discussing issues with their healthcare providers [14].

In a 2003 study exploring the availability and provision of sexual health information for teenage girls with Cystic Fibrosis, females used their parents as the first source of information while parents looked to the CF doctor as the key resource for information about this topic [13]. Overall, however, few patients had spoken to their doctor about issues relating to their sexual health, despite the fact that 96% requested more information [13]. Mothers of girls with CF were interested in receiving this information before their child reached puberty; young women/women themselves requested it throughout the lifespan [15]. Kazmerski and her colleagues found differences between young women with CF and their healthy peers. For instance:

- 10% fewer women with CF reported having had vaginal sex with a male partner compared to 66% of U.S. women (p = 0.55).

- Women with CF were less likely to have ever used contraception (55% vs. 74%, p = 0.0001)

- Fewer had been tested for sexually transmitted infections in the past year (19% vs. 34%, p = 0.001) compared to the general population

- Females with CF do experience sexual health issues including 16% urinary incontinence, 16% sexual dysfunction, and 49% yeast infections [16].

Young patients with Cystic Fibrosis are not alone in lacking this sort of care management. Citing sexual and reproductive health issues as a key clinical management issue for adolescents with CF, Sargent suggests that providers should assess these patients during regular check-ups, during which time they typically address adolescents’ psychosocial needs [17]. Across several life-limiting conditions, providers who take a history of adolescent participants’ sexual health (n = 25) do not do so frequently, suggesting the need to remedy this gap in adolescent clinical care writ large [17].

Adult Women

In 2018, Norris et al published a study about sex education for people with CF. They found that adults with CF frequently experience sexual problems. Furthermore, unmarried people with CF experience an increased level of sexual dissatisfaction in their lives [19]. Consistent with Norris’ findings, Pfeffer et al showed that adults with Cystic Fibrosis report problems with sexuality, platonic relationships, and independence [18].

Beyond research, better patient-provider communication around these issues is also needed. Because of barriers to shared communication about these issues, Norris et al recommended that care providers should initiate discussions with their patients about SRH issues. Written information and dialogue devoid of medical jargon are beneficial modes of communication [19].

Peer to Peer Advice

- The following lubricants are all glycerin, paraben, and petrochemical free and have been tried by CFReSHC female patient-partners with positive results:

| Good Clean Love 95% Organic Almost Naked Personal Lube | Wet Organics – Aloe-based lubricant is 100% natural |

| Sylk – Eco-friendly lubricant that mimics your body’s natural lubricant | 100% Almond Oil |

| Sustain Natural |

Suggested Sites: Babeland.com GoodVibes.com |

- Make sure to urinate before and after sexual intercourse to reduce the chance of getting a UTI and/or yeast infection.

- Look at your vulva/vagina with a mirror to get to know your body.

- Masturbation helps you learn about your body, what you like and do not like. This helps you learn how your body responds sexually, (e.g. clitoral stimulation), in order to have an open and honest conversation with your partner about your sexual needs.

- Avoid medications targeted to treat female sexual dysfunction because there is no research indicating their effectiveness. Nonetheless, pharmaceutical executives continue to hype the possibility of a “pink Viagra” because the potential market is estimated to exceed $2 billion annually [20].

Works Cited

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD) n.d. h. Accessed June 5, 2024. https://www.who.int/standa rds/classifications/classification-of-diseases

- Ramel S, Gueganton L, Nowak E, et al. Sexual dysfunction in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. Published online 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2024.04.011

- Rousset-Jablonski C, Reynaud Q, Nove-Josserand R, et al. High proportion of abnormal pap smear tests and cervical dysplasia in women with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;221:40-45. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.12.005

- West NE, Kazmerski TM, Taylor‐Cousar JL, et al. Optimizing sexual and reproductive health across the lifespan in people with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2022;57(S1):S89-S100. doi:10.1002/ppul.25703

- Roe AH, Merjaneh L, Oxman R, Hughan KS. Gynecologic health care for females with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2021;26:100277. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100277

- Malouf MA, Hopkins PM, Singleton L, Chhajed PN, Plit ML, Glanville AR. Sexual health issues after lung transplantation: importance of cervical screening. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2004;23(7):894-897. doi:10.1016/j.healun.2003.07.018

- Jain R, Taylor-Cousar J. Fertility, Pregnancy, and Lactation Considerations for Women with CF in the CFTR Modulator Era. J Pers Med. 2021;11(5):418. doi:10.3390/jpm11050418

- O’Connor KE, Goodwin DL, NeSmith A, et al. Elexacafator/tezacaftor/ivacaftor resolves subfertility in females with CF: A two-center case series. J Cyst Fibros J Cyst Fibros. 2021;20(3):399-401. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2020.12.011

- Aspinall SA, Mackintosh KA, Hill DM, Cope B, McNarry MA. Evaluating the Effect of Kaftrio on Perspectives of Health and Wellbeing in Individuals with Cystic Fibrosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(10):6114. doi:10.3390/ijerph19106114

- Allen L, Allen L, Carr SB, et al. Future therapies for cystic fibrosis. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):693. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36244-2

- Sher Y. Mental Health and Concerns in the Era of Highly Effective Modulator Therapies. Presented at: March 2023; Stanford Lecture Series.

- Talwalkar JS, Koff JL, Lee HB, Britto CJ, Mulenos AM, Georgiopoulos AM. Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator Modulators: Implications for the Management of Depression and Anxiety in Cystic Fibrosis. Psychosom Wash DC. 2017;58(4):343-354. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2017.04.001

- McKinzie CJ, Goralski JL, Noah TL, Retsch-Bogart GZ, Prieur MB. Worsening anxiety and depression after initiation of lumacaftor/ivacaftor combination therapy in adolescent females with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16(4):525-527. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2017.05.008

- Spoletini G, Gillgrass L, Pollard K, et al. Dose adjustments of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in response to mental health side effects in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2022;21(6):1061-1065. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2022.05.001

- Dagenais, Renée V. E., et al. “Real-World Safety of CFTR Modulators in the Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Clinical Medicine, vol. 10, no. 1, 2020, pp. 23-, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10010023.

- Zhang L, Albon D, Jones M, Bruschwein H. Impact of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on depression and anxiety in cystic fibrosis. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2022;16:17534666221144211. doi:10.1177/17534666221144211.

Free Printable PDF Download

Want a free printable PDF download of this section for your use in clinic? Just give us your name and email address below to get your download link. This will not add you to our email list.