Incontinence

The involuntary release of urine or fecesCFReSHC CF-SRH Resource Guide by Patients for Providers and Patients

Key

For Providers

For Patients

For Patients and Providers

Introduction

Studies indicate that patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) experience pelvic incontinence (PI) at higher rates than the general population [1]. There are five common forms of incontinence: stress, urge, overflow and fecal.

Stress

Occurs with sudden pressure on the bladder (coughing, laughing sneezing, exercising)

Urge

Occurs with strong sudden urge to void; overactive bladder

Mixed

A combination of urge and stress urinary incontinence (UI) symptoms

Overflow

Occurs with loss of bladder muscle control; incomplete emptying of bladder/retention of urine

Fecal

Inability to control bowel movements; can occur with the passing of gas

Urinary incontinence (UI) is common in people with CF, with prevalence rates that range from 5% to 15% for men and 15% to 76% for women, according to West et al.[1] Urinary incontinence is often prevalent in people with medical conditions, including those with chronic cough and/or diabetes, and, as one gets older, the severity of UI also increases. This may be due to a history of UI and a weak pelvic floor [2,3]

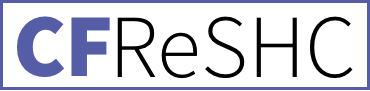

UI in CF is usually stress incontinence, which is triggered by exertions like coughing, physical effort, sneezing, airway clearance, and performing spirometry.[1] People with CF may also experience urge UI, which is the loss of urine during or after a feeling of urgency.[4] Some people experience a mixture of stress UI and urge UI. For women with CF, stress incontinence is most common, and its ability to interfere with doing exercise or performing spirometry successfully is well documented.[1,4–7]

UI can significantly impair an individual’s quality of life.[1,2] It is therefore imperative that clinicians diagnose and address UI, as well as its contributors (e.g., CFRD, constipation, and urinary tract infections), in their treatment plans.[1] Therapies may include learning exercises to strengthen their pelvic floor, using intravaginal mechanical devices, absorbent pads, or training one’s bladder. In severe cases, a patient may have to see a urogynecologist (females) or a urologist (males). More invasive options to treat UI include getting botulinum toxin injections or mid-urethral slings.[1]

While UI is the more common form of pelvic incontinence in CF, some patients do experience fecal incontinence. Fecal incontinence is the occasional leakage of stool while passing gas or the complete loss of bowel control. Fecal incontinence is more common among people who suffer from chronic constipation, a symptom that many people with CF experience [6]. Research among youth with chronic constipation has identified an association with pain, stress, and fecal incontinence, which negatively impacts health-related quality of life [6]. The prevalence of fecal incontinence is unknown in the CF population, however, and thus warrants further research.

- Are you experiencing changes in your urinary and bowel habits, like the urge to urinate at night or urinating multiple times in an hour?

- Women with CF can have urine and/or feces leak when they cough, laugh or do PFTs. What urinary or bowel changes have you noticed?

- Have you ever been treated for incontinence before? If you experience incontinence would you like a referral to a specialist that can help manage that?

- What, if any, changes have you noticed in your urinary or fecal incontinence since starting CFTRm?

- Have you noticed an increase in anxiety and/or depression due to your UI or fecal incontinence?

- Has your UI or fecal incontinence affected your quality of life? If so, how?

PFT Technician to Patient:

- PFT Technician: Ask your patient if they experience incontinence during airway clearance, coughing, or exerting on their PFT.

- PFT Technician: Do you need to use the bathroom before doing your PFT ?

To Any Provider

- What resources can you offer to help me with incontinence?

- I noticed that I am having accidents when I ________________. Is there a provider you recommend who could help me with this problem?

- What can I do now to prevent getting incontinence in the future?

- Since starting CFTRm, I have noticed an improvement in my UI and/or FI. Is this common? What is the cause?

- I am experiencing an increase in my anxiety and/or depression due to UI. What can I do about this?

- My UI and/or FI have started to hurt my daily life. Can you recommend some coping strategies or someone who can help me with this?

What to know about Incontinence

UI symptoms can range from infrequent episodes with a few drops of urine, to more severe symptoms, with leakage occurring several times a day and with enough leakage to require wearing a pad or requiring a clothing change.

CF is characterized by increased cough, altered respiratory mechanics and abnormal posture [2]. Typically, pelvic muscles support the pelvic organs and bladder like a hammock, but the frequent, intense coughing can weaken the muscles surrounding the urethra, vaginal opening, and anus, making them less effective [1]. This is known as pelvic floor dysfunction. In comparing CF coughing patterns to healthy patients with a cold, Dodd and Langman (2012) found that CF coughs have increased intensity and duration, leading to potential incidence of incontinence [2].

Another possible reason for an increased incidence of UI in women with CF is that patients tend to contract their pelvic floor muscles during frequent coughing. They could, therefore, have the tendency to keep pelvic floor muscles chronically contracted, thus weakening them [7].

The occurrence of UI is not directly linked to poor lung function, BMI, CFRD, or the presence of a gastric tube [8]. Furthermore, both child-bearing and non-childbearing women with CF experience UI.

According to West et al., research is currently underway to more precisely characterize UI in women and men with CF and to identify the best treatment options. This information is important because of the necessity of performing effective airway clearance and spirometry and the need to productively cough.[1] With the use of modulator therapy, and its concomitant effect on reducing the frequency of cough, UI rates may decrease among people with CF in the future.

The Impact of UI on the Lives of Women with CF

Incontinence affects both women’s clinic behaviors and their daily lives in numerous ways. For example, patients may not exhale fully during pulmonary function testing to avoid the pressure placed on the pelvic floor muscles in an effort to avoid incontinence. This strategy to avoid urinary incontinence can compromise the “assessment and management of their lung disease” [2]. Likewise, patients may limit airway clearance to avoid leakage. They might also abstain from or reduce exercise, intimacy with a partner, or other potential triggers to avoid leakage, especially if those activities occur in public. Women may also urinate prior to need, limit fluid intake, or change their level of activity so they can stay close to a bathroom [5].

For women with CF, chronic contraction of the pelvic floor during coughing can lead some patients to tighten their vagina, leading to painful sex and other vaginal health conditions. Yet, like other women, the barriers that prevent self-reporting of UI, including stigma, shame, and embarrassment, as well as “perceived bother,” may also prevent patients from seeking treatment for incontinence [5]. In 2001, Orr suggested providers need to develop a “practical and sensitive approach” to address incontinence as part of their routine CF management, but this approach has not yet been widely implemented [3]. With provider and patient education, pelvic incontinence screening for CF patients can increase [3,7,15]. Such efforts are needed because leakage can become progressive and chronic, worsening quality of life.

Treatment options

According to Physical Therapist Beth Taylor, diagnosing pelvic floor dysfunction involves an assessment of symptoms, an internal exam, incontinence education and developing a plan of care [7]. Being overweight, ingesting caffeine, eating spicy food, and drinking alcohol can trigger urinary incontinence (UI) in the general population, as can declining estrogen as females age and enter menopause [3].

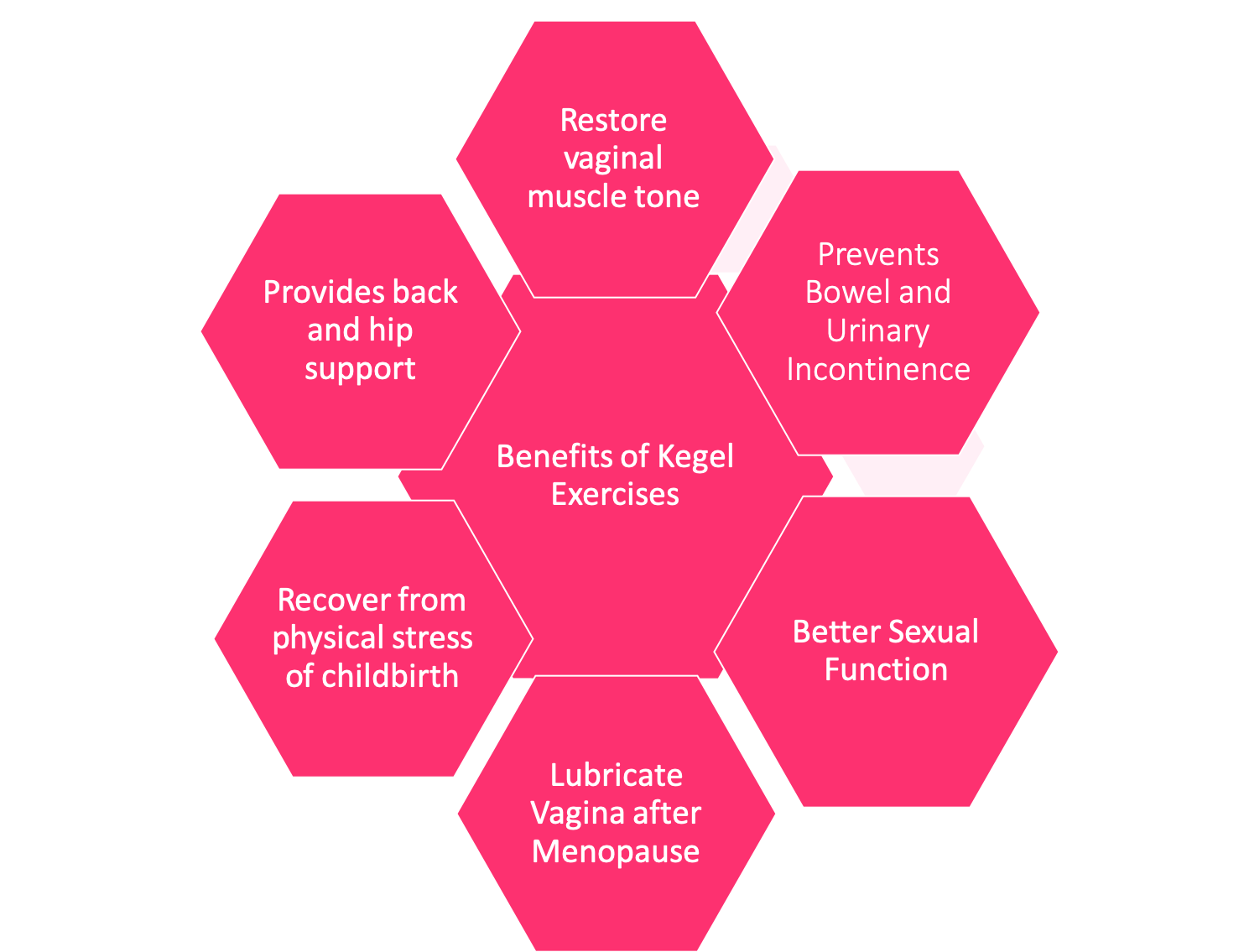

Referral to a gynecologist, urogynecologist, or pelvic floor specialist for patients affected by UI can help expedite treatment. Successful treatment often teaches patients how to properly do “kegel” exercises. Kegels help the patient locate and engage their pelvic floor muscles so that when UI occurs, they can contract these muscles to minimize leakage while coughing and during airway clearance [16]. For women experiencing chronic contraction of pelvic floor muscles, treatment with reverse Kegels might be an option; proper diagnosis and treatment, preferably by a pelvic floor specialist, is necessary [9].

Additionally, physical therapists recommend exercises focusing on improved posture to help relieve UI [15]. Various forms of exercise may also help improve incontinence, including yoga, pilates, and weight training. Medication, biofeedback, electrical stimulation, bladder training, and surgery are all options if PT fails to resolve UI. However, treatment options vary based on the individual patient; what works for one woman may not work for another. This short instructional video of Pilates exercises that address UI may be helpful.

Gaps in knowledge and treatmentThere is no data yet about how reduced cough by patients on CFTR modulators will impact incontinence incidence and prevalence rates. Despite a potential decrease in the incidence rate of urinary incontinence (UI) in patients with CF, these patients may still have weakened pelvic floor muscles. UI could therefore still be present and may require treatment through postural changes, medications, and physical therapy. In addition, there is no data that assesses the prevalence of fecal incontinence (FI); particularly whether it is more common when patients are on antibiotics and experience loose stools.

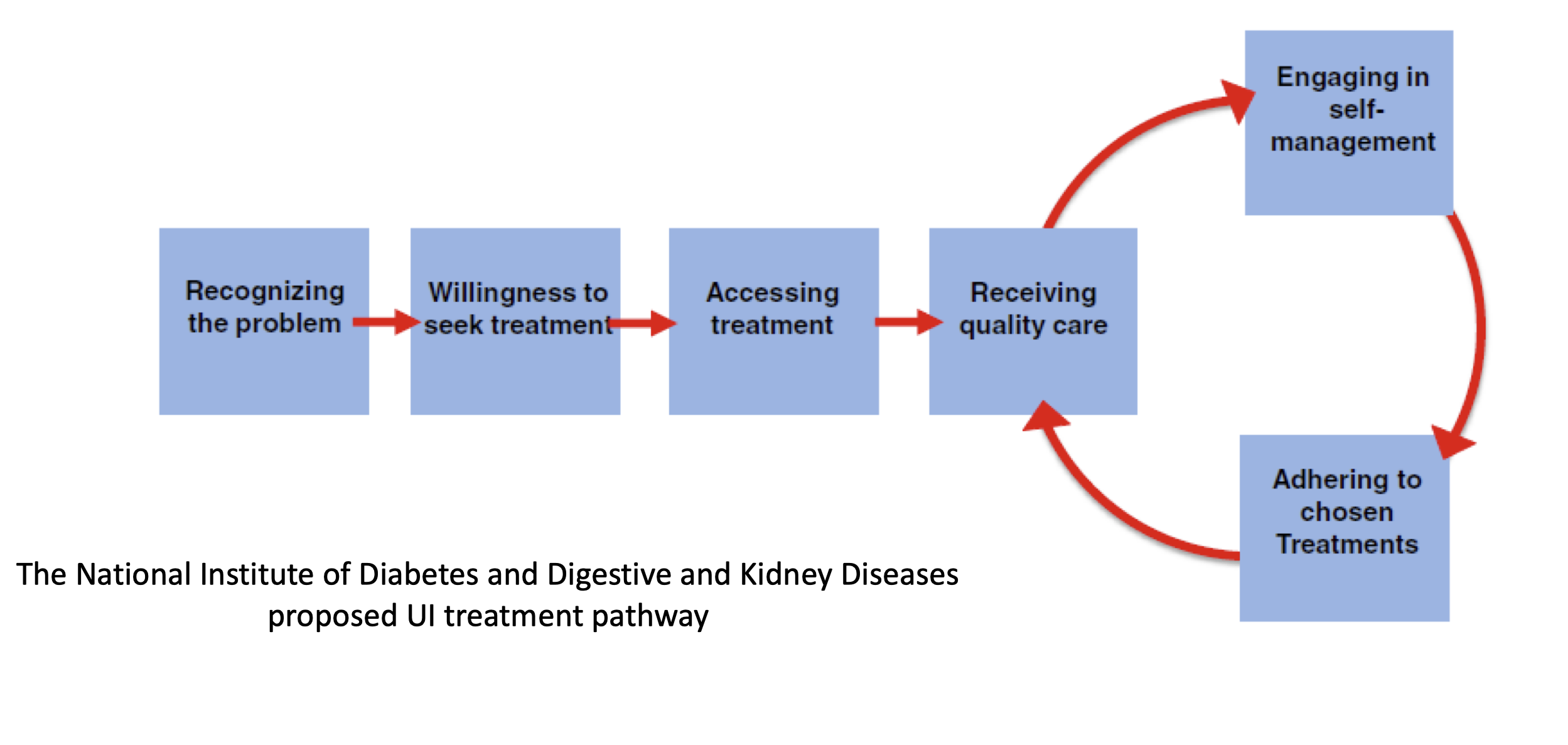

Several years ago, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases convened a workshop spanning two sessions where experts proposed a UI treatment pathway. The pathway (Figure 1) consists of 5 steps women must navigate to successfully address their symptoms.

Operationalizing this pathway through routine discussion and assessment of UI in CF clinical care, provision of psychosocial support, and development of a robust referral system could improve access to UI care for female patients. However, a lack of incontinence management in CF clinical care persists.

Mental Health

Urinary Incontinence (UI) may be a normal part of aging (i.e., it often occurs with perimenopause for women), but it is often embarrassing to those who experience it. For many people, UI can decrease their quality of life and impact their finances and medical status. [4]

Females’ body image and self-esteem can suffer from UI. Nygaard et al. state that an association between depression and incontinence exists amongst middle-aged women [9]. In their exploratory study of middle aged, partnered women (n=57), Saiki and Meize-Grochowski found that psychological health, relationship satisfaction, and relationship dynamics were correlated, no matter the severity of their symptoms [10]. More specifically, UI can cause women to experience a loss of desire, less lubrication, and less sexual satisfaction. Fear of coital urinary incontinence can lead to less frequent sexual activity, more avoidance behaviors, dyspareunia, and abstinence in women with UI [11]. [see the Sexual Function chapter]. UI can also cause women to avoid achieving orgasm for fear of leaking [6]. These behaviors can affect partners and strain intimate relationships, although women who experience them tend to express larger worries than their partners [10, 12-14].

Around the world, UI has been shown to negatively impact people’s mental health.8 Studies on UI in patients with CF conducted in Australia, the UK, Belgium, and Poland have found that UI hurts their social lives, intimacy, family life, holidays, school/work, and relationships.[9] Frayman’s systematic review found that despite the high prevalence of UI among people with CF, few patients share their UI concerns with their CF providers, mostly due to feelings of embarrassment.[9] Men with CF who experience UI have significantly higher scores for anxiety and depression than men with CF but without UI.[10] For men without CF, moderate UI is associated with the highest rates of depression compared to other forms of UI.[1,4,8,10]

Though a significant portion of the female CF population experiences urinary incontinence, UI is under-reported and therefore under-assessed. Despite a hesitancy to discuss UI with their CF team, women report that stress UI negatively impacts their ability to exercise, their social lives, and their sexual relationships.[1,11]

Modulators and Urinary Incontinence

Very little research has been conducted on UI in CF since the emergence of modulator therapy. A study by Van Citters et al. reported that PwCF on modulators showed improvements in lung function, saw fewer hospitalizations, and reduced the number of medications and therapies they took.[12] A majority of the participants reported that, since starting modulators, they had an improved sense of well-being (69 %), an improvement in their overall health (85%), and improved quality of life (79 %).[12] Their physical and well-being were significantly better than those who were not taking modulators or had discontinued the therapy.[12] Nearly half (47 %) of their respondents on modulators also reported a better experience with care.[12] However, people with CF who are not eligible for CFTRm because of their genotype, or those who cannot tolerate it, may feel that the gains in UI-related symptoms for those on modulators are out of reach for them.

therapy. A study by Van Citters et al. reported that PwCF on modulators showed improvements in lung function, saw fewer hospitalizations, and reduced the number of medications and therapies they took.[12] A majority of the participants reported that, since starting modulators, they had an improved sense of well-being (69 %), an improvement in their overall health (85%), and improved quality of life (79 %).[12] Their physical and well-being were significantly better than those who were not taking modulators or had discontinued the therapy.[12] Nearly half (47 %) of their respondents on modulators also reported a better experience with care.[12] However, people with CF who are not eligible for CFTRm because of their genotype, or those who cannot tolerate it, may feel that the gains in UI-related symptoms for those on modulators are out of reach for them.

Vargas’ qualitative study addressed UI in women with CF over 18 on modulators.[3] She and her team asked participants to reflect on their experiences with CF and UI, including symptoms, care-seeking behavior, treatment history and preferences, and the role of their CF health care providers in their UI care.[3]

Five key themes emerged from the Vargas study:

-

- Most women report that their UI symptoms do not interfere significantly with their lives because they prioritize other medical issues. Still, CFTR modulator therapy (CFTRm) has greatly improved UI symptoms because their coughing has decreased.[3]

- Though most women with CF and UI had discussed their UI symptoms with peers or family, they did not seek care because either it was a low priority or because of the stigma.[3]

- Women’s knowledge of UI as a condition that could be treated is very low. They also did not have sufficient knowledge about treatment options. Women with CF were also unaware that UI is comorbid with CF.[3]

- Many women reported that they were hesitant to initiate conversations with their CF providers about UI. Their apprehension limited access to care. Yet most participants said they desired broad screening for UI from their reproductive healthcare team and improved multidisciplinary care relating to UI from their CF clinic.[3]

- Women want access to highly effective UI treatment options with low cost and minimal invasiveness. They desire easily accessible resources as well.[3]

Despite showing improvement in their UI symptoms since starting modulator therapy, Vargas reported that participants may still experience incontinence because of weak pelvic floor muscles that result from a history of chronic cough.[3] Researchers need to conduct further research that investigates the relationship between chronic cough, UI, and modulator use in men and women.[3]

Peer to Peer Advice

- It’s possible to see a pelvic floor physical therapist for incontinence treatment much like doing rehab for a knee injury.

- Using pads specifically designed for incontinence can help if you have symptoms. [Note: incontinence pads are different from menstruation pads or panty liners.]

- After you urinate, stay on the toilet, lean forward and even rock back and forth to make sure all urine is released. Sometimes we think we are done urinating, but the bladder does not empty completely.

- Do not wait to use the restroom but also do not force out urine.

- Download the Squeezy CF app to get information and exercises that may help you (There is a cost for this application).

- Use a device that monitors your Kegels to make sure they are effective. There are free apps to help with Kegel exercises.

- Using the toilet while coughing can help avoid embarrassing urine and/or stool leakage.

- Pay attention to UI symptoms once starting modulators. Report any changes to your provider.

- Schedule regular bathroom breaks to avoid accidents.

- Connect with others who share similar experiences. This can help with managing both emotional and physical challenges.

- Carry extra supplies when out, like pads or a change of clothing, to provide peace of mind.

- See a urogynecologist/urologist to learn if you could benefit from a surgical repair to your bladder or urethra, which can improve function when the pelvic floor has been weakened from chronic coughing.

Resource Links

Beam Feel Good Website.

CF Beyond the Lungs: The Role of Physical Therapy – Karen von Berg, DPT, PT. Presentation at CFRI 2016.

Kenway, Michelle. Pelvic floor physiotherapist, web site:

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction – Beth Taylor, PT. CFReSHC Patient Task Force Meeting Presentation December 10, 2019. [Click here to access presentation video and slides with information sheets on CFReSHC website].

Mayo Clinic. How to do Kegels Properly.

Mayo Clinic. Urinary Incontinence.

Pilates exercises that address UI:

Young Women’s Health. Health Guides. “Cystic Fibrosis: Urinary Incontinence.” Updated 2 Oct 2017.

Works Cited

- Neemuchwala F, Ahmed F, Nasr SZ. Prevalence of pelvic incontinence in patients with cystic fibrosis. Global Pediatric Health. 2017;4:2333794X17743424. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2333794X17743424. doi: 10.1177/2333794X17743424.

- Dodd ME, Langman H. Urinary incontinence in cystic fibrosis. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2005;98 Suppl 45(Suppl 45):28-36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16025765.

- Orr A, McVean RJ, Webb AK, Dodd ME. Questionnaire survey of urinary incontinence in women with cystic fibrosis. BMJ. British medical journal (Clinical research ed.). 2001;322(7301):1521. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11420273.

- CF Reproductive and Sexual Health Collaborative. CFReSHC Snap Poll on Incontinence. 7.27.2020.

- Norton J, Dodson J, Newman D, et al. Nonbiologic factors that impact management in women with urinary incontinence: Review of the literature and findings from a national institute of diabetes and digestive and kidney diseases workshop. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(9):1295-1307. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28674734. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3400-x.

- Klages KL, Berlin KS, Silverman AH, et al. Empirically derived patterns of pain, stooling, and incontinence and their relations to health-related quality of life among youth with chronic constipation. Journal of pediatric psychology. 2017;42(3):325-334. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27474732. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsw068.

- Taylor B. CFReSHC patient task force meeting presentation on incontinence and CF. 12.10.2019.

- Frayman KB, Kazmerski TM, Sawyer SM. A systematic review of the prevalence and impact of urinary incontinence in cystic fibrosis. Respirology. 2018;23(1):46-54. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/resp.13125. doi: 10.1111/resp.13125.

- Nygaard I, Turvey C, Burns TL, Crischilles E, Wallace R. Urinary incontinence and depression in middle-aged United States women. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2003;101(1):149-156. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02519-X. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02519-X.

- Saiki L, Meize-Grochowski R. Urinary incontinence and psychosocial factors associated with intimate relationship satisfaction among midlife women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing. 2017;46(4):555-566. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2017.02.003. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2017.02.003.

- Duralde ER, Rowen TS. Urinary incontinence and associated female sexual dysfunction. Sexual Medicine Reviews. 2017;5(4):470-485. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1931253113. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.07.001.

- Kizilkaya Beji N, Yalcın O, Ayyildiz EH, Kayir A. Effect of urinary leakage on sexual function during sexual intercourse. Urologia Internationalis. 2005;74(3):250-255. https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/83558. doi: 10.1159/000083558.

- Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Jumadilova Z, Bavendam T, Mueller E, Rogers R. Overactive bladder and women’s sexual health: What is the impact? The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2007;4(3):656-666. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00493.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00493.x.

- McPheters JK, Sandberg JG. The relationship among couple relationship quality, physical functioning, and depression in multiple sclerosis patients and partners. Families, Systems, & Health. 2010;28(1):48-68. https://search.datacite.org/works/10.1037/a0018818. doi: 10.1037/a0018818.

- von Berg K. CFReSHC patient task force meeting presentation on incontinence and cystic fibrosis. 5.30.2018.

- Blackwell K, Malone PSJ, Denny A, Connett G, Maddison J. The prevalence of stress urinary incontinence in patients with cystic fibrosis: An under-recognized problem. Journal of Pediatric Urology. 2005;1(1):5-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2004.07.001. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2004.07.001.

Free Printable PDF Download

Want a free printable PDF download of this section for your use in clinic? Just give us your name and email address below to get your download link. This will not add you to our email list.