Hormones

These potent chemical messengers impact many functions within the body.CFReSHC CF-SRH Resource Guide by Patients for Providers and Patients

Key

For Providers

For Patients

For Patients and Providers

Introduction

Hormones are chemical messengers secreted by cells in the body, particularly endocrine glands, which include the pituitary, thyroid, and gonads (ovaries and testes). They transmit messages through the bloodstream or lymphatic system, which regulates many processes in the body’s organs.

Female sex hormones: Estrogen and progesterone influence a woman’s reproductive health, including menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause.

Estrogen promotes the development and maintenance of secondary sexual characteristics and is the primary hormone that drives the growth of the uterine lining before ovulation. It increases muscle mass and regeneration and increases bone density. It increases collagen synthesis but also decreases connective tissue stiffness. It increases fat storage in the breasts, buttocks, and legs but decreases visceral fat storage while having strong anti-obesity effects through regulated energy expenditure. Androgens will only increase sex drive in the presence of estrogen.

Estrogen in excess can also exacerbate anxiety, depression, and headache syndromes and can increase clotting factors. Estrogen is also associated with a pro-inflammatory state and, as such, may have attendant symptoms that are pertinent for women with CF.[1,2]

Estrogen exists in multiple forms throughout the lifespan: estrone (E1) is predominant in menopause, estradiol (E2) and estriol (E3) are most abundant in premenopausal women; estetrol (E4) is only seen during pregnancy. Not much is known about “the different estrogens, their potency, and subsequent metabolism” and how those factors may impact the health of women with CF.[3] However, we know that “all sex steroid hormone receptors have been shown to be expressed in lung tissue.”[3] Further, high levels of testosterone, coupled with low estradiol and progesterone, in non-ovulating female CF patients potentially impact health outcomes.[4] Researchers have shown that estrogen and progesterone impact: “CFTR mRNA expression, the tone of smooth muscle in the airways, airway responsiveness, the immune response, and exhaled nitric oxide (NO),” and changes in the cytology of the tracheobronchial epithelium during the menstrual cycle.[5]

Progesterone is a stabilizing hormone for the uterine lining that peaks in the menstrual cycle’s luteal phase. It is critical for the progression of pregnancy. Progesterone is a metabolic intermediate; the body processes it into many other steroid hormones, such as natural steroids and other sex hormones. It acts as a mild diuretic, relaxes smooth muscle, and decreases inflammation.

Progesterone is also a mood stabilizer, facilitates thyroid hormone action, restores libido in the presence of estrogen and androgens, and helps the body regulate blood sugar levels.[1,2]

Dehydroepiandrosterone-sulfate (DHEA-S) and testosterone, two circulating androgens stable across the menstrual cycle, may enhance lung function. DHEA-S relaxes airway smooth muscle and decreases airway inflammation.

Testosterone also relaxes smooth muscle. It causes specific physiologic changes that may improve CF-related symptoms. Female adolescents with higher testosterone levels in asthma also have higher lung function.[6] In animal models, Researchers have seen testosterone decrease fluid and chloride secretions via CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator). Estrogen has the opposite effect.[7]

Women with CF are not alone when it comes to female sex hormones impacting their disease. For their part, Tam et al. found that estrogen may modulate a variety of lung diseases, causing fluctuations in lung function that vary with their menstrual cycles in women with diseases like COPD, asthma, and CF.[3,5] Researchers do not find this change among women without lung conditions, signaling that circulating estradiol and progesterone may be involved in these pulmonary disease processes.[5] Interestingly, Tam et al. remark that, whereas the highest lung function for women with asthma occurs in the peri-menstrual period, female CF patients experience the highest lung function during the luteal phase and the lowest during the preovulatory phase.[3] Johannesson concurs, finding that FEV₁ was predicted to be 66% in female CF patients during the luteal phase. In comparison, it was only 63% during ovulation, the latter of which is associated with increasing estradiol levels.[5] Although a definitive mechanism is unknown, researchers believe that estradiol may increase mucin production in CF, thereby compromising mucus clearance.[3]

- Have you noticed that your CF symptoms change as you go through your menstrual cycle?

- Some women notice that their CF symptoms change depending on where they are in their cycle. Are you interested in tracking this to identify patterns?

- Are you aware of how your “female” sex hormones may change through your lifespan? Explain to the patient that there are shifts in hormones over the lifespan.

- Be able to offer potential hormonal treatments that may improve health outcomes. (See Contraception chapter)

- I use an application on my phone to track my CF and menstrual symptoms during my menstrual cycle. Can you set aside some time today to discuss my findings?

- What kind of specialist should I see for hormonal issues? Can I get a referral? Do you know an OB/GYN who is knowledgeable about CF?

- Do you have any expertise related to the interaction of CF and female sex hormones?

- Report to your doctor if you notice if lung exacerbations or increased sinus congestion occurs cyclically.

What to Know About Hormones

Hormones are chemical messengers secreted by cells in the body, particularly endocrine glands, which include the pituitary, thyroid, and gonads (ovaries and testes). They transmit messages through the bloodstream or lymphatic system which regulate many processes in different organs of the body.

Female sex hormones: Estrogen and progesterone influence a woman’s reproductive health, including menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause. Estrogen can also cause depression and headaches/migraines, can interfere with thyroid hormones, decrease libido, and impair blood sugar control.

Estrogen is also associated with a pro-inflammatory state and, as such, may have attendant symptoms that are pertinent for women with CF.[1] Progesterone serves as an antidepressant, facilitates thyroid hormone action, restores libido, and regulates blood sugar levels. Testosterone may cause certain symptoms that interact with CF-related symptoms. In animal models, for example, researchers have seen testosterone decrease fluid and chloride secretions via CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator). Estrogen does the exact opposite.[2]

Estrogen exists in multiple forms throughout the lifespan: oestrone (E1) is predominant in menopause, oestradiol (E2) and oestriol (E3) are most abundant in perimenopause; estetrol (E4) is required for pregnancy. Not much is known about “the different oestrogens, their potency and subsequent metabolism” and how those factors may impact the health of women with CF.[3]We do know, however, that “all sex steroid hormone receptors have been shown to be expressed in lung tissue.”[3] Further, high levels of testosterone, coupled with low oestradiol and progesterone, in non-ovulating female CF patients potentially impact health outcomes.[4] Researchers have shown that estrogen and progesterone impact on: “CFTR mRNA expression, the tone of smooth muscle in the airways, airway responsiveness, the immune response, and exhaled nitric oxide (NO),” as well as changes in the cytology of the tracheobronchial epithelium during the menstrual cycle.[5]

Estrogen exists in multiple forms throughout the lifespan: oestrone (E1) is predominant in menopause, oestradiol (E2) and oestriol (E3) are most abundant in perimenopause; estetrol (E4) is required for pregnancy. Not much is known about “the different oestrogens, their potency and subsequent metabolism” and how those factors may impact the health of women with CF.[3]We do know, however, that “all sex steroid hormone receptors have been shown to be expressed in lung tissue.”[3] Further, high levels of testosterone, coupled with low oestradiol and progesterone, in non-ovulating female CF patients potentially impact health outcomes.[4] Researchers have shown that estrogen and progesterone impact on: “CFTR mRNA expression, the tone of smooth muscle in the airways, airway responsiveness, the immune response, and exhaled nitric oxide (NO),” as well as changes in the cytology of the tracheobronchial epithelium during the menstrual cycle.[5]

Women with CF are not alone in female sex hormones impacting their disease. For their part, Tam et al. (2011) found that estrogen may modulate a variety of lung diseases, causing fluctuations in lung function in women with diseases like COPD, asthma, and CF that varies with their menstrual cycles.[3,5] Researchers do not find this change among women without lung conditions, signaling that circulating estradiol and progesterone may be involved in these pulmonary disease processes.[5] Interestingly, Tam et al. remark that, whereas the highest lung function for women with asthma occurs in the peri-menstrual period, female CF patients experience the highest lung function during the luteal phase and the lowest during the pre-ovulatory phase.[3] Johannesson concurs, finding that FEV1 was 66% of predicted in female CF patients during the luteal phase, while it was only 63% during ovulation, the latter of which is associated with increasing levels of estradiol.[5] Although a definitive mechanism is unknown, researchers believe that estradiol may increase mucin production in CF, compromising mucus clearance for female patients.[3]

Gender Disparities

Research has found that females experience more severe disease, poorer clinical outcomes, worsened lung function, and a survival disadvantage compared to their males counterparts across all age groups in CF.[4,6] While these researchers often explain the increased incidence and severity of airway disease in female patients as based upon differences between male and female anatomy, behavior, and hormones, they have not yet found a clear mechanism to explain the presence of sex disparities. Many hypothesize that estrogen may play a significant role.[7] In fact, many researchers believe that the increase in exacerbations in females with CF after the onset of puberty is a direct result of hormone fluctuations during the menstrual cycle.[4,7,8] They have shown that the most potent form of estrogen, 17β-estradiol, plays a prominent part in exacerbating lung function in CF females.[9]

While researchers often explain the increased incidence and severity of airway disease in female patients as based upon differences between male and female anatomy, behavior, and hormones, they have not yet found a precise mechanism to explain the presence of sex disparities. Many hypothesize that estrogen plays a significant role.[9] Sex differences in CF only seem to appear after puberty, so the disparity in morbidity and mortality between the sexes may also be related to post-pubertal hormonal changes.[2] Some researchers believe that the increase in exacerbations in females with CF after the onset of puberty is a direct result of hormone fluctuations during the menstrual cycle.[4,9,10] They have shown that the most potent form of estrogen, 17 β-estradiol, plays a prominent role in exacerbating lung function in CF females.[11] There are also case reports describing increased CF symptoms in transgender women, which is likely related to the estrogen supplementation needed to undergo the transition.[2]

The Gender Gap and Women with CF’s Quality of Life

According to the current knowledge about gender disparities and CF, women tend to have more severe disease progression, more exacerbations and higher mortality rates than their male counterparts [6]. Varied social habits and behaviors between females and males also impact the differential embodiment and progression of the disease. Females perceive their disease differently than males with CF, a fact that can influence their particular response to symptoms and their quality of life [4]. Women often report, for instance, greater concern (physical, social, and emotional) about their career, life expectancy, future success, and body image [4]. Women with CF often participate in fewer physical activities than males with CF, leading to inadequate airway clearance. As opposed to males with CF, some females limit their caloric intake to combat body image issues, an act that can contribute to nutritional deficiency [see Body Image chapter] [4]. As a result, women may feel as if they experience more exacerbations than men, when, in fact, their symptoms are typical CF symptoms. This assessment can negatively affect life activities like maintaining substantial gainful employment, negotiating family building stressors, and having difficulty fulfilling the same societal pressures expected of their non-CF counterparts.

Menstrual Cycle

Varied social habits and behaviors between females and males also impact the differential progression of the disease. Females perceive their disease differently than males with CF, a fact that can influence their particular response to symptoms and their quality of life.[4,12] Women often report, for instance, more significant concerns (physical, social, and emotional) about their career, life expectancy, future success, and body image.[4] Women with CF often participate in fewer physical activities than males with CF, leading to inadequate airway clearance. As opposed to males with CF, some females limit their caloric intake to combat body image issues, an act that can contribute to nutritional deficiency [see Body Image chapter].[4] As a result, women may feel as if they experience more exacerbations than men when, in fact, their symptoms are typical CF symptoms. This assessment can negatively affect life activities like maintaining substantial gainful employment, negotiating family-building stressors, and having difficulty fulfilling the same societal pressures expected of their non-CF counterparts.

Hormones During the Menstrual Cycle

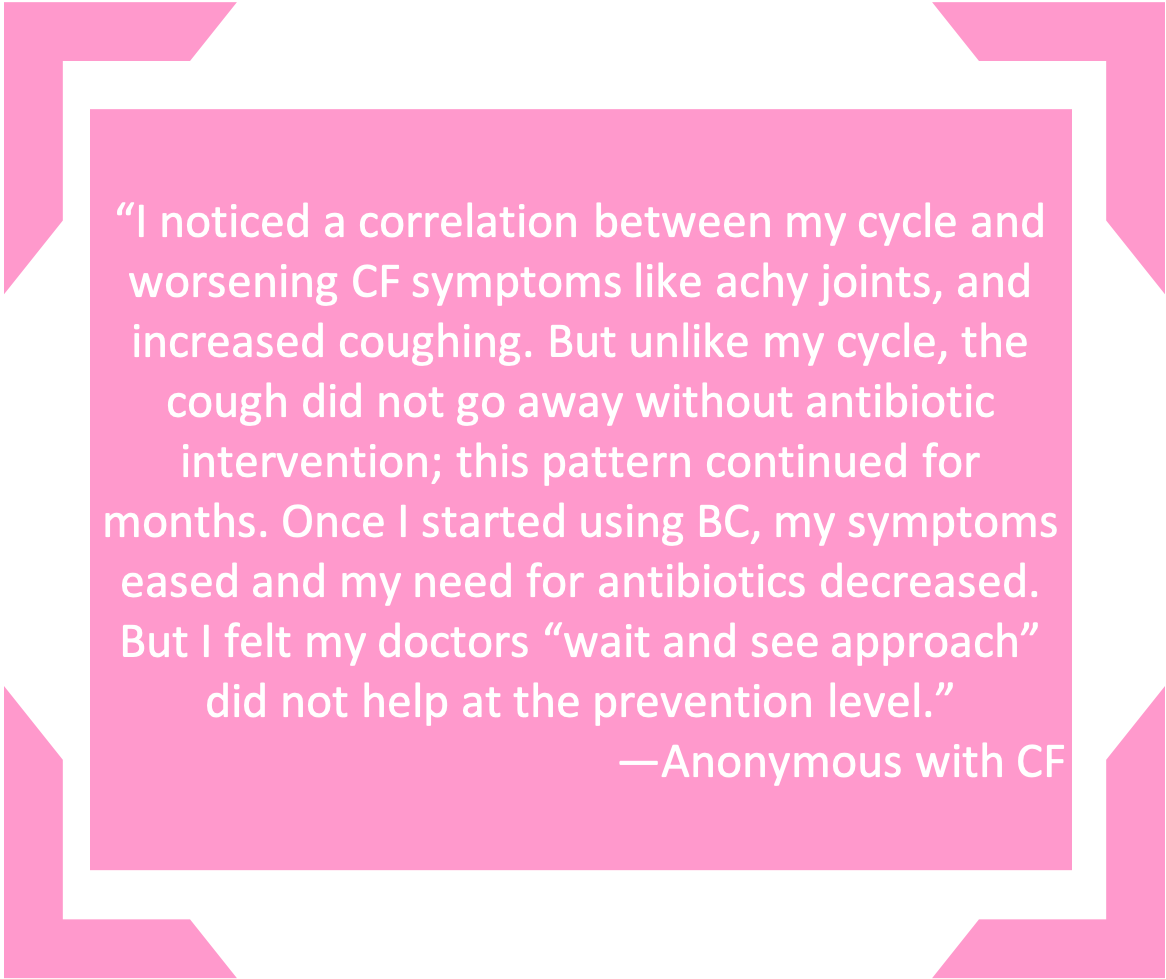

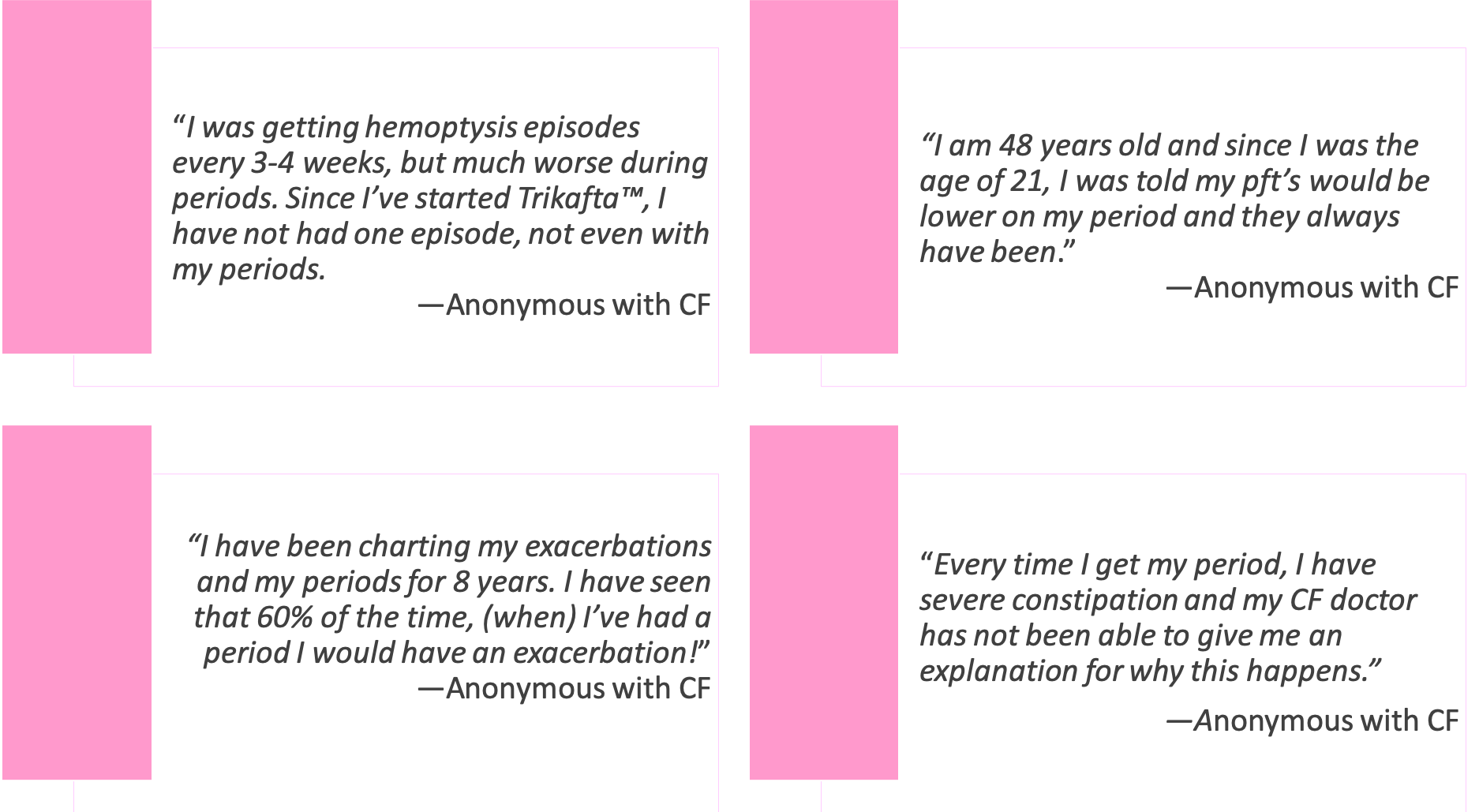

During the CFReSHC Patient Task Force meeting on hormones, women with CF indicated that problems with female sex hormones were of great concern to them. They noticed that patterns of CF symptoms, like increased coughing and mucus production, correlate with their menstrual cycles.[13] Many women with CF have connected their periods to pulmonary exacerbations, but few studies have looked extensively at this issue. Godfrey and Sufian (co-founders of the CF Reproductive and Sexual Health Collaborative) studied the CF symptom-menstruation link, asking participants to track their CF symptoms to see if there are indeed menstrually-related patterns and to discern which symptoms most commonly occur among women.[12,14] After initiating Trikafta™, females experienced decreased pulmonary symptoms overall. Still, they noticed a shift to gastrointestinal symptoms with hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle.[12,14,15]

Other researchers have noted the connection between pulmonary congestion and the menstrual cycle in CF. Coakley et al., for instance, suggest that for about one week of a 4-week menstrual cycle, women with CF seem to have a reduced ability to efficiently clear airway secretions.[16] According to Vidaillac et al., “the role of hormones as modulators of CF disease is further suggested by fluctuating lung function and nasal potential differences throughout a menstrual cycle.”[4] The authors assert that “further work dissecting out mechanisms through which sex steroids regulate host physiology and bacterial pathogenicity” is needed.[4]

Clinical studies have pointed to increased levels of estrogen as a primary culprit for patterned CF symptoms. Not only do increased levels of estradiol correlate with more lung exacerbations during the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, but they are also thought to cause the conversion of P. aeruginosa to its more virulent mucoid form. The latter compromises lung function.[17] In addition to showing evidence of such conversion, Chotirmall et al. analyzed data from the Cystic Fibrosis Registry of Ireland, finding that women who took oral contraceptive pills needed fewer antibiotics compared to those who did not take oral contraceptives.[11] Further research is required to confirm this finding.

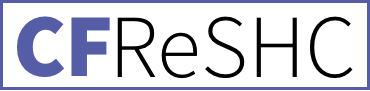

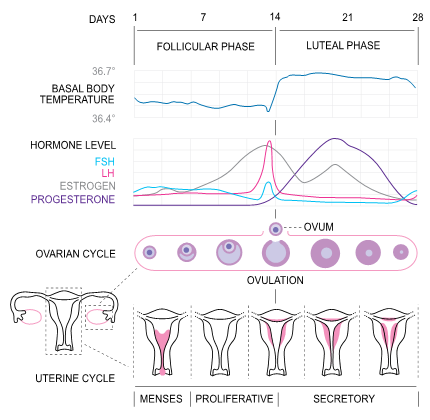

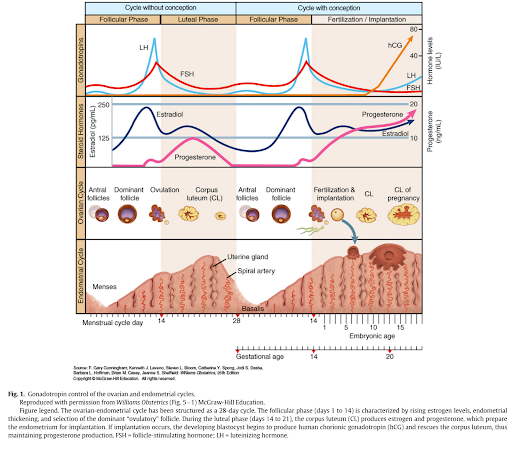

To understand the clinical changes seen in CF symptoms across the menstrual cycle, the typical patterns of changes in estrogen and progesterone need to be understood. At the start of menstruation (day 1), the levels of both estrogen and progesterone are low. Estrogen levels rise and peak as the follicle grows (follicular phase). Estrogen decreases dramatically with ovulation, while progesterone begins to increase. During the luteal phase (after ovulation), progesterone levels peak while estrogen begins to rise. Both hormones drop precipitously to start the monthly bleed.[2]

Figure 1: Hughan K, Daley T, Socorro Rayas M, Kelly A, Roe A. Female reproductive health in cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2019;18:S96.

A review by Lam et al. describes the link between menstrual physiology and CF throughout the menstrual cycle. During menstruation, when the estrogen and progesterone levels are low, FEV₁ and FVC are also usually low. During the follicular phase, when estrogen levels peak and are at their highest, pseudomonas converts to its mucoid form, and pulmonary exacerbations increase. During ovulation, airway inflammation peaks, the pseudomonas load increases, FEV₁ and FVC decrease, and pulmonary exacerbations are high. During the luteal phase, when progesterone peaks and estrogen enjoys a smaller peak, inflammation decreases, FEV₁ and FVC return to the pre-menstrual baseline, and pseudomonas returns to its non-mucoid form.[2]

Estrogen increases secretion viscosity, increases mucin production, decreases chloride ion secretion, increases plugging, and decreases ciliary beat intensity, making it more difficult to clear the airways. Estrogen also increases viral immunity but decreases the immune response to bacteria and decreases bacterial clearing. Estrogen enhances the growth of pseudomonas and promotes the conversion to the mucoid form.[2]

Little is known about progesterone’s role in inflammation and infection in CF. In other conditions, progesterone decreases the immune response and decreases inflammation. It reduces cellular lung damage, improves lung function after influenza infections, and may promote some immune defense memory in mouse models.[2]

Compared to the non-CF population, testosterone levels are no different in CF, but DHEA-S levels are lower. It is unclear what clinical outcomes low DHEA-S might produce, but low DHEA-S may be contributing to increased inflammation seen in females with CF.[2]

Figure 2: Lam G, Goodwin J, Wilcox P, Quon B. Sex disparities in cystic fibrosis: review on the effect of female sex hormones on lung pathophysiology and outcomes. European Respiratory Society Open Research. 2021;7:3.

Hemoptysis and Female Sex Hormones

Catamenial hemoptysis is when a female experiences hemoptysis with menstruation. It is a clinical manifestation of thoracic endometriosis syndrome (TES) and is commonly treated with hormonal therapy.[1] While catamenial hemoptysis is considered rare in the general population, clinicians and patients have reported a connection between hormones, CF, and hemoptysis.

Extant literature indicates that hemoptysis affects men and women equally. There

are no discernable patterns in how and when it appears in CF patients (beyond age and lung deterioration). However, CFReSHC patient partners believe that further study is needed on this particular issue because some females with CF report hemoptysis during certain phases of their menstrual cycle.

In a case report of a woman on Symdeko™ and then Trikafta™, Montemayor et al. suggest that when a female reports hemoptysis, providers need to gather a menstrual history because “a patient’s underlying clinical presentation and symptoms can be diagnostic of TES, and extensive diagnostic work-up may not be needed.”[1] Further, Montemayor remarks that females with CF who have catamenial hemoptysis and have a genetic mutation approved for Symdeko™ or Trikafta™ can be managed effectively with either of these CFTR modulators alongside hormonal contraceptive therapy.[1] Still, much more research on CF and catamenial hemoptysis is needed.

Other Hormones Affecting Women with CF

Delayed puberty was once considered a common problem in CF. However, recent reports now indicate that individuals with CF generally show that the gap between pubertal development in adolescents with CF is now consistent with their peers.20 This is likely due to improved treatments.

Recent data suggests that bone age but not Tanner staging or age of menarche differed between females with CF and the general population.[23] Most notably, individuals with CF often have an absence of the pre-adolescent growth spurt and lower peak height velocity.[20,23] It remains crucial to evaluate pubertal development for “linear growth, bone mineral accrual, body image, and psychosocial wellbeing,” which CF can influence.[20] Because researchers have found that “patients with poorly controlled diabetes and CF-related liver disease are predisposed to malnutrition and may be at higher risk of abnormal pubertal development,” they suggest clinicians evaluate the endocrine system to “avoid exacerbating potential problems such as poor body image, sub-optimal linear growth, and compromised peak bone mass.”[20]

Studies comparing adolescents with CF and the general population suggest that pubertal delay is linked to malnutrition rather than an intrinsic feature of the disease. Since growth hormone stimulates pubertal growth and helps regulate body composition, muscle, bone growth, and sugar and fat metabolism, growth hormone therapy can improve the intermediate outcomes of height, weight, and lean tissue mass.[20]

CFTR, expressed in the hypothalamus and the pituitary glands, may also impact pubertal development. Modulator therapy may help normalize pubertal development in patients with CF who can take these therapies, but this association remains to be seen.[19,23]

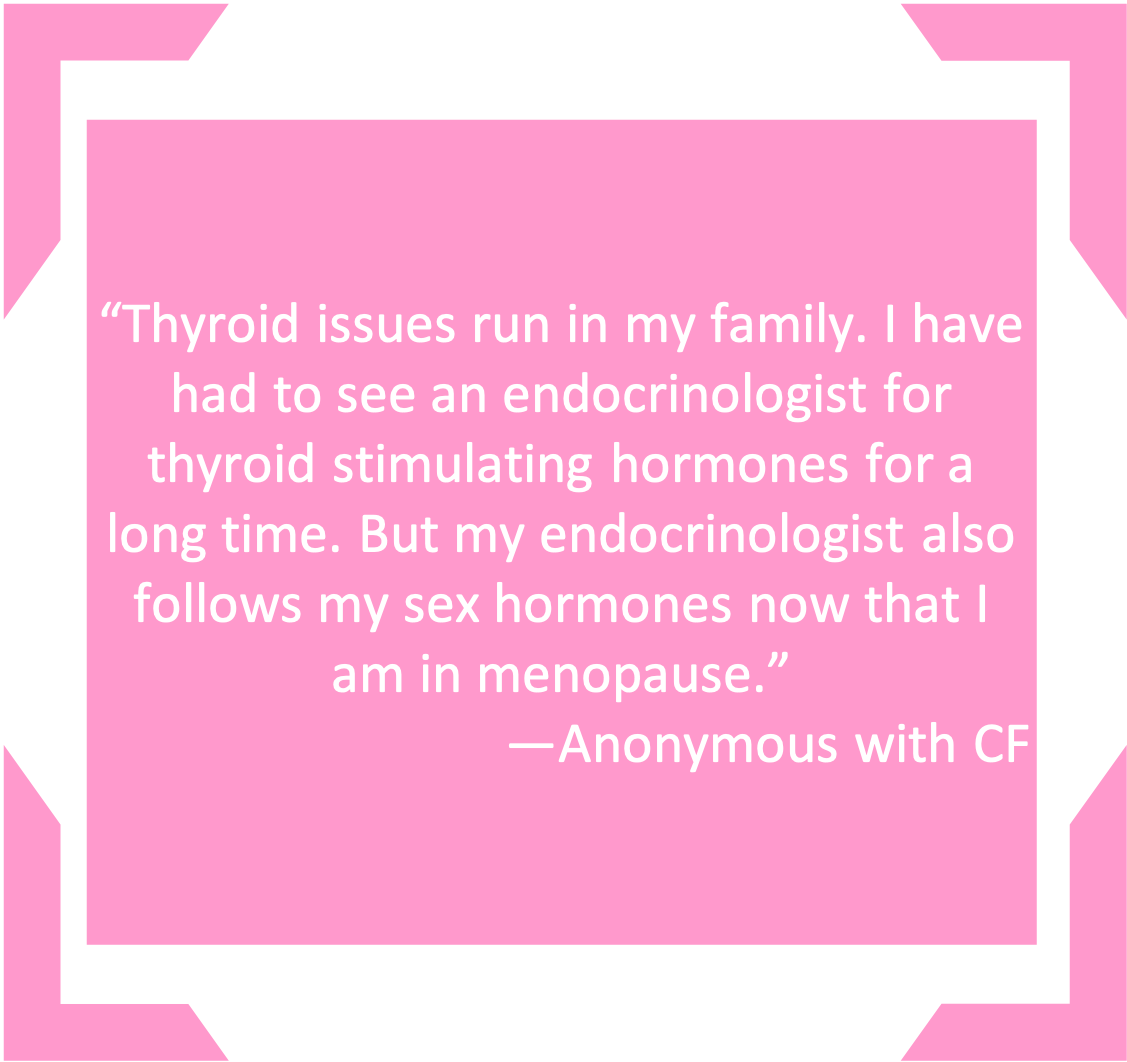

Thyroid

The thyroid impacts the basal metabolic rate and protein synthesis. It also regulates long bone growth (along with the growth hormone). Hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can negatively impact reproductive health by reducing rates of conception and raising the chances of early pregnancy loss.

Thyroid issues in women with CF have not been adequately explored. In a study looking at CF patients in Germany, Lutz Naehrlich et al. demonstrated that high levels of iodine deficiency can lead to subclinical hypothyroidism. As such, some patients with CF may require iodine supplementation to assist with thyroid function.[18]

The CTFR is expressed in the hypothalamus and the pituitary glands, which are crucial glands that modulate thyroid hormone production. Modulator therapy may improve hypothalamic thyroid regulation. However, that connection has yet to be proven.[19,20]

Insulin

The pancreas produces insulin, an essential hormone that regulates blood sugar levels. Insulin and glucose metabolism play a role in fertility and other reproductive processes. CF-related diabetes (CFRD) is common and is seen in 30% of adults compared with <6% of children.[21] Olesen et al. found that the prevalence of CFRD increases with age; it is also associated with chronic gram-negative infection, poor lung function, and low BMI.[22] They also found that “severe genotype, pancreatic insufficiency, and female gender remain considerable intrinsic risk factors for early acquisition of CFRD.”[22] Overall, CFRD is associated with lung infections, lower lung function, and poor nutritional status, making “early diagnosis and aggressive treatment of CFRD more important than ever with increasing life span.”[22] The primary issue in CFRD is insulin secretion is reduced and delayed. Insulin resistance can cause CFRD, especially in an aging CF population. Because insulin deficiency is the primary issue, insulin therapy is the mainstay of treatment. Whether partial restoration of CFTR function by modulator therapy can prevent or reverse CFRD remains to be seen. Chin et al. report that four months of ivacaftor therapy improved insulin secretion in patients with normal to mildly impaired glucose tolerance.[21]

Hormones & Development

Delayed puberty was once considered a common problem in CF. However, recent reports now indicate that individuals with CF generally show that the gap between pubertal development in adolescents with CF is now consistent with their peers.[20] This is likely due to improved treatments.

Recent data suggests that bone age but not Tanner staging or age of menarche differed between females with CF and the general population.[23] Most notably, individuals with CF often have an absence of the pre-adolescent growth spurt and lower peak height velocity.[20,23] It remains crucial to evaluate pubertal development for “linear growth, bone mineral accrual, body image, and psychosocial wellbeing,” which CF can influence.[20] Because researchers have found that “patients with poorly controlled diabetes and CF-related liver disease are predisposed to malnutrition and may be at higher risk of abnormal pubertal development,” they suggest clinicians evaluate the endocrine system to “avoid exacerbating potential problems such as poor body image, sub-optimal linear growth, and compromised peak bone mass.”[20]

Studies comparing adolescents with CF and the general population suggest that pubertal delay is linked to malnutrition rather than an intrinsic feature of the disease. Since growth hormone stimulates pubertal growth and helps regulate body composition, muscle, bone growth, and sugar and fat metabolism, growth hormone therapy can improve the intermediate outcomes of height, weight, and lean tissue mass.[20]

CFTR, expressed in the hypothalamus and the pituitary glands, may also impact pubertal development. Modulator therapy may help normalize pubertal development in patients with CF who can take these therapies, but this association remains to be seen.[19,23]

Female Sex Hormonal Symptoms and Knowledge Gaps

Researchers and women with CF are increasingly linking CF symptoms like fatigue, headaches, weight gain/loss, GI issues, depression, brain fog, or increased coughing to fluctuations in female sex hormones.[8,24] Some women, for instance, complain of monthly lung exacerbations that correspond with their menstrual cycles.[25] In these cases, the provider may need to evaluate a patient’s observations further and offer creative therapeutic options. Some providers have begun to treat cyclical CF symptoms by prescribing birth control pills to see if they can help relieve pulmonary symptoms, as Chotirmall’s study suggests.[17] Some women have tried increasing the frequency of nebulizer treatments and airway clearance during the luteal phase to see if that prevents symptoms.[25] Besides pulmonary symptoms, GI symptoms may change with hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle. Since cells lining the gastrointestinal tract have estrogen and progesterone receptors, these hormones may also affect women’s gastrointestinal function, including motility.[26] Adjusting a woman’s enzyme dose to respond to GI changes throughout the menstrual cycle may alleviate cyclic worsening of GI symptoms and absorption. However, this has not yet been studied in the CF population.[25] Without known effective therapies to treat the interaction of CF symptoms with hormonal fluctuations, these approaches may be an excellent place to begin management strategies. More studies are needed to discern if hormonal birth control, shifts in enzyme dosages, or other modalities are effective in reducing symptoms for the majority of women.

Changing sleep patterns and fatigue are essential manifestations of both physical and mental health and can be related to CF, hormonal issues, or the intersection of both. However, it is difficult to discern if and when fatigue and sleep disruptions are caused by fluctuating female sex hormones, CF, or their interaction. Fatigue can affect a woman’s work and family obligations and sleep patterns.[27] Sleep issues in CF, in turn, can negatively impact a woman’s adherence to her CF treatment routines. Addressing these symptoms and their cyclical nature is vital to ensure the health and well-being of women with CF.

Hormonal changes not only affect physical symptoms but also mental ones. According to CFReSHC’s Patient Task Force, the interaction of hormonal fluctuations and CF can exacerbate feelings of anxiety and depression.[25] Which management strategies (medication, counseling, meditation, etc.) will be most helpful in relieving mental symptoms is unknown but worthy of serious inquiry. Due to the complexity of mental health management, these treatment approaches will likely need to be highly individualized for each patient.

Menopause can bring with it many issues, including mood changes, heat and cold intolerance, night sweats, sleep disturbances, palpitations, joint pain, fatigue, cognitive decline, vaginal dryness, pain with intercourse, sexual dysfunction, and worsening CF symptoms. Menopausal symptoms often overlap or amplify preexisting CF-related symptoms.[19,28] Wu et al. demonstrated that women with CF who took hormonal therapy had higher quality of life scores in physical functioning, vitality, treatment burden, role limitations, weight, respiratory symptoms, and digestion symptoms. Notably, all 26 women in this study were using a combination of estrogen and progesterone.[29] (See Menopause chapter).

Hormones & Mental Health

Some reports indicated that starting modulator therapy can exacerbate mental health issues such as depression and anxiety and create cognitive impairment. These symptoms generally can be alleviated with dose adjustments of either the modulator or the mental health medications.[30–32] Whether management of depression and anxiety through antidepressants and oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) can alleviate some of the side effects of modulators for females with CF remains a topic for future research. This approach has been studied as a way to manage premenstrual depression.[33] It remains to be seen if a similar treatment approach for the iatrogenic mood effects of modulators can be taken.

Psychosocial Aspects and Patient-Provider Trust

Given the lack of definitive knowledge about female sex hormones and CF symptoms in the past, patients have had to press their providers to consider this connection. This dynamic may be based on scientific knowledge gaps and gender stereotypes. Such stereotypes can cause females to doubt their intuition about their bodies and can lead some providers to dismiss their observations. For example, some CFReSHC patient-partners reported that some providers questioned their hormonal symptoms and concerns. Others stated that their providers hesitated to believe them; they did not see questions about CF and hormones as valid.[13,25]

The stigma surrounding the topic of hormones can prevent females with CF from discussing noticeable patterns with their CF providers or from asking questions about their menstrual periods. According to CFReSHC’s patient partners, females with CF might delay a gynecological appointment if their provider views such symptoms as only CF-related rather than the interaction of CF symptoms and the menstrual cycle. Moreover, a lack of knowledge, feelings of low self-esteem, and having a low body image may prevent a female patient from seeking medical care or from inquiring about a noticed or changed symptom.[25] Menstrual periods and mood fluctuations can evoke shame and secrecy, causing women to downplay or avoid paying attention to cyclical health patterns. This stigma can be compounded if her/their doctor fails to take the patient’s observations or questions seriously.

Females with CF view their CF team as their primary care providers and prefer to receive reproductive health counseling from their CF team and desire defragmented, coordinated care.[34,35] Participants in the study by Leech et al. voiced the concern that their reproductive health providers did not understand CF well enough to provide helpful care to a patient. One participant stated, “OB/GYNs don’t have enough knowledge of CF to really have a valuable input.”[35]

Another participant, in an article by Jain et al., reported:

Sexual, reproductive, and general women’s health care has been largely ignored by my CF teams. In my experience, CF teams are rarely comfortable with topics such as birth control and pregnancy. I am always told to consult a primary care doctor or obstetrician, or gynecologist. These providers do not know enough about CF or the myriad of medications I take. They seem terrified to wade into the care of a woman with a chronic disease as complex as CF. Everything I have learned about safe and effective contraceptive options, pregnancy, and parenthood as a woman with CF has been acquired through my own research or by speaking with and listening to other women with CF. Until our caregivers can either collaborate or educate themselves on these issues, women with CF will continue to muddle through these topics, relying on each other to share our stories and give each other guidance and support.[6]

These issues put females with CF in the role of needing to self-advocate for comprehensive CF-informed hormonal care and to serve as the bridge that connects their disparate providers.

Peer to Peer Advice

- You may need to see a specialist beyond your CF provider to test or monitor your hormone levels, but be aware that since female hormones fluctuate a great deal across the menstrual cycle, so menstrual-related issues can be best evaluated by a detailed history and symptom-focused cycle tracking in addition to laboratory values.

- You can track your symptoms on a free period tracker app (even if you do not have a period) to show your provider any patterns that such tracking reveals. [12,36]

- Be your own advocate! Keep asking questions and seeking opinions from different providers.

- Find an online group of women with CF, like those in CFReSHC, that you can talk to about your symptoms. Join the private CFReSHC Facebook group.

- Listen to your body: get rest when needed.

- Inquire about the possible benefits of a continuous glucose monitor for CFRD and its interaction with menstruation.

Works Cited

- Montemayor K, Claudio AT, Carson S, Lechtzin N, Christianson MS, West NE. Unmasking catamenial hemoptysis in the era of CFTR modulator therapy. J Cyst Fibros J Cyst Fibros. 2020;19(4):e25-e27. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2020.01.005

- Lam GY, Goodwin J, Wilcox PG, Quon BS. Sex disparities in cystic fibrosis: review on the effect of female sex hormones on lung pathophysiology and outcomes. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(1):00475-02020. doi:10.1183/23120541.00475-2020

- Tam A, Morrish D, Wadsworth S, Dorscheid D, Man SFP, Sin DD. The role of female hormones on lung function in chronic lung diseases. BMC Womens Health BMC Womens Health. 2011;11(1):24. doi:10.1186/1472-6874-11-24

- Vidaillac C, Yong VFL, Jaggi TK, Soh-Min-Min, Chotirmall SH. Gender differences in bronchiectasis: a real issue? Breathe. 2018;14(2):108-121. doi:10.1183/20734735.000218

- Johannesson M, Ludviksdottir D, Janson C. Lung function changes in relation to menstrual cycle in females with cystic fibrosis. Respir Med. 2000;94(11):1043. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-54794

- Jain R, Kazmerski TM, Aitken ML, et al. Challenges Faced by Women with Cystic Fibrosis. Clin Chest Med. 2021;42(3):517-530. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2021.04.010

- Mokhtar HM, Giribabu N, Kassim N, Muniandy S, Salleh N. Testosterone decreases fluid and chloride secretions in the uterus of adult female rats via down-regulating cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) expression and functional activity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;144 Pt B:361-372. doi:S0960-0760(14)00186-1 [pii]

- Harness-Brumley CL, Elliott AC, Rosenbluth DB, Raghavan D, Jain R. Gender Differences in Outcomes of Patients with Cystic Fibrosis. J Womens Health Larchmt N 2002. 2014;23(12):112-1020. doi:10.1089/jwh.2014.4985

- Zeitlin PL. Cystic fibrosis and estrogens: a perfect storm. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(12):3841-3844. doi:10.1172/JCI37778

- Sutton S, Rosenbluth D, Raghavan D, Zheng J, Jain R. Effects of puberty on cystic fibrosis-related pulmonary exacerbations in women versus men. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49(1):28-35. doi:10.1002/ppul.22767

- Saint-Criq V, Harvey BJ. Estrogen and the cystic fibrosis gender gap. Steroids. 2014;81:4-8. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2013.11.023

- Sufian S, Mueller R, Langfelder-Schwind E, et al. When chronicity meets cyclicity: The cultivation of embodied knowledge and selfhood by cis-gender women with cystic fibrosis. SSM – Qual Res Health. 2024;5:100412. doi:10.1016/j.ssmqr.2024.100412

- Reproductive CF, Collaborative SH. CFReSHC Patient Task Force Meeting on Hormones and Cystic Fibrosis. In; 2018.

- Godfrey E, Walker P, Ruben M, et al. 569 Symptom changes throughout the menstrual cycle in women with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22:S300-S301. doi:10.1016/S1569-1993(23)01491-1

- Godfrey E, Sufian S. MENstrual Symptom TRacking to Understand and Assess (Women) Living with CF. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Clinical Pilot and Feasibility Grant.; 2020.

- Coakley RD, Sun H, Clunes LA, et al. 17β-Estradiol inhibits Ca2+-dependent homeostasis of airway surface liquid volume in human cystic fibrosis airway epithelia. J Clin Invest. 2008;118(12):4025-4035. doi:10.1172/JCI33893

- Chotirmall SH, Smith SG, Gunaratnam C, et al. Effect of Estrogen on Pseudomonas Mucoidy and Exacerbations in Cystic Fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1978-1986. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1106126

- Naehrlich L, Dörr HG, Bagheri-Behrouzi A, Rauh M. Iodine deficiency and subclinical hypothyroidism are common in cystic fibrosis patients. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2013;27(2):122-125. doi:10.1016/j.jtemb.2012.08.002

- Hughan KS, Daley T, Rayas MS, Kelly A, Roe A. Female reproductive health in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2019;18 Suppl 2:S95-S104. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.024

- Goldsweig B, Kaminski B, Sidhaye A, Blackman SM, Kelly A. Puberty in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18:S88-S94. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.013

- Chin M, Brennan AL, Bell SC. Emerging Nonpulmonary Complications for Adults With Cystic Fibrosis: Adult Cystic Fibrosis Series. Chest. 2022;161(5):1211-1224. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2021.11.001

- Olesen HV, Drevinek P, Gulmans VA, et al. Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes in Europe: Prevalence, risk factors and outcome; Olesen et al. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;19(2):321-327. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2019.10.009

- Roe AH, Merjaneh L, Oxman R, Hughan KS. Gynecologic health care for females with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2021;26:100277. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100277

- Jain R, Sabanova V, Holtrop M, et al. Effects of sex hormones on markers of health in Women with Cystic Fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. Published online 2019:221.

- Reproductive CF, Hormones SHC on. CFReSHC Patient Task Force on Hormones. Published online April 29, 2020.

- Hogan AM, Collins D, Baird AW, Winter DC. Estrogen and its role in gastrointestinal health and disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24(12):1367-1375. doi:10.1007/s00384-009-0785-0

- Han MK, Arteaga-Solis E, Blenis J, et al. Female sex and gender in lung/sleep health and disease: Increased understanding of basic biological, pathophysiological, and behavioral mechanisms leading to better health for female patients with lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(7):850-858. doi:10.1164/rccm.201801-0168WS

- Prochownik K, Jain R, Taylor-Cousar J, et al. Menopause in people with cystic fibrosis. Menopause N Y N Menopause. Published online 2023. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000002155

- Wu M, Arora N, Sueblinvong V, Hunt WR, Tangpricha V. Use of estrogen supplementation is associated with higher quality of life scores in women with cystic fibrosis. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2022;27:100292. doi:10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100292

- Talwalkar JS, Koff JL, Lee HB, Britto CJ, Mulenos AM, Georgiopoulos AM. Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator Modulators: Implications for the Management of Depression and Anxiety in Cystic Fibrosis. Psychosom Wash DC. 2017;58(4):343-354. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2017.04.001

- Heo S, Young DC, Safirstein J, et al. Mental status changes during elexacaftor/tezacaftor / ivacaftor therapy. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2022;21(2):339-343. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2021.10.002

- Landau EEC. Cystic fibrosis in a transformative era: Adapting to changing mental health needs. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2023;22(3):372-373. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2023.05.002

- Joffe H, Petrillo LF, Viguera AC, et al. Treatment of premenstrual worsening of depression with adjunctive oral contraceptive pills: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry. 68(12).

- Kazmerski TM, Stransky OM, Lavage DR, et al. Sexual and reproductive health experiences and care of adult women with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22(2):223-233. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2022.09.013

- Leech MM, Stransky OM, Talabi MB, Borrero S, Roe AH, Kazmerski TM. Exploring the reproductive decision support needs and preferences of women with cystic fibrosis. Contracept Stoneham Contracept. 2021;103(1):32-37. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.10.004

36. Godfrey E, Brown G, Caldwell K, et al. WS02.03 Correlating menstrual cycles and cystic fibrosis symptoms among women with cystic fibrosis in the era of highly effective modulators: early findings of the MENSTRUAL study. J Cyst Fibros. 2023;22:S4-S4. doi:10.1016/S1569-1993(23)00195-9

Free Printable PDF Download

Want a free printable PDF download of this section for your use in clinic? Just give us your name and email address below to get your download link. This will not add you to our email list.