Nutrition, Weight, and CFTR Modulators

A New Landscape for People with CFCFReSHC CF-SRH Resource Guide by Patients for Providers and Patients

Key

For Providers

For Patients

For Patients and Providers

Introduction

Highly effective modulator therapy (HEMT) was added to the cystic fibrosis (CF) treatment plan in recent years. This includes elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor (ETI), or by more common names: Kalydeco™, Orkambi™, Symdeco™, and Trikafta™. Research data is showing that weight gain and obesity rates in the CF population is increasing. (link to Julianna’s presentation data) Dr. Gregory Ratti, assistant professor at University of Texas Southwestern warns that excessive weight gain issues “will likely become more apparent, and therefore poor health conditions associated with that may also arise.” a. He asserts that we need to recognize these early to prevent long-term problems as life expectancy improves for our patients.” In 1999, 12.8% of CF patients were overweight or obese. In 2019 the CF Foundation reported about 23.1% of the CF population was overweight, and another 8.3% were obese. After starting Trikafta™, BMI increased. As weight gain, obesity in CF increases, the impact on a patient’s health and long-term health issues require further study.

In this chapter, we will take a look at how the reported weight gain is impacting nutrition and food intake. Until recently, CF nutrition guidelines recommended an unrestricted high-calorie high-fat diet, with little focus on nutrients or diet quality. As clinical care and treatments for CF have improved over the past decade, the standard recommended CF diet may have once led to positive energy balance and excessive weight gain in some people with CF (PwCF) but is now contributing to other serious health conditions with the introduction of HEMT. Extended life expectancy is starting to focus on diet quality to promote optimal health outcomes and prevention of other chronic lifestyle diseases in CF (Bailey, J 2022).

- What are some concerns or questions you might have regarding highly effective modulator therapy and the foods you eat?

- We have noticed some patients do gain weight on highly effective modulator therapy. Is this a concern for you?

- Trikafta™, Orkambi™, Kalydeco™, and/or Symdeco™ is taken with a fatty meal to help with absorption. Is this going to be a problem?

- Can I take my modulator when I eat breakfast and dinner?

- How much fat do I need for absorption?

- Is there anything I should be concerned about based on my age?

- Is being hungry have anything to do with your vitamin or mineral levels and not necessarily modulators?

- If I start gaining too much weight, can I adjust the dosage?

Research

Patients with Cystic Fibrosis are often advised to consume more calories than their health peers. . This is because they need to “offset the negative energy expenditure created by malabsorption, increased work of breathing, inflammation, and pulmonary exacerbations” [3]. Despite the knowledge surrounding CF, nutritional guidelines seem to vary, and scientific advances are evolving quickly, leaving scientists questioning the traditional guidelines [13].

Birgitta Strandvik, raised the point that previous research typically recommended a high energy diet with higher fat and protein intake, but specific needs were rarely pinpointed (source). However, not all fats are created equal, and the quality of fat intake required in this diet demands scrutiny in lieu of current weight gain issues experienced by some CF patients on HEMT.

The type of fat that is consumed by the individual is reflected in the cell membranes that influence transport and metabolism. Many researchers are now advocating that fat intake guidelines should be personalized given each individuals’ particular needs. Despite this emphasis on high energy intake with special attention given to fat and protein intake, the recommendations are rarely achieved [5].

Despite the classic rhetoric of a high energy diet, and the typical inability to reach certain goals and metrics, the prevalence of obesity in patients with CF is increasing[1]. It is important to note that this uptick in obesity cannot purely be attributed to the nutritional guidelines, as “the causes of excess weight gain in CF are likely multifactorial, including: adherence to the high-fat legacy diet, reduced exercise tolerance, therapeutic advances, and general population trends” [2]. A downfall with the high-fat recommendation, is that many fats that are consumed are of poor quality. Additionally, after individuals have been instructed to consume a high energy diet, it is difficult to transition to a diet with a lower calorie recommendation. Weight loss therapies for patients with CF are also harder to manage due to the “need to balance the risk of declining BMI on lung function with the possible metabolic advantages of lower BMI” [2]. Overall, this increase in obesity within the population of individuals living with CF is simply mirroring the epidemic of obesity in the general population.

Advances in science are contributing to the “increased lifespan and decreased symptoms in many individuals with CF, necessitating a reexamination of the high-fat CF legacy diet” [4]. In a literature search, Medline, Embase, and CINAHL databases were combed through to identify articles published between the years 2002 and 2018 that focused on the relationship between macronutrient distribution and nutrition outcomes in patients with CF. The results of this search yielded no information about the outcome of mortality or the quality of life. The review demonstrated that there is a wide range in the dietary macronutrient intake of patients with CF, but there is little to no demonstrable relationship between the macronutrient distribution and nutrition related outcomes.

One of the many scientific advances which have led to an increase in lung function and weight is the treatment of ivacaftor or Kalydeco™ for patients with CF who carry the G551D mutation. However, the short and long term effects on body composition have not been well studied. In a double-blind, placebo controlled, randomized, crossover study with open label extension, researchers found that after 28 days of treatment with ivacaftor, weight increased by 1.1 ± 1.3 kg, BMI by 0.4 ± 0.5 kg/m2, and FFM by 1.1 ± 1.2 kg (all P < .005) with no change in fat mass [1]. The differences between the 28 day changes on ivacaftor vs the changes on the placebo were not statistically significant. In conclusion, there were small gains in the first 28 days on ivacaftor, but changes plateaued by 2.5 years. Researchers have yet to determine the metabolic and clinical consequences of weight and fat-mass gains in patients with CF.

In a 2021 study held at the Washington University Adult Cystic Fibrosis Center, researchers performed a single-center, retrospective, observational analysis of the effect of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor or Trikafta™ on body weight and cardiometabolic parameters in 134 adult CF patients. Body weight, BMI, and blood pressure were extracted from outpatient clinic visits for the year preceding and the period following the initiation of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor or Trikafta™ . Other metabolic parameters were extracted at baseline and at latest available follow-up [6]. This study showed initiation of elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor or Trikafta™ was associated with increases in BMI at a mean follow up of 12.2 months. Changes in other cardiometabolic risk factors were also observed. Widespread use of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor or or Trikafta™ may be expected to increase the incidence of overnutrition in the CF population [6]. To support this finding, Dr. Julianna Bailey et al. reported a decrease in resting energy expenditure, improved intestinal absorption, and increased caloric intake were shown for patients taking Trikafta, however, more studies of longer duration are needed to examine body composition and fat distribution changes on CFTR modulators in the setting of unintended weight gain and the development of overweight and obesity on these drugs [7].

In general, the relationship between nutrition and Cystic Fibrosis needs to be further explored. The constantly evolving landscape of treatment for CF patients is making it difficult for doctors and researchers to deeply understand the exact recommendations that should be made to patients.

Modulators

In 1989, researchers discovered the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) protein. CFTR regulates the proper flow of water and chloride in and out of cells lining the lungs and other organs.[2] Mutations in the CFTR gene result in either a defective protein or no protein at all being produced, and this defect can lead to multiorgan health concerns.[2]

In recent years, CF clinic teams added highly effective modulator therapy (HEMT) to the cystic fibrosis (CF) treatment plan to help regulate the proper flow of water and chloride in and out of cells lining the lungs and other organs. CFTR modulators include –elexacaftor, tezacaftor, and ivacaftor (ETI)– known as TrikaftaTM. Other modulators include Kalydeco™ (ivacaftor), Orkambi™ (lumacaftor and ivacaftor), and Symdeco™ (tezacaftor and ivacaftor). Despite side effects, modulators have significantly improved individuals’ pulmonary health and quality of life.[3]

Nutrition

Because of pancreatic insufficiency, many CF patients experienced malnutrition in the past. Treatment plans often included the “Legacy CF Diet” (a high-fat, high-calorie diet) because weight gain was associated with better health outcomes.4 Researchers and clinicians theorized that the Legacy CF Diet would “offset the negative energy expenditure created by malabsorption, increased work of breathing, inflammation, pancreatic insufficiency, and pulmonary exacerbations.”5 Because past studies typically recommended a high-energy diet with higher fat and protein intake, clinical management did not adequately focus on patients’ food choices, dietary needs, and eating habits.6 As Dr. A. Uluer has stated, the “historical CF diet previously focused on nutrition-poor foods, saturated fats, and excessive sugar.”7

A changing dynamic around nutrition in the age of HEMT necessitates that researchers and clinicians reconsider past nutritional guidelines. Even before HEMT, Jimenez et al. argued that an “increased lifespan and decreased symptoms” amongst patients with CF demands that providers reconsider the historical CF diet.8 Since poor childhood eating habits can impact adult eating behaviors, “it is likely that people with CF will have difficulty transitioning to a lower-calorie diet after a lifetime of consuming high-calorie, high-fat foods.”3 Nutritional needs should be assessed on an individual basis, factoring in which and what dose modulator the individual is taking, their current health status, and their socio-economic background. The Academy for Nutrition and Dietetics: 2020 Cystic Fibrosis Evidence Analysis Center Evidence-based Nutrition Practice Guideline considers the use of ETI on patients’ weight and provides detailed provisions for providers to follow in both CF pediatric and adult nutrition care.9

Weight

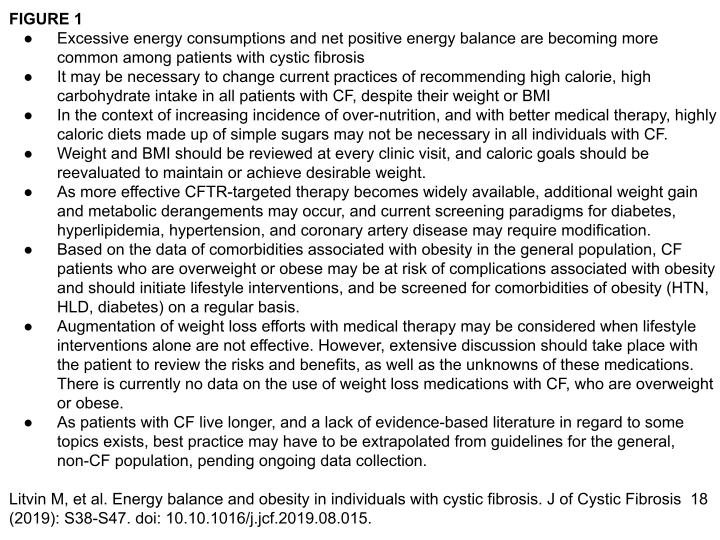

Data has shown that the number of patients with CF who are obese or overweight has doubled in the past 20 years.10 In the age of HEMT, this trend has become exacerbated.4 Leonard et al. hypothesize that “HEMT likely contributes to an increase in weight by reducing energy expenditure for breathing, improving smell/taste, enhancing appetite, optimizing fat absorption/intestinal pH increasing fat mass and presenting the need to take the medication with fatty foods.”1 The CF Foundation has not formally updated the CF Nutrition Guidelines since obesity and overweight have emerged as significant issues or since highly effective CFTR modulators recently became available for about 90% of the CF population.4 However, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics has.9 Litvin et al., in their article, “Energy balance and obesity in individuals with cystic fibrosis” (2019), have also provided excellent clinical practice points for CF teams to take into consideration, featured in Figure 1.11

Researchers must continue to understand the impact of weight gain and obesity on patients’ short and long-term health. Being overweight or obese in the general population can cause health complications like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, sleep apnea, and other comorbidities. Clinic teams are now focusing on diet quality as a way to promote optimal health outcomes and prevent other chronic lifestyle diseases in CF.9,12

Understanding Diet Recommendations

The evolving landscape of treatment for CF patients has made it difficult for doctors and researchers to recommend an appropriate diet for patients with CF. Nutrition for patients with CF has long been a focal point in clinical management. Because the CF Foundation Patient Registry data (CFFPR) showed a strong positive correlation between nutritional measures (e.g., BMI) and lung function, the CF Foundation set BMI goals above the 50th percentile for children and ≥22 kg/m2 for adult females and ≥23 kg/m2 for adult males with CF.13 Because of the history of malnutrition in the CF population and its effects on lung function, most nutritional interventions focused on increasing BMI. CF Centers often prioritized nutrition and weight gain, even as they saw patients exceeding the 50th percentile in BMI.3 Yet a recent 2021 article by Kutney et al. cites studies that people with a BMI above 25 kg/m² do not generally show improvements in FEV₁.13

Further, recent discussions in the CF world are re-examining the wisdom of using BMI as the proper measure for patients with CF. BMI, for instance, does not account for bone mass, muscle, fat, or a genetic predisposition to the normal metabolic process in the body. Neither does it encompass various cultural eating habits. As such, there are increasing calls to replace BMI with other measures.14 Until evidence-based guidance on dietary recommendations for CF patients is available, clinic teams need to personalize nutritional recommendations using an individual’s clinical data and the patient’s weight goals.1

While significant changes in weight and BMI have been seen with ETI, it is vital to investigate the height, weight, and body mass index in people with CF (PwCF) on HEMT. HEMT likely contributes to an increase in weight by reducing the energy expenditure for breathing. It improves smell/taste, enhances appetite, and optimizes fat absorption/intestinal pH.15,16 Weight gain also results from the need to take modulators with food that has fat.1 There is an ongoing study [STRONG study, NCT05639556; Strength and Muscle Related Outcomes for Nutrition and Lung Function in CF; ] that seeks to compare markers of body composition with sarcopenia (loss of bone mass) using DXA scans. The study will look at nutritional and body composition measures and link them to the clinical outcomes of patients with various pulmonary function.17 Long-term studies like this one will increase knowledge about the effect of HEMT on patients’ nutritional status. It will also answer questions about whether weight gain from HEMT eventually plateaus–signaling a metabolic equilibrium– or if weight gain continues to rise, which would pose a risk for obesity.16

Scientific knowledge about nutrition and CF is rapidly changing, particularly since weight gain and obesity are becoming a significant issue.18 This is due, in part, to a rise in obesity in patients with CF, which mirrors the obesity epidemic in the US.18 According to Petersen et al., “the causes of excess weight gain in CF are multifactorial, including: adherence to the high-fat legacy diet, reduced exercise tolerance, therapeutic advances, and general population trends.”19 Individuals are now instructed to follow a high-energy, low-calorie diet but are having difficulty transitioning to it.

As of 2023, researchers are starting to study the effects of ivacaftor on weight gain. For instance, in 2021, King explored the relationship between lung function and weight among patients with the G551D mutation treated with ivacaftor.20 Patients gained significant weight in the first month and an additional five months of treatment. Mean weight increases were primarily composed of fat mass, with only small gains in fat-free mass in the first month of ivacaftor and after six months. Minimal body composition changes occurred once patients were stabilized on ivacaftor; weight, fat mass, and fat-free mass plateaued by two years.20 Petersen’s retrospective study, conducted in 2021 at the Washington University Adult Cystic Fibrosis Center, examined the effect of ETI on body weight and cardiometabolic parameters (n=134).19 The study looked at outpatient records, focusing on body weight, BMI, and blood pressure measures from the preceding year and the year following the initiation of ETI. The researchers measured other metabolic parameters, cardiometabolic risk factors at baseline, and each participant’s most recent follow-up.19 Results showed an association between ETI use and BMI increases. Significant increases in blood pressure and hyperlipidemia also occurred. The researchers concluded that widespread use of ETI may increase the incidence of overnutrition in the CF population.19 Leonard et al. have confirmed this finding of hypertension among PwCF, stating that “7.2% of adult pwCF had a diagnosis of hypertension” in 2021.1 They also showed a growing incidence of hypertension and metabolic syndrome in CF patients on ETI.1,19,21 Bailey, Litvin, and Yoon reported additional outcomes. They found patients experience a decrease in resting energy expenditure, an improvement in intestinal absorption, and an increase in caloric intake.4,11,18 To be sure, more extensive studies are needed to examine the relationship between body composition and fat distribution changes on CFTR modulators, unintended weight gain, and rates and mechanisms of becoming overweight and obese on these drugs.4

Treatment Options

Changing their eating habits is problematic for patients used to the Legacy diet. The Endocrine Society recommends pharmacologic therapy for adults with a BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 who have co-morbidities and a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 for those without co-morbidities.3 Providers must balance a patient’s weight reduction needs and the metabolic benefits of a lower BMI with the risk of a lower BMI on lung function.3

Changing their eating habits is problematic for patients used to the Legacy diet. The Endocrine Society recommends pharmacologic therapy for adults with a BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 who have co-morbidities and a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 for those without co-morbidities.3 Providers must balance a patient’s weight reduction needs and the metabolic benefits of a lower BMI with the risk of a lower BMI on lung function.3

Changing one’s diet is typically the first approach recommended for treating obesity. Reducing calories by 500–1000 kcal/day can usually produce a healthy weight loss of 1-2 lbs per week.3 Calorie reduction requires adding a food diary or a mobile phone app to track food choices and caloric intake to patients’ treatment regimens. Such tracking may be a struggle for people with CF due to a lack of time, daily treatment regimens, and other activities.

With weight gain from HEMT, PwCF may experience weight stigma. Care teams need to acknowledge the mental impacts of undesired weight gain on patients’ body image and consider using WNAs (weight-neutral approaches) to lifestyle interventions.1 The latter should include discussing diet with the care team, modifying behavior (e.g., adding regular exercise to address a sedentary lifestyle), and nutritional education or re-education.

Some patients may prefer to reflect on other health markers rather than BMI or weight, like lower blood pressure or cholesterol or less pain when considering their motivations for weight loss. Bailey and colleagues cite the HAES (Health at Every Size) approach as optimal, especially for patients with a history of disordered eating or body image issues: Instead of promoting weight loss, the Health at Every Size (HAES®) approach focuses on improving physical, behavioral, and psychological profiles.4 This weight-inclusive model emphasizes accepting one’s body and optimizing one’s relationship with food (see the Body Image chapter for body image and eating disorders). Though HAES is a weight-neutral program, it can improve quality of life, heart health, heightened physical activity, improved diet quality, lower BMI and waist circumference, and facilitate fat loss.4

Healthy Eating

To help with the nutrition and weight issues associated with HEMT, different styles of healthy eating are important to learn. Below are types of diets from around the world that center on nutrient dense and high quality foods. The people who eat these diets have shown to live longer healthier lives.

- Mediterranean Diet – Whole grains, legumes, fresh fruits, and fresh vegetables are produced locally. Fish and poultry are consumed in moderation (2-3 times/week), but meat, sugar, and salt are saved for special occasions.

- Traditional Okinawa Diet – This eating plan is a low-calorie, nutrient-dense diet. It focuses on fresh fruits and fresh vegetables with modest amounts of seafood and lean meat. The idea is to eat enough food to feel 80% full.

- Nordic Diet – Rich in root vegetables, whole-grain bread, and oily fish, the Nordic diet is high in fiber and protein, but low in sugar. Meat dishes and processed dairy products are limited, but fermented milk and cheese are common ingredients.

- West African – Centered on lean meat, vegetables, and cereal staples, the West African diet is low in calories and nearly devoid of processed foods. This diet focuses on traditional preparations of foods like fresh fruit, fresh vegetables, whole grains, and fish.

It’s important to compare these styles of eating to how we traditionally eat in the US. The Western Diet, as it is referred to, is known for being rich in saturated fats, refined carbohydrates and fats. This type of diet is known to cause highly addictive-like eating behaviors, including overeating fats and sugars, causing long term changes in the brain. By eating nutrient rich, fresh foods you can retrain your brain and the foods it craves. Here are some helpful tips to focus on:

- Focus on plant-based foods such as legumes, beans, fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and healthy fats. Enjoy fresh, in-season produce and fish and use lean meat as sparingly as possible.

- Make breakfast your largest meal of the day and eat smaller meals in the afternoon and evening. Limit your portion sizes and stop eating when your stomach feels about 80% full.

- Consume as little added sugar as possible. Get most of your daily intake from natural sugars found in fruits and vegetables. Save sweets for occasional treats.

- Choose whole, natural foods that have not been processed or altered. Eat as much locally produced, in-season food as you possibly can. And use cooking methods that preserve the nutritional integrity of the raw ingredients.

- Drink plenty of water and reduce or stop drinking soft drinks and/or sugary drinks like some fruit juices.

- Eat processed foods (cereals, crackers, chips, granola bars, etc.) in moderation.

- Try to avoid canned fruits and vegetables. If you can’t find fresh, then frozen is the next best choice.

- Green tea and black coffee are ok to drink. Avoid fruit juices that have added sugar.

- Be careful with dairy products as they can be high in fat and calories, such as cheese. When eating dairy stick to greek yogurts and low fat or plant-based milks.

I stopped snacking late at night, watched my sugar intake and cut back on wine to control my weight.

I was hungry and gained 20 Ibs on trikafta in 1.5 yrs; maybe menopause and lack of movement with Covid but I had to get a new wardrobe. I stopped snacking at night, cut ice cream, popcorn, given up a little up a bit of wine.

Food Insecurity and Socio-Economic Factors

Demanding CF medical regimens commonly limit income-earning ability for parents or adult patients, which creates financial stress. On its website the CFF asserts that 71% of people with CF have experienced some form of financial hardship due to medical bills. In 2019, the CFF asked researchers from the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University to conduct the 2019 CF Health Insurance Survey. The online survey offered nine questions on social determinants of health. The survey indicated that 38% of non-elderly adults with CF in the U.S. were on disability. Eight out of ten respondents indicated that their financial burdens negatively impacted their quality of life. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), food-insecure households are those with “limited or uncertain access to adequate food” and in 2019, 10.5% of US households faced food insecurity. Food insecurity in the CF community is three times the national average and over one-quarter participate in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly food stamps). Limited income produces two problems for those in the CF community: limited funding for both housing and food.

For those with less funding for food, and/or those participating in SNAP, healthy food choices become an obstacle. Researchers realize the food prices dictate purchase decisions because boxed meals are often cheaper than fresh fruits, vegetables, and protein sources. (source) Additional, lower incomes often push members of the CF community to housing areas that experience a food desert or an area where it is difficult to find and purchase affordable good-quality fresh food because there are no markets or big box stores with healthy food options. .. These factors also impact diets of members of the CF community. There are many sites that offer discounted foods delivered to your home, and many of these sites accept a flexible spending account card, a health savings account card, and supplemental nutrition assistance program electronic benefit transfer card. Here is a list of sites to compare:

Local food banks can offer fresh fruits, vegetables, and meats to those facing financial hardships.

Thrive Market: https://thrivemarket.com

Imperfect Foods: www.imperfectfoods.com

Boxed: www.boxed.com

Amazon Fresh if you are a prime member: www.amazon.com

Walmart Grocery: www.walmart.com

Misfits Market: https://www.misfitsmarket.com

The Hungry Root: www.hungryroot.com

Conclusion

Since the introduction of HEMT, there has been a significant increase in the life expectancy of PwCF. Addressing lifestyle changes, such as eating habits and exercise, has become a key component of CF care to combat the incidence of weight gain and address the comorbidities that come with living longer.

According to the 2022 CF Patient Registry, 82% of PwCF use HEMT, and 40.9% of all PwCF are within the BMI ranges that the CDC characterizes as overweight or obese.25 While some of the prevalence of obesity can be attributed to factors beyond HEMT (e.g., personal eating habits, financial stressors, and national trends), CF clinic teams should emphasize preventing weight-related comorbidities in their nutritional counseling and individualized dietary recommendations.

Patients can also modify their diet by controlling portion sizes and eating fresh foods as much as possible. They can also increase their exercise if they have gained weight on ETIs. While these changes might be challenging, taking steps to better manage weight gain is important to stave off diseases associated with being overweight or obese, like cardiovascular disease, high cholesterol, diabetes, and fatigue, among others.

Leonard et al. developed an assessment tool that can help CF clinic providers. “An Interprofessional Team’s role in weight management and food insecurity assessment” addresses the potential roles of the patient and provider.

An Interprofessional Team’s role in weight management and food insecurity assessment

| Team Member | Role in Weight Management and Food Insecurity Assessment |

| Patient and Family |

1. Provide input on food preferences, cultural practices, and nutrient-dense food access 2. Participate in shared decision-making |

| Dietitian |

1. Perform diet recalls identifying opportunities for optimizing dietary intake 2. Recommend strategies to enhance diet quality 3. Review labs and provide recommendations on micronutrients (both deficiency and excess) 4. Evaluate for manifestations of malabsorption and adjustment of pancreatic enzyme dosage 5. Body composition measurements may be performed in the clinic (bioelectrical impedance analysis), and alternative measures of nutritional assessment (skin fold thickness, hand-grip strength, etc.) 6. Provide education for PwCF and family 7. Provide supportive counseling around body image and weight stigma 8. Screen for food insecurity |

| Social Worker/Clinical Psychologist/Mental Health Coordinator |

1. Provide psychosocial support around body image and weight stigma and implement behavioral change strategies 2. Screen for depression, anxiety, disordered eating, and food insecurity 3. Provide resources and interventions for patients with positive screening 4. Follow up after the clinical visit to ensure resources provided were helpful |

| Pulmonologist/ Physician/Advanced Practice Providers (primary care physician may play a shared role for certain conditions) |

1. Evaluate/provide a referral for CF-related comorbidities, which may increase with obesity (eg, CFRD) 2. Evaluate/provide referral for obesity-related comorbidities such as obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease 3. Reinforce the importance of a healthy diet and exercise with PwCF, and assess adequate nutrient-rich foods. |

| Gastroenterologist |

1. Evaluate and manage gastrointestinal comorbidities of obesity (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux disease, cholelithiasis, hepatic steatosis) 2. Evaluate and manage CF-related or obesity-related liver disease 3. Evaluate pancreatic function and manage pancreatic insufficiency 4. Manage gastrointestinal/hepatic manifestations of ETI |

| Nurse Coordinator/Research Nurse | 1. Encourage communication between the PwCF and the team and facilitate coordination between team members in issues related to weight management. |

| Endocrinologist/Obesity Specialist |

1. Evaluate and manage dyslipidemia 2. Evaluate the need for medical/surgical management for obesity 3. Discuss the effect of medical/surgical management of obesity on CF-related diabetes and malabsorption |

| Physical Therapist/Physiotherapist |

1. Measure functional ability: stamina, endurance, and ADLs (activities of daily living) 2. Provide customized exercise programs to integrate physical activities into a healthy lifestyle and optimize lean body mass. |

| Pharmacist | 1. Assess drug-nutrient and drug-drug interactions, including weight loss drugs |

Leonard A, Bailey J, Bruce A, et al. Nutritional considerations for a new era: A CF foundation position paper. J Cyst Fibros. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2023.05.010

Photos courtesy of: https://www.istockphoto.com

Peer to Peer Advice

- Don’t stress over taking your modulators with enough fat, certain types of fats or certain foods. Take them with a meal when you eat.

- Don’t stress over the time intervals with meds.

- Drink a glass of water before you eat. This can help fill you up so you won’t overeat.

- Try to exercise at least 60 minutes a day 3-5 days per week.

- Get at least 8 hours of sleep. Lack of sleep is directly linked to feeling hungrier and overeating. People who are sleep deprived also tend to eat higher calorie foods to feel fuller.

Works Cited

- Leonard A, Bailey J, Bruce A, et al. Nutritional considerations for a new era: A CF foundation position paper. J Cyst Fibros. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2023.05.010

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Managing CF/Medications/CFTR modulator therapies. Accessed June 27, 2023. https://www.cff.org/managing-cf/cftr-modulator-therapies

- Kutney KA, Sandouk Z, Desimone M, Moheet A. Obesity in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2021;26:100276. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100276

- Bailey J, Krick S, Fontaine KR. The Changing Landscape of Nutrition in Cystic Fibrosis: The Emergence of Overweight and Obesity. Nutrients. 2022;14(6). doi:10.3390/nu14061216

- Guimbellot JS, Baines A, Paynter A, et al. Long-term clinical effectiveness of ivacaftor in people with the G551D CFTR mutation. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2021;20(2):213-219. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2020.11.008

- Donald C, DasGupta S, Metzl J, Eckstrand K. Queer Frontiers in Medicine: A Structural Competency Approach. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):345-350. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001533

- Uluer A. Aging with CF. Presented at: CFRI Annual Meeting; August 19, 2023.

- González Jiménez D, Muñoz-Codoceo R, Garriga-García M, et al. Excess weight in patients with cystic fibrosis: is it always beneficial? Nutr Hosp. 2017;34(3):578-583. doi:10.20960/nh.620

- McDonald CM, Alvarez JA, Bailey J, et al. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: 2020 Cystic Fibrosis Evidence Analysis Center Evidence-Based Nutrition Practice Guideline. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;121(8):1591-1636.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2020.03.015

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry Report 2021.; 2021. Accessed November 10, 2023.

https://www.cff.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/Patient-Registry-Annual-Data-Report.pdf

- Litvin M, Yoon JC, Casella JL, Blackman SM, Brennan AL. Energy balance and obesity in individuals with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:S38-S47. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.015

- CFReSHC Patient Meeting on Nutrition and Modulators.; 2022. youtube.com/watch?v=wYMdud-Va6Q&t=4s

- Szentpetery S, Fernandez GS, Schechter MS, Jain R, Flume PA, Fink AK. Obesity in Cystic fibrosis: prevalence, trends and associated factors data from the US Cystic Fibrosis Foundation patient registry. J Cyst Fibros. 2022;21(5):777-783. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2022.03.010

- Alvarez JA PhD,RD, Ziegler TR MD, Millson EC MS,RDN, Stecenko AA MD. Body composition and lung function in cystic fibrosis and their association with adiposity and normal-weight obesity. Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif. 2016;32(4):447-452. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2015.10.012

- Strandvik B. Nutrition in Cystic Fibrosis: Some Notes on the Fat Recommendations. Nutrients. 2022;14(4):853. doi:10.3390/nu14040853

- Frantzen T, Barsky S, LaVecchia G, Marowitz M, Wang J. Evolving Nutritional Needs in Cystic Fibrosis. Life Basel Switz. 2023;13(7):1431. doi:10.3390/life13071431

- Strength and Muscle Related Outcomes for Nutrition and Lung Function in CF. Observational Study.(2023). https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05639556

- Litvin M, Yoon JC. Nutritional excess in cystic fibrosis: the skinny on obesity. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2020;19(1):3-5. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.12.002

- Petersen MC, Begnel L, Wallendorf M, Litvin M. Effect of elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor on body weight and metabolic parameters in adults with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2022;21(2):265-271. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2021.11.012

- King SJ, Tierney AC, Edgeworth D, et al. Body composition and weight changes after ivacaftor treatment in adults with cystic fibrosis carrying the G551 D cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator mutation: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, crossover study with open-label extension. Nutr Burbank Los Angel Cty Calif. 2021;85:111124-111124. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2020.111124

- Despotes KA, Ceppe AS, Donaldson SH. Alterations in lipids after the initiation of highly effective modulators in people with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. Published online 2023. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2023.10.002

- Seyoum S, Regenstein M, Benoit M, et al. Cost burden among the CF population in the United States: A focus on debt, food insecurity, housing, and health services. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22(3):471-477. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2023.01.002

- Hunger and Food Insecurity. Accessed August 19, 2023. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/food-insecurity

- Sainath NN, Schall J, Bertolaso C, McAnlis C, Stallings VA. Italian and North American dietary intake after ivacaftor treatment for Cystic Fibrosis Gating Mutations. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18(1):135-143. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2018.06.004

25. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. CFF Patient Registry Annual Data Report 2022. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; 2022.

Free Printable PDF Download

Want a free printable PDF download of this section for your use in clinic? Just give us your name and email address below to open the PDF in a new tab.

This form will not add you to our email list.