Body Image

The subjective picture or mental image of one’s own body established both by self-observations and by noting the reactions of othersCFReSHC CF-SRH Resource Guide by Patients for Providers and Patients

In this section:

- Introduction

- Priority Questions

- Unique Concerns

- BMI

- Low Body Weight

- Higher Body Weight

- Disordered Eating

- Patient Care Impacts

- Post-Transplant

- CFTR Modulators

- Recommendations from Patients for Providers

- Study Insights

- Managing Body Image Disturbance

- Patient Perspective

- Peer-to-Peer Advice

- Resource Links

- Works Cited

Key

For Providers

For Patients

For Patients and Providers

Introduction

As patients with CF live longer with active lifestyles, there is a growing need for CF researchers, care teams, and patients to explore issues that can impact their quality of life. As a construct with multiple dimensions, body image refers to an individual’s feelings, attitudes, behaviors, and perceptions about their body and their appearance [1]. In American culture and society, weight is often thought to be a key factor in a person’s body image, but these two issues are not necessarily correlated; being dissatisfied with one’s weight, for instance, does not necessarily mean that a person is dissatisfied with their body and vice versa [1].

Research on body image in the CF population is growing. Bray’s literature review on gender differences regarding health-related quality of life for adolescents and adults with CF showed that females with CF tend to have a more positive body image compared to their male counterparts, despite their lower BMI, weight and height. They also found that females with CF generally prefer a low body weight and believe that being thin is attractive, despite the fact that such cultural norms and personal preferences may compromise their overall survival [2]. For their part, Helms et al. have revealed that young adults with CF want to talk with their providers about psychosocial and preventive care issues, including those associated with body image [3].

- Do you have concerns about your body image? If so, what are they? Would you like to speak with someone about your concerns?

- Does your body image keep you from doing things you would otherwise enjoy?

- In the past we have discussed a diet high in fat and calories to gain weight. There are new healthier recommendations such as consuming good fats and nutrients to gain lean-muscle mass. Can we discuss this today?

- Since you’ve been taking modulators, have your feelings about your body changed?

To Any Provider

- I’m worried about my weight and my body image. Can we talk about this?

- Can we talk about body composition, rather than BMI?

- Can we talk about my goals for my relationship with my body?

Patient to a Registered Dietitian (Nutritionist)

- I am used to eating a high calorie, high fat diet – what changes do I need to make if I gain more weight than I want to while on CFTR modulators?

- What is considered a healthy weight gain while on a CFTR modulator?

- What is considered a healthy caloric and nutrient intake for a woman of my age and build?

Click Here for additional questions for patient to ask their provider.

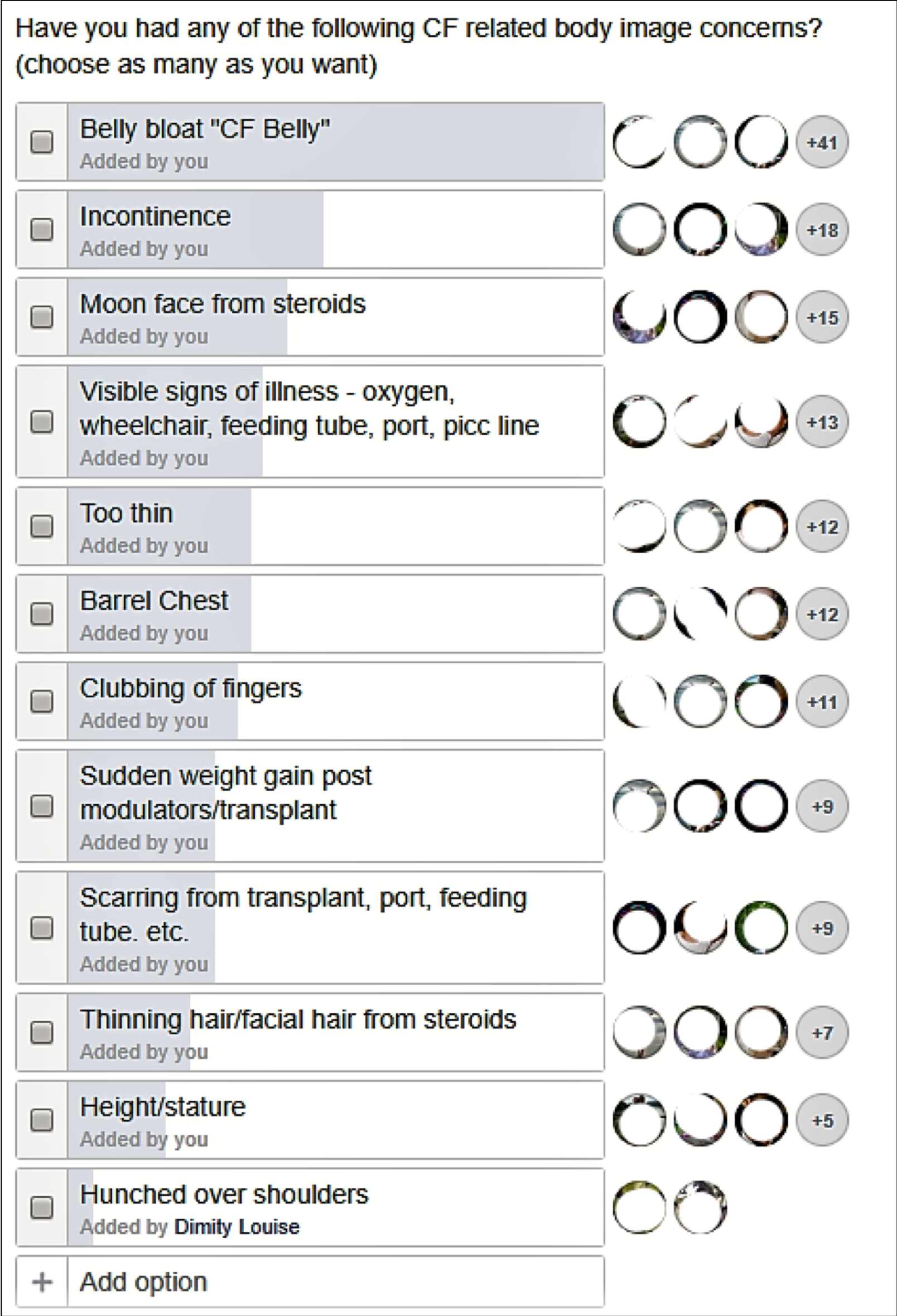

Select Body Image Concerns Unique to People with CF

During a CFReSHC Patient Task Force meeting on body image (3.1.2020), adult women with CF identified the following body image concerns [4]:

| Bloating/distended stomach “CF Belly” | Clubbing of fingers and nails | Salt forming on skin when sweating | Weight gain in general, or related to taking modulators or post-transplant |

| Being thin | Barrel chest | Looking younger | Thinning of hair |

| Having a port, scars, feeding tube, or other medical device | Postural changes – hunched over shoulders from coughing | Deteriorating health (wearing oxygen, using a wheelchair or handicap parking pass, etc.) | Increased facial and/or body hair from certain medications |

| Short stature | Coloring of teeth from certain medications | Sound of voice | Coughing-others may think you are acutely ill |

BMI as a Measure of Nutritional Status and Physical Wellbeing

Stature, weight, and body mass index (BMI) are commonly used in CF clinical care to assess nutritional status. Studies have found an association between low BMI and decreased lung function and mortality. For its part, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF) has offered clinical care guidelines for clinicians to follow to ensure optimal health outcomes. Under this guidance, CF care teams have, for decades, recommended a high calorie diet to their patients [6].

Yet, Sheikh et al have interrogated the nature of this association, noting that researchers have not yet described the extent to which poor nutritional status directly causes poor pulmonary function status. In fact, Sheikh cites a dearth of studies that directly measure body composition in the CF community. Rather, because researchers have specifically shown an association of a higher BMI in the CF population with better pulmonary function (and vice versa), clinicians and researchers have conjectured that this link reflects the influence of lean body mass on muscle strength of the lung [5]. Sheikh points out, however, that BMI in the general population is used as an indicator of “body fatness,” not muscle strength. As such, Sheikh et al reassessed the value and efficacy of BMI as a measure of patients’ nutritional status, citing the particular need instead to study the relationship between fat, muscle stores, and CF health [5]. They conclude that, although BMI may be a fine screening tool, ascertaining patients’ lean body mass may be more helpful than BMI in determining the relationship between body composition and pulmonary function [5].

CFReSHC Patient Task Force (PTF) members have also raised questions about the value of BMI in CF clinical care. At a PTF meeting on Body Image in CF (3.1.2020), attendees wondered, like Sheikh, whether there were other methods to assess the health of a patient’s body, like the proportion of muscle mass, instead of low/high BMI. Many women expressed they felt pressure by their CF care team to reach a certain BMI and to eat high-calorie diets. They noted that such pressure impacts their stress levels, increases anxiety, and influences their body image [4].

Low Body Weight with CF

Malabsorption and undernutrition are well-documented in the CF literature and well known in CF care so our discussion here will be limited. The CFF recommends that patients routinely consult with a CF nutritionist to access the necessary resources to improve their health outcomes [1]. Individualized approaches to nutrition are becoming increasingly necessary in light of changing therapies and new health outcomes for patients with CF.

Nutritionists provide dietary guidance, including information about increased caloric intake to combat low body weight. They also can offer recommendations about the appropriate fat intake to promote the proper absorption of CFTR modulators.

We should be reminded, however, that interventions to treat poor nutritional status, can create important body image concerns. To address these challenges, some providers prescribe medications like Megace™ (Megestrol), Marinol™(dronabinol), or Remeron™ (Mirtazapine) as appetite stimulants. Megestrol is a progestin originally developed as a form of birth control. Dronabinol is a man-made form of cannabis. Mirtazapine is an antidepressant. Depo-ProveraⓇ may also help women gain weight [6].

Yet, when a woman becomes preoccupied with intense dietary regimens or other interventions to address undernutrition, her mental and physical health, including lowered self-esteem and body satisfaction, may be adversely affected [1,2].

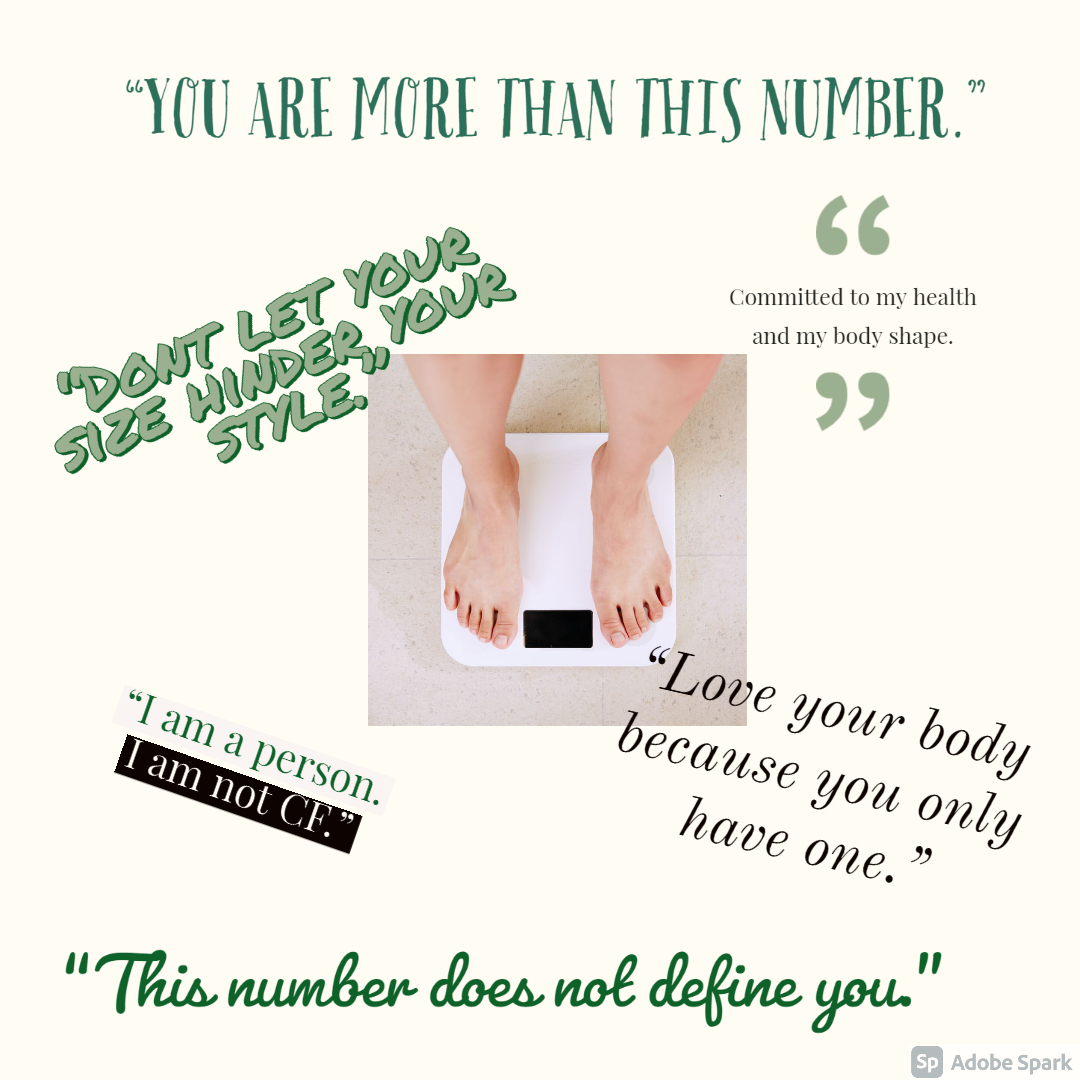

Higher Body Weight with CF

Not every CF patient has a low BMI; even before CFTR modulator therapy, overnutrition existed in the CF community. Improved therapies and interventions, like pancreatic enzymes and nutritional augmentation, helped the weight and nutritional levels of CF patients. With modulator therapy, the incidence of higher body weight has grown. Citing Washington University Adult Center 2019 data, Litvin, for instance, states that almost a fifth of this center’s patients had higher body weight; 55.6% of this group were pancreatic insufficient [7]. Harindhanavudhi’s study of the adult patient population (n= 484) at the University of Minnesota CF center (2015-2017) showed that a fourth of the patients had higher body weight; individuals in this category were more likely to be male, older, have a late diagnosis, pancreatic sufficiency, and “more severe” genotypes” [8].

Whatever the cause (enzymes, CFTR modulators, lifestyle, genetics or another reasons), people with CF who have a high body weight are at risk of acquiring associated health issues, like CF-Related Diabetes, hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea [7]. On the other hand, pulmonary status may improve. Harindhanavudhi’s study suggests that higher body weight was associated with improved pulmonary function and a lower risk of acute pulmonary exacerbation [8].

In terms of body image and weight gain, Bray’s work points to some body dysmorphia for women who believe they are overweight. Females with CF in her study who thought they had a higher BMI tended to restrict calories to a greater extent than healthy peers, despite their actual need for greater caloric intake [1,2]. Clearly, assessing eating behaviors and their impact on body image in CF is warranted for both the clinical encounter and for research.

Higher body weight can impact a sense of identity and belonging, with some patients noting that they did not feel like they “belong” in the CF community because they had different experiences with food and their bodies.[1] For instance, in their article about perceptions and experiences with food and eating in patients with CF, Barrett et al quote a patient who stated, “But I also think being obese is unusual in CF because I sit in a CF clinic and almost everybody is so slim, so many struggle with it (underweight issues) and I feel bad for focusing on it as sometimes it is a luxury of some kind that other CF patients don’t have.”[1]

It remains to be seen how the picture of higher body weight amongst adult patients with CF changes and more studies are needed to discern trends, mechanisms, and outcomes. But the changing profile of weight and body image concerns amongst adults with CF necessitates that care teams adapt their recommendations. Providers need to reevaluate and adjust “caloric goals and diet quality” at every clinic visit; they need to look at nutrition and not just weight. Future guidelines should “address not only caloric targets for patients with CF but also the recommended appropriate micro/macronutrient content of food”[6]. Providers should also monitor patients with weight gain for hypertension, negative body image, and emotional status [9]. Moreover, continued research efforts should assess a patient’s weight gain and its impact upon body image and quality of life.

Patients Perspectives and Behaviors

Barrett et al found that as people with CF age, they can become more more conscious of monitoring their weight and how their body looks. They include patient narratives about people reducing their intake of sugars or fatty foods to maintain their health or an ideal weight and a certain body shape.[1]

Body Image and Disordered Eating

Like other chronic disease populations, intense attention to dietary regimens, nutrition and weight in CF care and in patients’ daily lives can lead to disordered eating patterns [2]. Influences on CF adolescent and adult experiences with food and food choice, and how those intersect with body image, include past and present scrutiny of how and when they eat, what they eat, or if they have faced having a feeding tube to promote weight gain. These experiences are often fraught.[1–4] Even older patients who can care for themselves find that their bodies and food intake continue to be monitored by friends, relatives, and partners.[1]

Abbott et al. found individuals with CF, for instance, often experience increased pressure to eat more and this pressure may lower self-esteem and body satisfaction [1]. Bray et al. remark that females with CF with a lower BMI and a lower self-esteem reported more dieting behaviors [6]. Disordered eating practices can include:

- atypical eating disorder behaviors (e.g. spitting out chewed foods, food avoidance, a preoccupation with food, and bulimic tendencies)

- bodily function distortions relating to gastrointestinal function (e.g. feeling bloated due to medication)

- a misuse of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy [2].

Researchers have shown that patients who receive enteral tube feeding were:

- less satisfied with their body image.

- reported lower self-esteem.

- felt they had a poorer quality of life [10].

Whether people with CF develop eating disorders or not, external and self-scrutiny of eating often means that people with CF interact with food clinically or mechanically.[1] Yet Kass et al found that though a majority of CF providers feel it crucial to screen for disordered eating and body image, they did not feel competent to do so.[5] Gaps in such patient care need to be addressed.

Young adults with CF who feel they have low weight are more likely to take food supplements to improve their health and nutritional status. Those who have body dysmorphia are less likely to do so [3]. Perceptions and behaviors surrounding body image and eating can change when a patient takes part in nutritional interventions. A patient may:

- become more aware of her actual BMI.

- engage in fewer disordered eating behaviors.

- be less preoccupied with food.

- diet less frequently.

Body Image on Patient Care

Growing up, I was always underweight. My doctors were always telling me I needed to gain, and that if I gained my PFTs would go up too. Almost every night at dinner, my mom would tell me to eat more, often teasing me about it. When I was in high school I had to take high doses of prednisone. I hated that my mom and doctors were still telling me to gain weight, even as I put on 20lbs of water weight and got moon cheeks. I didn’t fit in my jeans anymore. I was so upset about it, I started throwing up in the shower after dinner. I felt like I couldn’t talk to my team about hating the prednisone weight. To this day I have never told anyone on my care team or my family. Thankfully going off prednisone and starting college ended my bulimia.

Anonymous with CF

Mental Health: The Impact of Body Image on Patient Care

Though common patterns regarding body image exist amongst females with CF, individual differences play a key role. Clearly, not all patients with a specific condition manifest the same body image [9]. Some women may perceive their body image as positive (e.g. “being thin”) while others may note negative perceptions (e.g. disliking their body because of weight gain/loss or scarring from medical interventions.).

A patient’s response to illness is affected by many variables, including how she feels, looks, thinks, and the level of support she has from medical providers, CF peers, family, and friends. Experiences of chronic illness, like CF, often include changes in physical appearance, body function, and body integrity, as well as medical treatments, all of which shape a person’s ideas about their body [11].

Peer pressure, Western culture’s fascination with thinness, and ideas about fashion can also affect how women with CF view their body and can impact their self-esteem. Sadly, negative verbal feedback from peers, parents, and/or providers can also harm a person’s self-perception. Given these pressures and norms, women with CF can experience appearance-related distress. This occurs when physical indicators are a constant reminder of having a disease, or when a woman notices a change in her appearance. Distress can also occur when there are functional changes for a woman with CF, like a loss of lung function that reduces her ability to be physically active, or a change in bowel habits that impacts her schedule and her ability to leave her home. The speed with which these changes occur can also be a factor in causing distress, as it affects patients’ ability to accommodate the change [11].

Body image concerns and practices are very important issues in the lives of female adolescents and adults with CF. Sexually active women have noted trouble in their intimate relationships due to feeling less attractive to their partner [see the Sexual Function chapter in this guide]. Responses to illness and body image concerns can manifest depression, anxiety, and negative behaviors, such as withdrawing from life, becoming noncompliant with prescribed treatment regimes, or exhibiting aggressive and/or retaliatory behavior [9].

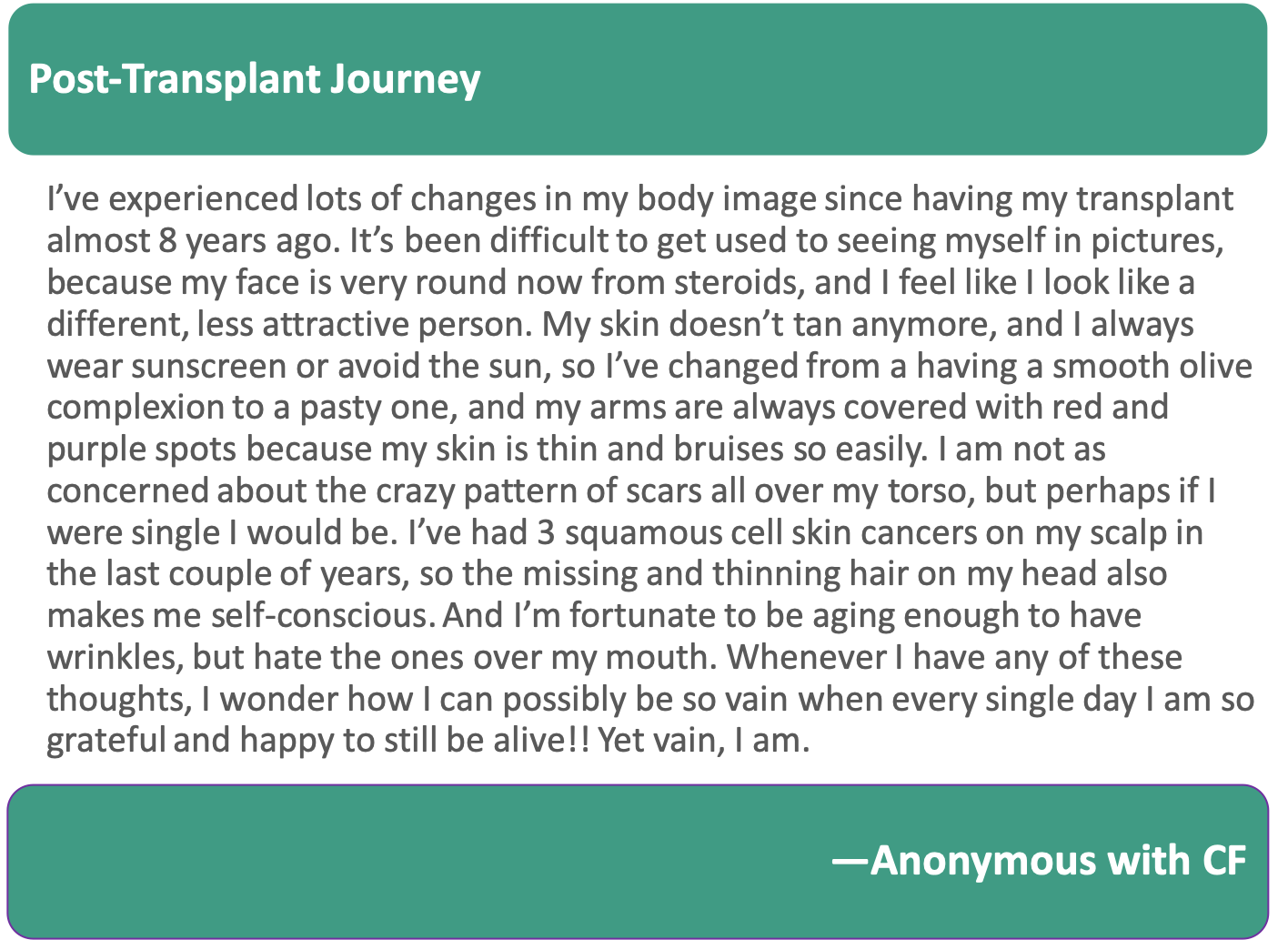

Body Image Post-Transplant

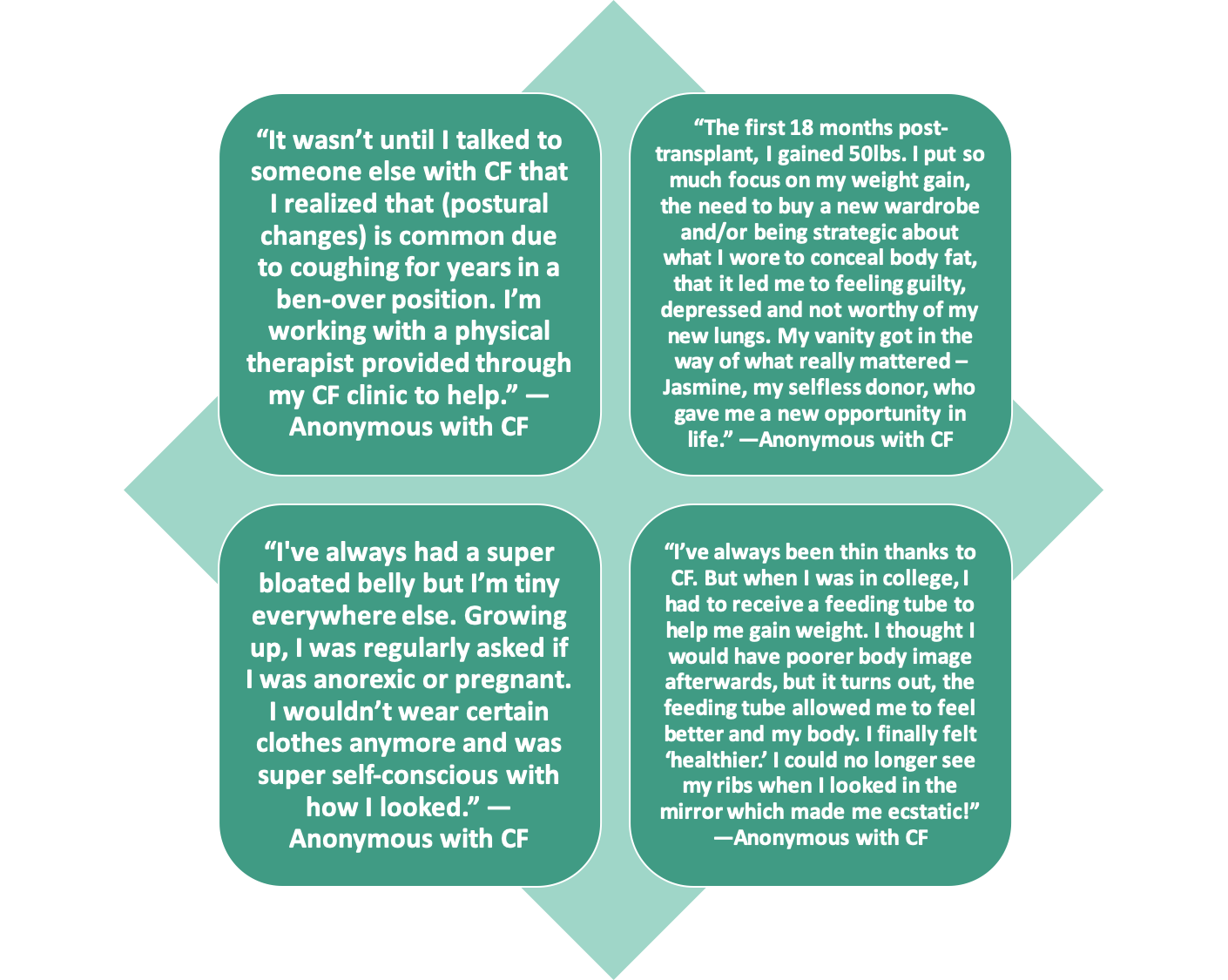

Many women with CF who have undergone a transplant confront changes to their body, inside and out. Indeed, the transplantation process can impact body image in very significant ways. Oftentimes, women with CF find themselves unprepared for these changes since they have overwhelmingly focused on the immediate health benefits of transplantation [10].

However, visible physical changes to one’s body can also impact one’s body image. In transplant, there are numerous such changes. The operation itself involves scarring. The steroids patients must take post-operatively can cause facial swelling (“moon face”) and increased appetite. Many women fight to put on weight pre-transplant so when they can gain weight post-transplant, they may see it as a huge positive in their lives. Since transplant can improve appetites, women might find they can enjoy food once again and can rely on ‘real’ food rather than supplements and overnight feeds, which can boost their morale [11]. Lastly, there are a variety of side effects to new transplant medications. Some immunosuppressants increase hair growth all over the body, which can be a particularly difficult side-effect for women to cope with [12]. Immunosuppressant drugs that are taken after transplant can also cause hair to thin. Tremors are another side-effect of transplant medications, though this does tend to improve with time and does not affect everyone [10]. While our society may over-exaggerate the need to uphold beauty norms, feeling good about oneself can make adjusting to transplantation easier [12].

Body Image in the Age of CFTR Modulators

In their pamphlet on body image and CF, Didsbury et al include several narratives by patients in Britain. One female’s story relays that her team’s delight when she started to gain weight but her dissatisfaction when she looked in the mirror. She noticed her stomach and, compared to her teenage and young adult stages of life, she had difficulty accepting her new body shape. Another woman’s story the pamphlet includes deals with both the body image issues weight gain brings on for her, but also the recognition that such gain prevents her admittance to the hospital, which allows her to enjoy her life more.[6]

There are few published studies on weight gain in the CF population post-CFTR modulators. Clinical trial studies show that patients on ivacaftor (the medication found in CFTR modulator therapies like Kalydeco™, Orkambi™, Symdeko™ and Trikafta™), gained weight by week 8 of the trial compared to those on placebo. This finding was true across a range of adolescents, young adults, and older adults [13].

After starting CFTR modulator therapies, women with CF may see significant changes related to body image in three areas: ideas about eating, perceptions about their body, and issues with weight gain [14]. A study exploring weight gain after starting ivacaftor found that patients experience weight gain because of both the increased fat intake that is required with each dose as well as the decreased “resting energy expenditure, improved fat absorption, and reduced gut inflammation”[15]. Acknowledging the pros and cons of modulator usage can help patients adjust to the visual changes they will experience, particularly as it relates to body image.

How Can Healthcare Providers Help with Body Image Concerns?

Recommendations from CFReSHC’s Patient-Partners

Women participating in our Patient Task Force meeting on Body Image recommended that providers and patients have conversations about body image as part of routine clinical care. This dialogue can help patients feel more comfortable with their bodies. CFReSHC patient-partners also felt it important to address the mental and emotional components of body image [3].

Attendees at the CFReSHC body image meeting wanted their CF providers to support and comfort them when discussing this topic. Such support, they believe, will enable patients and providers to have open and honest communication about sensitive topics like body image. Some patients also expressed the desire to speak with their primary health care provider or with a psychosocial specialist about their body image concerns [3]. Furthermore, some of our patient-partners expressed a preference for discussing body image separately from pulmonary and nutritional discussions in the CF clinic. Patients may find discussing body image difficult to do with their CF provider, especially when their own health or weight goals differ from those of the medical team (e.g. feeling satisfied with themselves at a lower BMI than their medical team’s recommendation, conflicting opinions about g-tubes, etc.) [3].

These women’s insights reveal that discussing body image is a fraught task, one that should be undertaken by providers with care and with various approaches, depending upon the individual. Acknowledging that CF providers may lack experience in having these conversations, patient-partners expressed uncertainty about how best to structure this dialogue [3].

Perhaps when a patient is struggling with adherence to their CF regimen or engages in few social interactions, a provider can assess and address any existing body image issues and/or refer the patient to a CF social worker or mental health provider for further evaluation and help. Through that process, she may improve her health behaviors and doctor-patient communication may improve [10]. If a patient is not taking a medication as prescribed in order to avoid weight gain, the provider must assess the patient’s body image issues and work with her/them to develop a regimen that will best serve her/them.

Insights from Studies about Body Image and Communication

Researchers have offered insights that both comport with, and differ from, the advice and preferences of our patient-partners. Helms et al., for example, found that providers believe body image concerns should be discussed as a routine part of clinical care. These conversations can be a part of the annual screening, with more frequent follow-ups as needed [3]. The researchers stress that it is important for the patient to feel comfortable enough to have these conversations.

Although the study looked at young adults, some of its findings can also be applied to older adults. Helms acknowledges that a strong interpersonal connection between the patient and provider is needed in order to have conversations about body image. The timing and circumstances of these conversations is also important to make the patient feel comfortable enough to disclose their concerns and issues [3]. Unlike CFReSHC patient-partners, who believe body image exceeds the scope of weight and growth, these researchers found that participants preferred that providers broach conversations about body image within the context of health-related topics, such as weight, growth, and nutrition since they saw a close link between nutritional status and its effect on overall health and lung function [3]. Like our patient-partners, Helms found most providers are unsure how best to bring up this topic with their patients; they feel they do not have adequate knowledge or familiarity with body image concerns. This knowledge gap can be a significant barrier to providing more routine, in-depth discussions, and can affect providers’ personal comfort level with raising the topic [3].

Other researchers provide additional insights about conversations and knowledge gaps about body image in people with chronic illness. Quick et al. recommend that healthcare professionals attain training in methods to increase patient empowerment with regard to body image issues. Empowerment may, in turn, have positive effects on attitudes toward those with chronic health conditions as it provides these patients with social-environmental support [2]. Watson et al.’s work on diet and exercise in Cystic Fibrosis recommends providers consider taking a nutritional management approach that takes into account patients’ attitudes toward eating, shape, and personal appearance. Utilizing this approach involves a paradigm shift, especially after the emergence of CFTR modulators. With this type of approach, they can emphasize healthy eating rather than a high calorie and fat diet [16]. Watson also suggests one way of improving body image among young people with CF is to teach them that being attractive does not depend on their physical appearance [16]. Other ways to improve patients’ physical self-image can include addressing and challenging media messages head-on that endanger a patient’s body image on a regular basis [16].

Managing Body Image Disturbance

Many disease processes, medical and surgical interventions, and specific patient factors contribute to changes in body image. Providers who can assess and manage their patients’ body image issues can help facilitate positive patient experiences and outcomes [3]. Though there are surgical interventions that can address some body issues, these do not work if a woman believes that she is disfigured, yet, does not actually have an impairment. In the latter cases, providers can suggest ways to reframe her experience, like meeting someone with a similar problem and learning about her coping strategies [3]. Providers can also manage patients’ body image via pharmacologic interventions for anxiety or depression, or they can use behavioral modification to teach coping skills and relaxation techniques. They can also suggest lifting weights to build muscle. In short, patients and their providers may need to collaboratively problem-solve on many levels – psychological, emotional, medical, physical, spiritual, and cultural – to assist with managing body image issues [3].

The Impact of Body Image Concerns on Women’s Lives: Patients’ Perspectives

Our patient-partners acknowledge that poor body image can lead to feelings of low self-esteem. They state they are embarrassed or feel ashamed from PICC lines, ports, feeding tubes, and transplant scars. These markings and devices can negatively affect their relationships and intimacy. Many women with CF also feel self-conscious over how others view them and what others may say because of the physical manifestations of CF. Women are bothered, for example, that other people may notice when they cough, when people comment about being too thin, about having clubbed fingers, about taking enzymes when eating, or about gaining weight of more than 20+ pounds.

Significant weight gain since starting CFTR modulators has also impacted women’s self-esteem and feelings of attractiveness. Their clothes don’t fit. They don’t recognize the bodies they are now inhabiting. Yet, while many women have negative body image concerns, some women with CF view their issues as sources of strength and survival.

There is a dearth of research about how people of color experience CF or how it impacts their body image. It is unclear, for instance, how scar tissue from surgeries or from IV lines impact CF patients of color’s body image. Struggles around weight are also not well-studied. One recent study by Ladores and her team, however, documents some experiences of African American patients with CF. The publication reflecting the findings of this study quotes a Black female patient who relayed that a nurse used stereotypical imagery in her interaction with the patient: “She [the nurse] was like, ‘I thought you had a Black girl booty. I got more butt than you do.’…I don’t want to be rude or disrespectful, but at the same time, that doesn’t give you the room to say little side stuff that doesn’t have to do with my health…because how do you know I’m not already insecure about stuff like that, which I was. The little progress that I did make, now we’re back to square one.”[7] Quotes like this one shows that there is still much work (including medical education interventions, research, and quality improvement) that needs to be done to understand and address the various body image concerns and encounters of patients of color in the CF community.

Peer to Peer Advice

- If you feel that you have postural changes (shoulders look slumped), ask your CF care provider if you can work with a physical therapist. A physical therapist can provide you with stretches/exercises to help with this. Sometimes wearing baggy clothing can help hide the changes as well.

- Try focusing on what your body does for you, rather than perceived negative aspects (i.e. I have two legs that allow me to walk, run. I have two eyes that allow me to see my family, friends, colors, etc.)

- Recognize you are not alone. Many others feel the same way you do about their bodies. There are people who have the same scars, ports, feeding tubes, etc. that you can talk to.

- Honor your body and buy clothes that fit you. Your clothes should fit you, not the other way around!

- See your scars as a reminder that you are a survivor! Scars are nothing to be ashamed of.

- Discuss the importance of minimizing body talk with your friends and loved ones. Ask them to avoid saying things like: “You look great! You’re so skinny!” and “You’re so lucky you can eat whatever you want and look like that.” Instead, focus on praising individuals on their hobbies and personality traits, such as: “You are such a wonderful listener.” or “I love how passionate you are about ___.”

- Remember that true beauty is not simply skin-deep.

- Consciously seek out media that reinforces positive self-image.

- Repeat after me, “My weight does not define my worth!”

- When your doctor clears you after a lung transplant, lung rehabilitation is an excellent way to get exercise and maintain a healthy weight. In addition, getting involved in volunteer activities, hobbies, and family activities help to move your focus away from negative changes.

- If a provider talks negatively about your body, find a new provider that will support you.

Resource Links

- Beam Feel Good: Movement to make you feel good. Access on-demand and live exercise classes, led by specialist physiotherapists and trainers who are trained in, or live with your health condition.

- Pulmonary Performance Institute: Online physical training for patients with CF

- Salty Girls Project

- International Transplant Nurses Society (ITNS). Lung Transplant Patient Education Booklet-A Guide to your Health Care after Lung Transplantation. September 19, 2019.

- Purchase wireless bras: Lively.com, Thirdlove.com, Aerie

- The Body Positive Website

- Body-Positive Resources

- Anti-Diet/Body Positive Instagram Accounts:

- @kristamurias

- @jennifer_rollin

- @rebeccascritchfield

- @antidietlife

- @bodyimagewithbri

- @healing crayons

- @kristenmurrayrd

- @evelyntribole

- @ownitbabe

- @endangered.bodies

Works Cited

- Barrett J, Slatter G, Whitehouse JL, Nash EF. Perception, experience and relationship with food and eating in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2022;35(5):757-764. doi:10.1111/jhn.12967

- Mailhot G, Denis MH, Beauchamp-Parent C, Jomphe V. Nutritional management of people living with cystic fibrosis throughout life and disease continuum: Changing times, new challenges. J Hum Nutr Diet Off J Br Diet Assoc. 2023;36(5):1675-1691. doi:10.1111/jhn.13214

- Darukhanavala A, Merjaneh L, Mason K, Le T. Eating disorders and body image in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2021;26:100280. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100280

- Petropoulou A, Bakounaki G, Grammatikopoulou MG, Bogdanos DP, Goulis DG, Vassilakou T. Eating Disorders and Disordered Eating Behaviors in Cystic Fibrosis: A Neglected Issue. Child Basel Switz. 2022;9(6):915. doi:10.3390/children9060915

- Kass AP, Kazmerski TM, Bern E, et al. Clinician perspectives on assessing for disordered eating and body image disturbance in adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2023;22(3):431-435. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2022.11.006

- Didsbury J, Thackray E. Body Image and Cystic Fibrosis. Cyst Fibros Trust. Published online November 13, 2010.

- Ladores S, Woods BM, Pitts LN, Belay D, Washington L, Bray LA. The Lived Experience of African American Persons with Cystic Fibrosis. Creat Nurs. 2023;29(4):374-382. doi:10.1177/10784535231216461

- Abbott J, Morton AM, Musson H, et al. Nutritional status, perceived body image and eating behaviours in adults with cystic fibrosis. Clinical Nutrition. 2006;26(1):91-99. https://www.clinicalkey.es/playcontent/1-s2.0-S0261561406001476. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.08.002.

- Quick VM, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Neumark-Sztainer D. Chronic illness and disordered eating: A discussion of the literature. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.). 2013;4(3):277-286. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23674793. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003608.

- Helms SW, Christon LM, Dellon EP, Prinstein MJ. Patient and provider perspectives on communication about body image with adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2017;42(9):1040-1050. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28369522. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsx055.

- CF Reproductive and Sexual Health Collaborative. CFReSHC Patient Task Force meeting on Body Image. 3.13.2020.

- Sheikh S, Zemel BS, Stallings VA, Rubenstein RC, Kelly A. Body composition and pulmonary function in cystic fibrosis. Frontiers in pediatrics. 2014;2:33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24783186. doi: 10.3389/fped.2014.00033.

- Whiteman MK, Oduyebo T, Zapata LB, Walker S, Curtis KM. Contraceptive safety among women with cystic fibrosis: A systematic review. Contraception. 2016;94(6):621-629. https://www.clinicalkey.es/playcontent/1-s2.0-S0010782416301159. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.05.016.

- Litvin M, Yoon JC, Leey Casella J, Blackman SM, Brennan AL. Energy balance and obesity in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Journal of cystic fibrosis. 2019;18:S38-S47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.015. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.015.

- Harindhanavudhi T, Wang Q, Dunitz J, Moran A, Moheet A. Prevalence and factors associated with overweight and obesity in adults with cystic fibrosis: A single-center analysis. Journal of cystic fibrosis. 2020;19(1):139-145. https://search.datacite.org/works/10.1016/j.jcf.2019.10.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2019.10.004.

- Bolton MA, Lobben I, Stern TA. The impact of body image on patient care. Primary care companion to the Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2010;12(2). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20694111. doi: 10.4088/PCC.10r00947blu.

- Michigan Medicine University of Michigan. Emotional recovery after lung transplant. http://www.med.umich.edu/pdf/lung-transplant/EmotionalRecovery. Updated 2018. Accessed 2.22.2020.

- Hanna RM, Weiner DJ. Overweight and obesity in patients with cystic fibrosis: A center‐based analysis. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2015;50(1):35-41. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ppul.23033. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23033.

- Cystic Fibrosis Trust. A transplant booklet for people with CF. https://www.cysticfibrosis.org.uk/what-is-cystic-fibrosis/cystic-fibrosis-care/transplant-information-and-resources#Transplant%20booklets. Updated 2018. Accessed 2.20.2020.

- Davies JC, Li H, Yen K, Ahrens R. WS6.5 ivacaftor in subjects 6 to 11 years of age with cystic fibrosis and the G551D-CFTR mutation. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2012;11:S13. https://www.clinicalkey.es/playcontent/1-s2.0-S1569199312600435. doi: 10.1016/S1569-1993(12)60043-5.

- Borowitz D, Lubarsky B, Wilschanski M, et al. Nutritional status improved in cystic fibrosis patients with the G551D mutation after treatment with ivacaftor. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;61(1):198-207. https://search.datacite.org/works/10.1007/s10620-015-3834-2. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3834-2.

- Stallings VA, Sainath N, Oberle M, Bertolaso C, Schall JI. Energy balance and mechanisms of weight gain with ivacaftor treatment of cystic fibrosis gating mutations. The Journal of pediatrics. 2018;201:229-237.e4. https://search.datacite.org/works/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.018. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.018.

- Watson R. Diet and exercise in cystic fibrosis. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9780128000519. Updated 2015.

- CF Reproductive and Sexual Health Collaborative. CFReSHC Snap Poll on Body Image. 2.23.2020.

Free Printable PDF Download

Want a free printable PDF download of this section for your use in clinic? Just give us your name and email address below to get your download link. This will not add you to our email list.