Pregnancy in Women with CF

As more women with CF become pregnant, they face complicated decisions about whether and how to navigate the processCFReSHC CF-SRH Resource Guide by Patients for Providers and Patients

In this section:

- Introduction

- Priority Questions

- Preparing for Pregnancy

- Medications

- Modulators

- Genetic Counseling

- Transplant

- During Pregnancy

- Pregnancy Loss

- Labor and Delivery

- Postpartum

- Breastfeeding

- Social Support

- Maintaining Health

- Emotional Health

- Patient Perspective

- Peer-to-Peer Advice

- Resource Links

- Works Cited

Key

For Providers

For Patients

For Patients and Providers

Introduction

The number of pregnancies and successful deliveries among women with CF continues to rise as women with cystic fibrosis live longer lives, and as scientific advances improve their health and quality of life. Because of the inherent risks of pregnancy, women with CF should ideally undergo pre-pregnancy planning with their CF clinic 3–6 months in advance of conception to help guide them through this process. CF clinic providers can advise women on pregnancy health risks and the potential for complications, and then make referrals to an experienced OB/GYN, maternal-fetal medicine specialist, and/or genetic counselor.

While females with CF are generally considered fertile and capable of becoming pregnant, some factors can affect their fertility. These include thick, dehydrated, pH-imbalanced cervical mucus, delayed puberty and ovulation, and suboptimal nutritional status.[1] With the advent of highly effective modulator therapy (HEMT) use, the fertility of females with CF has improved because the medication increases general health and nutritional status and improves cervical mucus viscosity.[1]

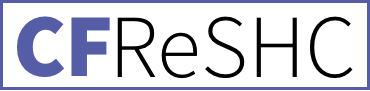

Even before the age of HEMT, the number of pregnancies and successful deliveries among females with CF continued to rise.[2] With scientific advances in managing CF, females’ health and quality of life have improved, leading to longer lives.

With appropriate planning and monitoring in place, maternal and fetal outcomes for women with CF are generally positive.[3] While studies evaluating the safety and health outcomes of pregnancy in women with CF are limited, recent findings indicate that pregnancy does not typically lead to a decline in health.[4,5] Still, there are some risks of pregnancy for this population, so females with CF should ideally engage in pre-pregnancy planning with their CF clinic about 3–6 months before conception to assess their readiness and feasibility of pregnancy. CF clinic providers can advise females on pregnancy’s health risks and potential complications and make referrals to an experienced OB/GYN, maternal-fetal medicine specialist, and/or genetic counselor.

Source: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry, 2022

- What are your reproductive goals?

- When planning for pregnancy/during pregnancy:

- How do you feel about your delivery plan, and do you have the information you need about the different possible outcomes?

- What birth control method would you like to use once you have your baby?

- Can you describe your support system? Who could help you balance childcare with treatments?

- During and after pregnancy:

- How are YOU (not baby) doing emotionally/mentally?

- Have you experienced any changes to your vaginal health or your pelvic floor function?

- Recommendation: Have conversations about CF-specific needs like medications, maintaining airway clearance, and how to modify routine(s) while caring for a baby and potentially breastfeeding.

- Can I create a written care plan for you to share with your OB-GYN or MFM to outline your CF care needs during labor and delivery?

- What are the risks to my health if I opt to get pregnant? How do you feel my health will be impacted if I get pregnant?

- Would you support my decision to stay on (or discontinue) my CFTR modulator during pregnancy?

- Can we review my med list and come up with a plan for what medications I need to change before and/or during pregnancy and what we’d do to treat a pulmonary exacerbation?

- How would my OB-GYN and/or Maternal Fetal Medicine (MFM) care be handled, and how would you communicate?

- If I’m interested in breastfeeding, do you have any information I should know? Do you recommend breastfeeding for me specifically?

- Can we talk about my risk and plan for postpartum depression?

- Can we set aside time to discuss my questions about pregnancy?

Click Here for additional questions for patient to ask their provider.

Preparing for Pregnancy

Pregnancy Risks and Complications

Pregnancy may have deleterious impacts on females with CF. To prevent harmful outcomes, women with CF and their clinicians should discuss some pre-pregnancy factors that can influence the decision to pursue pregnancy and have been reported to produce poor maternal health outcomes. These can include:

- Low ppFEV₁ (≤ 50%). Low FEV₁ has been shown to carry a higher risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

- Burkholderia cepacia: Women colonized with Burkholderia cepacia have shown declined lung function during pregnancy.

- Presence of pulmonary hypertension.

- Pancreatic insufficiency.

- CFRD (cystic fibrosis-related diabetes): Prior diagnosis with cystic fibrosis-related diabetes (CFRD) can cause fetal abnormalities if blood glucose levels are not controlled, so adequate glucose control before and during pregnancy should be a key focus for CF women and their clinical team.5,6

For females with these morbidities, conversations between prospective mothers and their clinicians regarding potential risks during pregnancy should also be discussed if other methods of becoming a parent are more appropriate.

Even without these predictors, we know that females with CF struggle to meet their nutritional and metabolic needs during the process of pregnancy. They experience a higher frequency of lung infections and hospitalizations. They also go to the doctor more frequently because of illness.6 Generally, fetal complications include low birth weight and pre-term delivery. Despite these challenges, there is positive data that live births among CF pregnancies are generally high, and CF disease among females with CF does not seem to worsen long-term because of pregnancy.6 Taylor-Cousar’s initial findings were generally encouraging regarding ETI and pregnancy.7

Health Status

The decision to build a family via pregnancy often requires that females with CF to consider factors such as fertility, current health status, the potential for complications, medication safety, fetal outcomes, and the prospect of managing parenthood with a chronic illness [see the Parenthood chapter in this guide for more information] [6-8].

Ultimately, the final decision to pursue pregnancy rests with the patient. However, three clinical parameters that can help ensure the best outcome for mother and baby include:

- Stable FEV1 of 50% or higher

- BMI 22 kg/m2 or higher

- Well-controlled blood sugar [9,10]

Among these factors, lung function may be the most important.[9] However, pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale (right-sided heart failure due to pulmonary disease) are considered contraindications to pregnancy, so consultation with a cardiologist may be needed to assess the patient.[10] Additionally, CF care teams may identify other specific risk factors for a given patient before determining whether pregnancy is advisable.

To fully assess the viability of a pregnancy, females considering pregnancy may need to consult with a variety of team members, from a dietician, social worker, pharmacist, and respiratory therapist to a mental health provider.

Suppose both provider and patient determine that pregnancy is not the best decision for her. In that case, there are other family-building options to consider, including surrogacy, adoption, fostering, or deciding not to have children [see Family Building chapter].

Medications

When planning for pregnancy, females with CF can work with their healthcare providers (e.g., CF care team, OB/GYN, complex pharmacist) to review their medications to determine the risks and benefits of each. Some females temporarily discontinue or change doses of particular oral and inhaled medications during pregnancy. Other medications may be placed on hold for specific trimesters or during breastfeeding. The Journal of Cystic Fibrosis provides a list of the most common CF medications and their safety profile for each trimester of pregnancy and during breastfeeding.[11]

Modulators, Pregnancy, and Breastfeeding

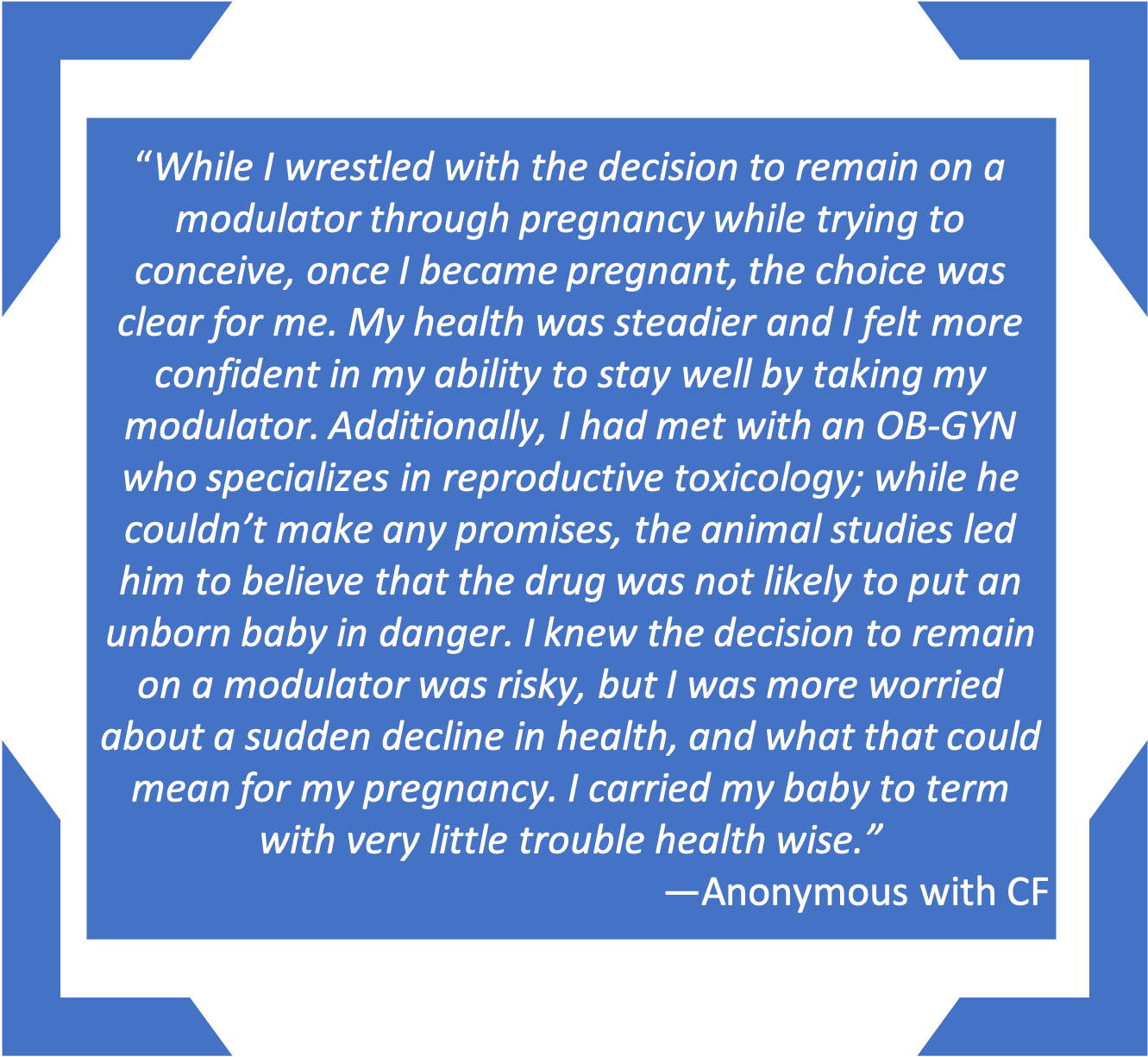

Patients are curious about the safety of taking HEMT during pregnancy and while breastfeeding. These concerns are pertinent because modulators are reportedly increasing planned, unexpected, or unplanned pregnancies within the CF female population [see the (In)Fertility chapter]. There is currently a study called MAYFLOWERS that comprehensively studies modulator safety issues during pregnancy.[12] Additional research in the US, UK, and Israel suggests that ivacaftor, lumacaftor, and tezacaftor are generally well-tolerated during pregnancy, with no reported related complications to the infants.[12,13] While some females have reportedly discontinued modulator use during pregnancy, they have experienced health declines and had to resume treatment later in pregnancy.

Genetic Counseling

CF is an autosomal recessive disorder, which means a person will only have CF if they inherit a faulty copy of the CFTR gene from each parent.[9] If a female with CF’s partner does not carry a CFTR gene mutation, her child will be a carrier but will not have CF. If her partner does carry a mutation, there is a 50% chance the child will have CF.[9] An excellent resource for CF genetic information is CFRT2.org.

More than 1,900 CFTR mutations exist, but some screenings only test for the most common mutations. Genomic sequencing is more comprehensive than common screenings. A provider may order it to provide heightened accuracy to their patient. When planning for pregnancy, a CF specialist can refer the patient to a genetic counselor to provide guidance. S/he/they can also order carrier testing for the patient’s partner. Females and their partners should ask their providers questions about any ordered tests concerning genetic and prenatal testing. They should also determine whether insurance will cover testing and include those expenses when calculating total pregnancy costs.

There is limited information on current views among females with CF about prenatal testing and genetic transmission of the disease. However, a University of Pittsburgh study called “Interviews to Understand Perspectives on Reproductive Genetic Counseling for People with Cystic Fibrosis” is underway.[14] In a systematic review by Gage et al., the authors cite two studies highlighting females’ concern about passing on CF genetic mutations. This consideration factored into their pregnancy decisions; knowing the risk of having a child with CF was a paramount concern. The studies cited, however, are either dated or have a very small sample size.[15]

Pregnancy and Transplant

Pregnancy after lung transplantation is considered a high-risk endeavor. Post-transplant, common risks of pregnancy to the mother include organ rejection, hypertension, renal complications, preeclampsia, and gestational diabetes due to immunosuppressive medications. Pregnancy post-transplant also carries an increased risk of miscarriage, preterm delivery, and low birth weight.[16] Experts recommend that post-transplant patients plan a pregnancy well in advance. The transplant team and a high-risk OB/GYN should also closely monitor the patient. The CF Foundation recommends that females with CF avoid getting pregnant for the first 2-3 years following transplant. Care teams often emphasize the importance of contraception and may recommend that patients use a long-acting reversible contraceptive method (LARC) throughout the transplant process.

During Pregnancy

Pregnant females with CF may be more likely than females without CF to experience certain symptoms and complications. Pregnancies in females with CF are often considered “high risk,” so care by a high risk OB/GYN or a maternal fetal medicine (MFM) specialist is recommended [8]. A female should work with her CF care team and her OB/GYN to determine a plan to monitoring plan. Together, the patient and her/their care teams may also discuss and confirm which CF medications or treatments may need to be altered during pregnancy, like certain antibiotics or types of vitamins, and the use of diagnostic treatments such as chest x-rays.

Like many pregnant females, those with CF may experience typical pregnancy symptoms (e.g., nausea and vomiting, fatigue, and shortness of breath). But there are also CF-specific concerns during pregnancy, which can include:

- Hemoptysis: Anecdotal evidence from the community, in addition to small studies, indicates that hemoptysis is a more frequent concern for females with CF during pregnancy than when they are not pregnant. Hormonal changes, increased blood volume (30-50% during pregnancy), and abnormal bronchial vessel development can cause hemoptysis.[17,18]

- Constipation: Many females experience constipation during pregnancy due to hormonal changes. In some cases, constipation is caused by increased iron in prenatal vitamins.[19] Females with CF who have a history of constipation or distal intestinal obstructive syndrome (DIOS) can experience pronounced constipation during pregnancy.[20] Constipation can be managed with stool softeners, laxatives, physical activity, and proper toilet positioning.

- Pulmonary Health: During pregnancy, the diaphragm rises about 4 centimeters, and the function residual capacity and residual volume of the lungs decreases by 15-20% at term. These changes may put an additional strain on the lung function of females with CF and can increase the risk of shortness of breath or pulmonary exacerbation during pregnancy.[18] Due to safety concerns over certain medications/antibiotics, females may have fewer or different options to treat a pulmonary exacerbation during pregnancy. Many females with CF are advised to adhere to a strict airway clearance routine and regular exercise throughout pregnancy.

- CFRD and Gestational Diabetes: Whether they have CFRD or not, females with CF are at an increased risk for developing gestational diabetes because they frequently cannot produce extra insulin to compensate for the insulin resistance that develops in pregnancy.[3,9] Pregnant females with CF with CFRD will likely need to undergo an oral glucose tolerance test earlier than the general population (between 12 and 16 weeks gestation, and then again closer to 24-28 weeks gestation).[21] Managing blood sugar during pregnancy is very important and may require a female to use insulin.

- Hypertension: Females with CF may be at an increased risk of hypertension during pregnancy, so they should monitor their blood pressure and discuss their results with their care teams.[22]

- Nutrition: Providers should monitor females with CF to ensure she has sufficient weight gain.

Other potential maternal complications in females with CF include infection, preterm labor, and gestational hypertension/preeclampsia. Some infant complications born to females with CF include increased rates of congenital anomalies, jaundice, C-sections, and premature (<37w) delivery.[1]

Pregnancy Loss & Pregnancy Termination

Rates of miscarriage in pre-transplant females with CF are either the same or very slightly elevated compared to the general population.[3] Females who have undergone lung transplants have a higher rate of miscarriage compared to non-transplanted individuals in the general population.[23] Miscarriage in females with CF may incur a heightened emotional impact because of existing mental health concerns related to chronic illness, fears about infertility, and familial or societal pressures to have children.

Approximately half of all pregnancies among females with CF are unplanned/unexpected; this rate may be increasing with the use of CFTR modulators.[24] When available, some females may choose termination of an unplanned pregnancy for personal reasons; others may terminate a planned pregnancy because of health concerns for the mother or fetus. In the first trimester, termination can be done with medications like mifepristone™ and misoprostol™ or by an office uterine aspiration procedure. A dilation and evacuation (D&E) procedure can be used if the pregnancy is more advanced. There are no universal guidelines for providers for when a pregnancy should be terminated due to CF health concerns. The rate of pregnancy termination cited in studies ranges from 0% to 20%, but females likely underreport terminations due to social stigma.[10]

Labor & Delivery

Given their medical histories, complex treatment regimens, and increased risk for pregnancy complications, females with CF may devote extra time and attention to plans related to labor, delivery, hospitalization, and packing their hospital bags! Creating a birth plan can help ease anxieties about labor and delivery. The plan could include CF-specific considerations to help doctors and nurses manage a female with CF’s labor (see Birth Plan Template below).

When giving birth at a hospital unaffiliated with a CF center, it may be helpful to become familiar with the facility before giving birth. Understanding how labor and delivery can be coordinated with CF team members is important. For example, some hospitals do not have access to CF-specific medications. If complications occur, the staff in these facilities may also need to be made aware of cross-infection protocols. It is, therefore, prudent for the female with CF to serve as a liaison between the birthing facility and the CF clinic.

While most females with CF have successful pregnancies and deliveries, both providers and patients should consider additional issues:

- Preterm delivery and/or cesarean section: Some females with CF are at greater risk for preterm delivery and/or cesarean section, particularly those whose FEV₁ is below 50-60%, whose health is unstable or whose diabetes is poorly controlled.[3,10] Overall, an estimated 10-25% of pregnant females with CF deliver early, either spontaneously or induced, due to declining maternal and/or fetal health.[18]

- Fetal growth: Babies of mothers with CF are at an increased risk for fetal growth restriction, particularly if the mother has low lung function or requires supplemental oxygen.[25] Females with CF should expect their OB/GYN to monitor the size and vitals of the baby closely, especially during the third trimester.

- Anesthesia: Anesthesia during labor can lead to complications for females with CF, especially for those with a lower baseline FEV₁.[20] OB/GYN or MFM providers may consult an obstetric anesthesiologist to help plan the patient’s labor and delivery, beginning in the second or third trimester. This consultation can allow the prospective mother with CF to understand any potential complications, assess the risks of anesthesia during labor, and formulate a birthing plan.

- Airway clearance: Airway clearance during and after labor can be complicated. Generally, it is best to mobilize and resume respiratory treatments as soon as possible. Which therapy can be performed and the timing of treatments will vary for each female based on the CF care team’s treatment plan. The patient should discuss airway clearance needs before delivery to maximize post-delivery lung function. Different facilities will have different therapy options; available modalities in the hospital may cause the mother to bring her medical equipment from home.

- Oxygen use: Oxygen use during labor and delivery is very common in females with severe pulmonary disease. Pain and anxiety during labor can lead to respiratory distress. Analgesics can help ease some of these symptoms. Bronchodilators, oxygen, or using a BiPAP machine, especially in prolonged labor, can also be helpful.[20] Pulmonary function status and the potential for pulmonary distress are factors that can contribute to the use of these adjunctives.

The Postpartum and the 4th Trimester

The 12 weeks following birth is often referred to as the 4th trimester. During this time, new mothers face physical and emotional challenges as they recover from delivery and adjust to life with a newborn.

Recovering from labor and delivery

Females with CF are typically encouraged to resume their regular treatment regimen as soon as possible following delivery. If a female has a c-section, she/they may need to adapt their approach to airway clearance and physical activity while recovering.

Females with CF tend to be prone to pelvic floor dysfunction; the pressure of a fetus during pregnancy and the process of labor and delivery may cause or exacerbate pelvic floor issues.[20,26] Physicians treating females with CF should work with their patients to proactively address symptoms and make referrals to physical therapy as needed [see Incontinence Chapter] for additional information about pelvic floor dysfunction.

Breastfeeding

With certain caveats, mothers with CF’s breastmilk are generally safe and healthy for their babies. CF-specific considerations may factor into a female’s decision on whether to breastfeed, for how long, and whether to supplement with formula:

- Nutrition: To maintain their weight, hydration, and milk supply while breastfeeding, mothers consume an extra 500 calories daily and 2 liters of fluids.[20,27] Some females with CF struggle to do this.

- Medications: Many medications are excreted into breast milk, and some may harm the baby’s health. The Maternal and Fetal Outcomes in the Era of Modulators (MAYFLOWERS) study contains a component designed to determine the concentration of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor (ETI) found in breastmilk to be able to help parents make more informed decisions about potential risks of breastfeeding while taking ETI.[12] Decisions about which medications are safe to continue may differ from those of pregnancy. A female can work with her/their CF team and consult apps like LactMed to determine the best course of action.

- Prioritizing treatments and rest: Breastfeeding is demanding, and some females with CF choose not to breastfeed because of that factor. Some supplement breastfeeding with formula to ensure they have the time and energy needed to maintain their health.

Social Support and Mental Health

Caring for a newborn can be exhausting. Because females with CF have demanding treatment regimens and face health challenges, they may find it difficult to get enough rest and establish a new routine with a newborn. Support from one’s partner, friends, and family members is crucial during this adjustment.

Some mothers with CF find that having a child has a positive impact on their treatment adherence. Others may experience the opposite, particularly during the newborn period [see the Parenthood chapter].

Postpartum depression is not well studied in females with CF, but data is currently being captured in the MAYFLOWERS study. Mental health screening and early intervention are important for maintaining a new mother’s mental health.

Monitoring and Maintaining Health

Depending on a female’s health status and any challenges experienced during pregnancy, a CF care team may want to monitor lung function, weight, and the patient’s overall health closely during the postpartum period. The care team should review and discuss postpartum contraception choices with the patient early in the pregnancy and no later than the third trimester. Given the challenges of pregnancy and caring for a newborn in females with CF, using contraception to avoid an unplanned pregnancy is advised. Many methods of birth control are safe to use during the postpartum period, even when breastfeeding [See the Contraception chapter].

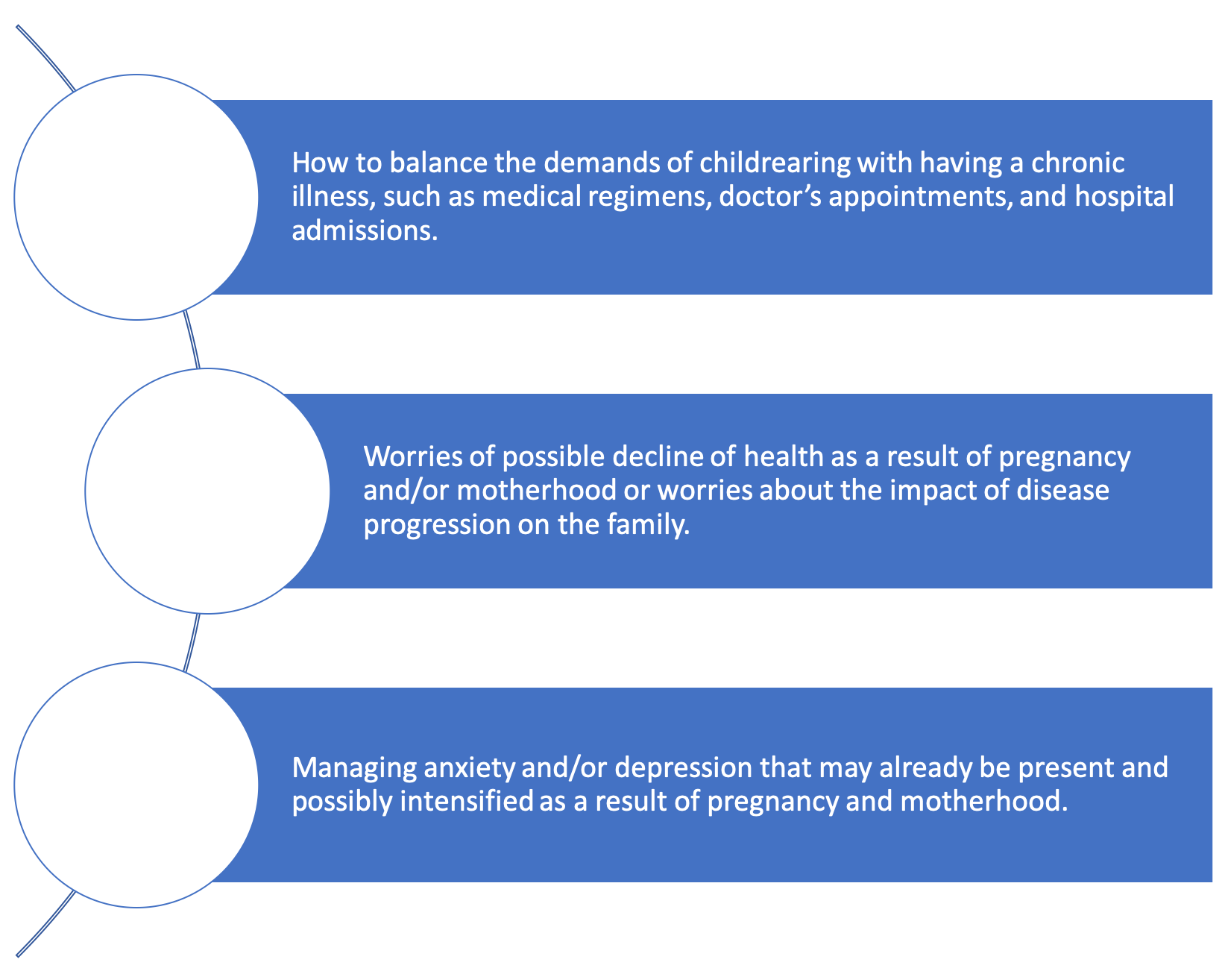

BPEmotional Health and Wellbeing Surrounding Pregnancy

Before, during, and after pregnancy, females with CF may face fears, anxieties, and unresolved questions. The decision to become pregnant and the impact of pregnancy and delivery can be challenging both physically and emotionally.

Discussing these feelings with one’s partner and the CF care team is important. It may be helpful to talk to a licensed therapist. In addition, various sources are available to females with CF; nonprofit organizations, local hospitals/CF clinics, and social media have numerous resources.

Mental Health Aspects of Modulator Therapy, Pregnancy, and Childbirth

Cystic Fibrosis (CF) patients have witnessed a transformation in their treatment landscape with the advent of HEMTs, like Trikafta (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor). These groundbreaking treatments have not only significantly enhanced the physical well-being of individuals with CF but have also paved the way for new opportunities and desirability in family-building, including parenthood and pregnancy.[28,29] However, it is essential to recognize that the use of CFTR modulators, while tremendously beneficial for many, has introduced a new dimension of consideration: the potential for neuropsychiatric adverse effects, as noted in a recent perspective piece by VanElzakker.[30]

Some of these neuropsychiatric adverse effects are mood disturbances, cognitive changes, increased anxiety, sleep disturbances, and even suicidal thoughts or behaviors. It is important to recognize that these symptoms can be so profound that some individuals with CF face the challenging decision of discontinuing a medication that could alleviate their physical suffering due to the severe side effects on their mental health.[29,30]

In addition to the possible mental health challenges related to taking Trikafta, pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period can also trigger mental health symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and mood disorders, with one in five women experiencing major depression during the perinatal period (from the beginning of pregnancy to one year after childbirth). Perinatal depression can have a significant impact on both the mother’s and child’s well-being and is one of the most common obstetric complications.[31,32]

It is important to note that pregnant women with CF, who may already be dealing with the demands of managing their condition, may be at an elevated risk for perinatal mental health issues, as chronic physical illness, particularly postpartum, can increase the risk of perinatal psychiatric symptoms.[28] Therefore, the mental health impact of these combined factors and experiences in pregnant women with CF cannot be overlooked.

Screening and Intervention

Given the potential for mental health challenges, screening for depression and anxiety is crucial during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Professional organizations recommend routine screening for perinatal depression and anxiety, utilizing tools such as the Edinburgh Depression Scale and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which are essential for identifying individuals at risk and ensuring timely interventions.[30,33]

Psychotherapy and social support are often the initial steps in addressing mild to moderate perinatal psychiatric symptoms, with cognitive-behavioral therapy being a well-established approach. Pharmacotherapy may be necessary in some cases, but careful consideration is required when determining medication options during preconception planning, pregnancy, and breastfeeding.[32–34]

At present, one approach to mitigating the neuropsychiatric adverse effects of CFTR modulators is off-label dose reduction. However, this approach has limitations, as minimal data informs the ideal dose reduction strategy and may come at the cost of reduced therapeutic effectiveness. While some individuals may find relief with dose reductions, others may still experience neuropsychiatric symptoms, necessitating comprehensive mental health support.[30,33]

Although studies on the mental health implications of family-building and pregnancy in CF are limited, ongoing research is essential better to understand the unique challenges and needs of this population. Research should focus on effective intervention strategies and support systems. Initiatives like the CF Foundation Mental Health Advisory Committee’s educational materials for CF parents can provide valuable resources. CF care teams are well-positioned to implement prevention and intervention strategies for individuals seeking to become parents.[29]

In conclusion, the combination of mental health issues and family-building considerations for individuals with CF taking HEMTs like Trikafta is a complex and critical area of concern. Addressing these challenges requires a multidisciplinary approach, including mental health screening, intervention, and ongoing research to provide comprehensive support for individuals navigating parenthood in the context of CF treatment.

Resources for Pregnancy, Postpartum, and Breastfeeding

Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health (https://womensmentalhealth.org)

Postpartum Support International (PSI) (https://postpartum.net/)

Common concerns identified by patient members of CFReSHC include:

“Having a strong support team has been essential for me. My husband and I share housework and childcare responsibilities equally. We also have family and friends nearby who we can rely on; they’ve helped watch kids, for example, while I have doctor’s appointments, when I’ve been admitted to the hospital, or when I’m not feeling well and need some rest. I also see a therapist to help me manage anxiety, depression, and other aspects of living with a chronic illness. Something one of my therapists told me that I’ll never forget is ‘you can’t serve from an empty vessel.’ It’s important to remember that caring for yourself is a crucial part of caring for your family; sharing tasks equally with your partner may not look like a 50/50 split on the outside. It’s important to discuss your expectations with your partner and openly communicate needs as they arise.”

Peer to Peer Advice

Patient members of CFReSHC offered the following peer-to-peer advice:

- As soon as you can, ideally, pre-pregnancy, find a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, and if possible, one familiar with CF.

- Talk to your doctor about the potential risks and benefits of stopping a modulator during pregnancy, especially since maternal health and pulmonary capacity are important to maintain.

- Consult with an OB/GYN who specializes in reproductive toxicology so you can better understand how different medications may impact a fetus.

- If you’re borderline CFRD, use a continuous glucose monitor as soon as you become pregnant or even before. Insurance may take a while to approve one, so getting one in advance can be helpful.

- Connect with another female with CF who has been through pregnancy via Facebook groups or the CF Foundation’s peer support program (CF Peer Connect).

- Take Miralax for constipation during pregnancy, and especially immediately postpartum, as many females become constipated after delivery.

- Know that staying on top of typical self-care can be hard during pregnancy and complicate CF treatments even more so.

- If you’re on oxygen, your O₂ needs may change during pregnancy.

- If approved by your medical team, keeping Tums at your bedside may be helpful to take as needed.

- If you deliver at a different hospital from where your CF care team admits, ensure your CF team communicates with your OB/GYN or MFM. Your CF care team should provide a written document detailing what kind of care you need and the appropriate medications for labor and delivery.

- Get a baby nurse or invite family or friends to help during the first couple of weeks postpartum.

- Work with a nutritionist on how to get enough calories, but healthily get those calories for yourself and your baby both during pregnancy and postpartum, especially if breastfeeding.

- Have birthing plans, but be flexible! Things can change quickly.

- Take your time and do research. Pregnancy with CF takes planning.

- Do not forget to plan for postpartum contraception while you are still pregnant so that you are prepared even before you give birth. Postpartum life will become much more hectic. It is best to discuss this with your CF care team and OB/GYN early in your pregnancy so that you can start contraception right after birth to avoid pregnancy that is too closely spaced. Often, physicians can provide birth control while you are in the hospital after labor and delivery.

Resource Links

- Medication databases such as Reprotox.org to check for drug safety

- CF Peer Connect Program coordinates one-to-one peer support for people with cystic fibrosis and their family members.

- Motherhood/Pregnancy Peer Support Group with Attain Health

- LactMed App

- CDC Contraception App [Android or Apple]

Works Cited

- Taylor-Cousar J. Sexual and Reproductive Health in the Era of Highly Effective Modulators. Presented at: CFReSHC Patient Task Force Meeting; January 24, 2023; Virtual. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eVnHyWl0xIQ&t=1s

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. CFF Patient Registry Annual Data Report 2022. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation; 2022. https://www.cff.org/medical-professionals/patient-registry

- Goddard J, Bourke SJ. Cystic fibrosis and pregnancy. Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;11(1):19-24. doi:10.1576/toag.11.1.19.27464

- Ahluwalia M, Hoag JB, Hadeh A, Ferrin M, Hadjiliadis D. Cystic fibrosis and pregnancy in the modern era: A case-control study. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13(1):69-73. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2013.08.004

- Goss CH, Rubenfeld GD, Otto K, Aitken ML. The Effect of Pregnancy on Survival in Women With Cystic Fibrosis. Chest. 2003;124(4):1460-1468. doi:10.1378/chest.124.4.1460

- Montemayor K, Franklin C, Dezube R, Lechtzin N, Sheffield J, West N. Maternal Outcomes in Pregnant Women with Cystic Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Published online 2019. doi:10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2019.199.1_meetingabstracts.a4331

- Schechter MS, Quittner AL, Konstan MW, Millar SJ, Pasta DJ, McMullen A. Long-term Effects of Pregnancy and Motherhood on Disease Outcomes of Women with Cystic Fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(3):213-219. doi:10.1513/annalsats.201211-108oc

- Burden C, Ion R, Chung Y, Henry A, Downey DG, Trinder J. Current pregnancy outcomes in women with cystic fibrosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;164(2):142-145. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.06.013

- Geake J, Tay G, Callaway L, Bell SC. Pregnancy and cystic fibrosis: Approach to contemporary management. Obstet Med. 2014;7(4):147-155. doi:10.1177/1753495X14554022

- Thorpe-Beeston J. Contraception and pregnancy in cystic fibrosis. J R Soc Med. 2009;102(1_suppl):3-10. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2009.s19002

- Kroon MAGM, Akkerman-Nijland AM, Rottier BL, Koppelman GH, Akkerman OW, Touw DJ. Drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women diagnosed with Cystic Fibrosis – An update. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17(1):17-25. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2017.11.009

- Jain R, Magaret A, Vu PT, et al. Prospectively evaluating maternal and fetal outcomes in the era of CFTR modulators: the MAYFLOWERS observational clinical trial study design. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2022;9(1). doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2022-001289

- Nash EF, Middleton PG, Taylor-Cousar JL. Outcomes of pregnancy in women with cystic fibrosis (CF) taking CFTR modulators – an international survey. J Cyst Fibros. 2020;19(4):521-526. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2020.02.018

- Kazmerski T, Rajinikanth G. Interviews to Understand Perspectives on Reproductive Genetic Counseling for People with Cystic Fibrosis. Ongoing study 2023.

- Gage LA. What Deficits in Sexual and Reproductive Health Knowledge Exist among Women with Cystic Fibrosis? A Systematic Review. Health Soc Work. 2012;37(1):29-36. doi:10.1093/hsw/hls003

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Pregnancy after transplant, pregnancy, and CF. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.cff.org/Life-With-CF/Transitions/Family-Planning-and-Parenting-With-CF/Pregnancy-and-CF/Pregnancy-After-Transplant/

- Renton M, Priestley L, Bennett L, Mackillop L, Chapman S. Pregnancy outcomes in cystic fibrosis: a 10-year experience from a UK centre. Obstet Med. 2015;8(2):99-101. doi:10.1177/1753495X15575628

- Sheffield J. CFReSHC Patient Task Force Meeting Presentation on Pregnancy in Women with CF. 2020. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1wcuVFYa-PGZjUOyb-f-aQ1Ps_FzZ21vI

- American Pregnancy Association. Constipation in pregnancy. Accessed November 8, 2023. https://americanpregnancy.org/pregnancy-health/constipation-during-pregnancy/

- Edenborough FP, Borgo G, Knoop C, et al. Guidelines for the management of pregnancy in women with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2008;7:S2-S32. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2007.10.001

- Moran A, Brunzell C, Cohen RC, et al. Clinical Care Guidelines for Cystic Fibrosis-Related Diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a clinical practice guideline of the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, endorsed by the Pediatric Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2697-2708. doi:10.2337/dc10-1768

- Jelin AC, Sharshiner R, Caughey AB. Maternal co-morbidities and neonatal outcomes associated with cystic fibrosis*. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(1):4-7. doi:10.3109/14767058.2016.1161747

- Shaner J, Coscia LA, Constantinescu S, et al. Pregnancy after Lung Transplant. Prog Transplant Aliso Viejo Calif. 2012;22(2):134-140. doi:10.7182/pit2012285

- Godfrey EM, Mody S, Schwartz MR, et al. Contraceptive use among women with cystic fibrosis: A pilot study linking reproductive health questions to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation National Patient Registry. Contracept Stoneham. 2020;101(6):420-426. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2020.02.006

- Grigoriadis C. Cystic Fibrosis and Pregnancy: Counseling, Obstetrical Management and Perinatal Outcome. Invest Clin. 2015;56(1):66-73. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25920187

- Neemuchwala F, Ahmed F, Nasr SZ. Prevalence of Pelvic Incontinence in Patients With Cystic Fibrosis. Glob Pediatr Health. 2017;4:2333794X17743424. doi:10.1177/2333794X17743424

- Centers for Disease Control. Maternal diet-breastfeeding. Published 2020. Accessed June 25, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/diet-and-micronutrients/maternal-diet.html

- Taylor-Cousar J. CFTR Modulators: Impact on Fertility, Pregnancy, and Lactation in Women with Cystic Fibrosis. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):2706. doi:10.3390/jcm9092706

- Kazmerski TM, West NE, Jain R, et al. Family‐building and parenting considerations for people with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2021;57(S1):S75-S88. doi:10.1002/ppul.25620

- VanElzakker MB, Tillman EM, Yonker LM, Ratai EM, Georgiopoulos AM. Neuropsychiatric adverse effects from CFTR modulators deserve a serious research effort. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2023;29(6):603-609. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000001014

- Leng LL, Yin XC, Ng SM. Mindfulness-based intervention for clinical and subthreshold perinatal depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Compr Psychiatry. 2023;122:152375-152375. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2023.152375

- Woody CA, Ferrari AJ, Siskind DJ, Whiteford HA, Harris MG. A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;219:86-92. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.003

- Talwalkar JS, Koff JL, Lee HB, Britto CJ, Mulenos AM, Georgiopoulos AM. Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Regulator Modulators: Implications for the Management of Depression and Anxiety in Cystic Fibrosis. Psychosom Wash DC. 2017;58(4):343-354. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2017.04.001

- Cuijpers P, Franco P, Ciharova M, et al. Psychological treatment of perinatal depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2023;53(6):2596-2608. doi:10.1017/S0033291721004529

Free Printable PDF Download

Want a free printable PDF download of this section for your use in clinic? Just give us your name and email address below to get your download link. This will not add you to our email list.